John Edgar Wideman

In addition to his work as a writer, Wideman has had a career in academia as a literature and creative writing professor at both public and Ivy League universities.

According to Wideman family lore, this ancestor first settled the area that eventually became the Pittsburgh neighborhood of Homewood, despite the fact that a white lawyer and politician, William Wilkins, is credited with founding the community.

[6] Wideman's paternal grandfather moved to Pittsburgh as part of the Great Migration of the early 20th century, when many African Americans fled Southern states.

During World War II, Wideman's father enlisted in the U.S. Army and was stationed in Charleston, South Carolina, and on Saipan.

[8] With the support of Edgar's earnings, the family was able to move to Shadyside, a predominantly white neighborhood, allowing Wideman to attend Peabody High School.

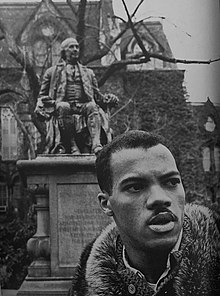

[11] Wideman attended the University of Pennsylvania, where he was offered a Benjamin Franklin Scholarship for academic merit and was one of a small number of African Americans to enroll in 1959.

To get ahead, to make something of myself, college had seemed a logical, necessary step; my exile, my flight from home began with good grades, with good English, with setting myself apart long before I'd earned a scholarship and a train ticket over the mountains to Philadelphia... if I ever had any hesitations or reconsiderations about the path I'd chosen, youall were back home in the ghetto to remind me how lucky I was.

[19] For his academic achievements, which included winning campus-wide awards for both creative and scholarly writing, Wideman was inducted into the Phi Beta Kappa national honor society.

[20] In 1963, before graduating with a bachelor's degree in English, Wideman was named a Rhodes Scholar, becoming the second African American to win the prestigious award from the University of Oxford.

[23][24] In 1965, Wideman married Judith Goldman, a white Jewish woman from Long Island whom he began dating when both were undergraduates at Penn.

A reviewer for The New York Times admired the novel's "dazzling display" of "Joycean" prose and Wideman's "formidable command of the techniques of fiction".

Examining violent strains of black nationalist ideology that had emerged during the 1960s, the novel depicts African-American characters who plan to lynch a white police officer.

Writing in The New York Times, Anatole Broyard claimed that Wideman "can make an ordinary scene sing the blues like nobody's business", although he found the novel to be flawed.

[30] In 1974, Wideman was promoted to a full professorship of English at Penn, and he received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to pursue research in African-American literature.

The circumstances of her birth were traumatic, as a complication caused Wideman's wife, Judith, to be transported by ambulance from Laramie, Wyoming, to Denver, Colorado, where Jamila was born two months premature.

In November 1975, along with two accomplices, he participated in a robbery scheme that went awry when the intended victim, a fence named Nicola Morena, fled.

The victim's family later filed a lawsuit against the city of Pittsburgh, the hospitals and doctors involved, and the ambulance drivers, claiming negligence.

That suit was not successful, although the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania acknowledged that a delay in Morena's treatment was "a contributing factor in causing his death".

[34] Robert and his accomplices fled Pittsburgh and arrived in Laramie, where Wideman let them spend a night in his house, an act he has attributed to naïveté.

After an eight-year publication hiatus, he published two books simultaneously: a story collection, Damballah, and a novel, Hiding Place, both of which appeared in 1981 and allude to the events that resulted in Robert's imprisonment.

The trilogy was celebrated upon publication, inspiring a claim in The New York Times that Wideman was "one of America's premier writers of fiction".

[41] Writing in The New York Review of Books in 1997, Joyce Carol Oates claimed that it belongs among the "masterpieces of American memoir".

[44] A plea bargain was then struck, in which Jacob pleaded guilty to first-degree murder and was sentenced to life in prison, with a possibility of parole after 25 years.

[45] A year after the murder, Wideman wrote a letter to the Kane family, forgiving them for wanting the death penalty for Jacob, and they responded angrily.

Inspired by the police's 1985 bombing of the Philadelphia headquarters of the black liberation group known as MOVE—an act that resulted in the death of five children and the loss of two city blocks[47]—the "intense, poetic narrative"[48] centers on one man's attempt to find, and write about, a child rumored to have survived the tragedy.

[52] He edited anthologies, provided introductions for books, and appeared in various media, including television, to comment on societal issues, particularly those affecting African Americans.

The scholar Heather Russell explains that, in focusing on this concept, Wideman's writing "reflects African American traditions of storytelling within which myth, history, parable, parody, folklore, fact, and fiction exist in synergy.

The scholar Tracie Church Guzzio summarizes Wideman's approach to trauma when she claims that his writing "illustrates that the trauma suffered by African Americans in the period of slavery in America is re-lived and re-experienced in the continuing racism confronting African Americans in their daily lives as well as in the images projected by history, literature, and popular culture".

[38] However, scholars and critics have pointed to figures that, judging from Wideman's work and interviews, appear to be literary or intellectual influences.

In 1993, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, in awarding him a fellowship, noted that Wideman "has contributed to a new humanist perspective in American literature, distilling personality and history, crime and mysticism, art and the exigencies of material life into his work.