John Crerar (industrialist)

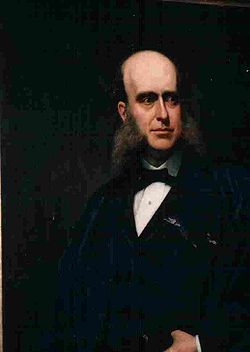

John Crerar (8 March 1827 – 19 October 1889) was a wealthy American industrialist and businessman from Chicago whose investments were primarily in the railroad industry.

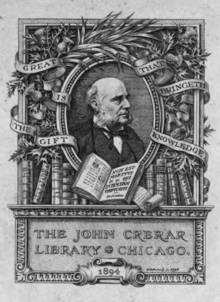

Although he had a successful business career he is most well known for his philanthropic efforts, his activism in the Presbyterian Church, and his investment in the John Crerar Library.

He joined a rival large iron firm, working there until the age of 29, always vigilant for a viable escape into an independent business life.

Crerar's luck changed when he met Morris K. Jesup, two years his junior, but already having established in 1853 a railroad supply company.

In that year they first advertised themselves as "Crerar, Adams & Co., manufacturers and dealers in railroad supplies and contractors' materials, 11 and 13 Wells Street."

This location was destroyed by the 1871 fire, situating itself temporarily in a "mere shanty" and then at the Robbins Building, where it would continue until Crerar's death.

When the company was founded in 1867, Crerar was an incorporator and a member of the board of directors, in which capacity he would serve for twenty-two years.

In his will Crerar left Blackstone, although a man of great wealth, a bequest of $5,000, "to purchase some memento which will remind him of my appreciation and his uniform and life-long kindness to me."

Other directorships included that of the London and Globe Insurance Company, the Illinois Trust and Savings Bank and the Chicago and Joliet Railroad.

In New York, he dedicated his energy to the Scottish Presbyterian Church which had nurtured his family during their difficult early years in the city.

Despite his growing business concerns, he attended church regularly, constantly reading the Bible, his favourite chapter of which was Romans 8, which he knew by heart.

Although generally a quiet man, religious skepticism was known to raise his ire, and he was often blunt in defending his beloved faith and church.

As president of the Mercantile Library Association of New York, he was instrumental in bringing William Makepeace Thackeray, author of Vanity Fair, to America on a lecture tour.

I desire that the books and periodicals be selected with a view to create and sustain a healthy moral and Christian sentiment in the community and that all nastiness and immorality be excluded.

I want its atmosphere that of Christian refinement, and its aim and object the building up of character, and I rest content that the friends I have named will carry out my wishes in those particulars.

Later it was loaned by the Chicago Parks Commissioners to the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, and viewed by millions of visitors in San Francisco in 1915.

Magruder, speaking before the Chicago Literary Club, said, "With a modesty that bespeaks the greatness of his soul, he orders a simple headstone to be placed at his own grave, but that a colossal statue be raised to the man who abolished slavery in the United States.

The millionaire is content to lie low, but he insists that the great emancipator shall rise high…This contrast between the headstone and the statue indicates, as plainly as though it had been expressed in words, Mr. Crerar's estimate of true heroism.

His doctor, Dr. Frank Billings, accompanied him to Atlantic City, New Jersey, the climate of which was thought to have been good for his health, but on 9 September, he suffered a partial stroke of paralysis on his right side.

Full of fun and anecdotes, he dearly loved a good story.He expressed a desire in his will to be buried beside his mother, the central figure in his life, from which he had inherited his religious and social zeal, and who had predeceased him in 1873.

After John's death, litigation arose over his will as distant relatives, mostly resident in North Easthope, near Stratford, Ontario, Canada, read of their exclusion from the bequests.