John Crawfurd

John Crawfurd FRS (13 August 1783 – 11 May 1868) was a Scottish physician, colonial administrator, diplomat, and author who served as the second and last Resident of Singapore.

He was born on Islay, in Argyll, Scotland, the son of Samuel Crawfurd, a physician, and Margaret Campbell; and was educated at the school in Bowmore.

The Sultan was encouraged by Pakubuwono IV of Surakarta to assume he had support in resisting the British; who sided with his opponents: his son, the Crown Prince, and Pangeran Natsukusuma.

[8] Java was returned to the Dutch in 1816, and Crawfurd went back to England that year, shortly becoming a Fellow of the Royal Society, and turning to writing.

21 November 1821, the mission embarked on the John Adam for the complicated and difficult navigation of the Hoogly river, taking seven days to sail the 140 miles (225 km.)

British claim to the island was based upon payment of a quit-rent accordant with European feudal law, which Crawfurd feared the Siamese would challenge.

Pointedly questioned in this regard in an urgent private meeting with the Prah-klang (Prayurawongse), the reply was, "that if the Siamese were at peace with the friends and neighbours of the British nation, they would certainly be permitted to purchase fire-arms and ammunition at our ports, but not otherwise."

He was under orders to reduce the expenditure on the existing factory there, but instead responded to local commercial representations, and spent money on reclamation work on the river.

[15] He also concluded the final agreement between the East India Company, and Sultan Hussein Shah of Johor with the Temenggong, on the status of Singapore on 2 August 1824.

[19] He edited and contributed to the Singapore Chronicle of Francis James Bernard, the first local newspaper that initially appeared dated 1 January 1824.

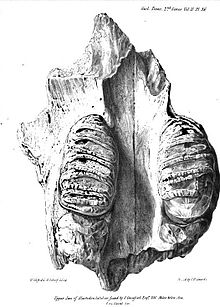

Back in London, William Clift identified a new species of mastodon (more accurately Stegolophodon) from them;[25] Hugh Falconer also worked on the collection.

[26] The finds, of fossil bones and wood, were discussed further in a paper by William Buckland, giving details;[27] and they brought Crawfurd the friendship of Roderick Murchison, Foreign Secretary of the Geological Society.

[31] He joined the Parliamentary Candidate Society, founded by Thomas Erskine Perry (his brother-in-law), to promote "fit and proper" Members of Parliament.

[40] In Preston in the 1837 general election Crawfurd had the Liberal nomination in a three-cornered fight for two seats, as Peter Hesketh-Fleetwood was regarded as a waverer by the Conservatives who ran Robert Townley Parker against him; but he polled third.

[43] A lifelong advocate of free trade policies, in A View of the Present State and Future Prospects of the Free Trade and Colonization of India (1829), Crawfurd made an extended case against the East India Company's approach, in particular in excluding British entrepreneurs, and in failing to develop Indian cotton.

Crawfurd's part as parliamentary agent for interests in Calcutta had been paid (at £1500 per year); his publicity work had included facts for an Edinburgh Review article written by another author.

[52] In 1843 Crawfurd gave evidence to the Colonial Office on Port Essington, on the north coast of Australia, to the effect that its climate made it unsuitable for settlement.

In 1855 Crawfurd went with a delegation to the Board of Control of the East India Company, with representations on behalf of the Straits dollar as an independent currency.

Crawfurd lobbied in both Houses of Parliament, with George Keppel, 6th Earl of Albemarle acting to bring a petition to the Lords, and William Ewart Gladstone putting the case in the Commons.

Among the arguments put was that the dollar was a decimal currency, while the rupee used by traders, and legal tender in East India Company territories since it was coined in 1835, was not.

His views have been seen as inconsistent: a recent author wrote that "[...] Crawfurd seemed to embody a complex mixture of elements of coexisting but ultimately contradictory value systems".

[69] A harsh critic of the existing Calcutta agencies, he noted the absence of bill broking in India and suggested that an exchange bank should be set up.

[70] His view that an economy dominated by agriculture was inevitably an absolute government was cited by Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in his On the Constitution of the Church and State.

Crawfurd held polygenist views, based on multiple origins of human groups; and these earned him, according to Sir John Bowring, the nickname "the inventor of forty Adams".

[73] He expressed these views to the Ethnological Society of London (ESL), a traditional stronghold of monogenism (belief in a unified origin of humankind) where he had come in 1861 to hold office as President.

[75] Crawfurd wrote in 1861 in the Transactions of the ESL a paper On the Conditions Which Favour, Retard, and Obstruct the Early Civilization of Man, in which he argued for deficiencies in the science and technology of Asia.

analyses have sought to clarify Crawfurd's agenda in his writings on race and, at this time, when he had become prominent in a young and still fluid field and discipline.

[citation needed] Trosper has taken Ellingson's analysis a step further, attributing to Crawfurd a conscious "spin" put on the idea of primitive culture, a rhetorically sophisticated use of a "straw man" fallacy, achieved by bringing in, irrelevantly but for the sake of incongruity, the figure of Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

[83] Right at the end of his life, in 1868, Crawfurd was using a "missing link" argument against Sir John Lubbock, in what Ellingson describes as a misrepresentation of a Darwinist viewpoint based on the idea that a precursor of humans must still be extant.

[94] Thomas Carlyle met Henry Crabb Robinson at dinner at the Crawfurds (25 November 1837, at 27 Wilton Crescent), making a poor impression.