John Fogge

Sir John Fogge (c. 1417–1490) was an English courtier, soldier and supporter of the Woodville family under Edward IV who became an opponent of Richard III.

However, Rosemary Horrox argues that he was the son of another John Fogge, Sir William’s younger brother, and Jane Cotton.

[4] John Fogge was born about 1417 and it seems certain that he was the grandson of Sir Thomas Fogge—as he was eventually the recipient of his inheritance—[4](d. 13 July 1407[5]) and Joan de Valence (d. 8 July 1420),[6] widow of William Costede of Costede, Kent, and daughter of Sir Stephen de Valence of Repton.

Gillian Draper writes:John Fogge, the grandson of Sir Thomas, was probably born in 1417, and was ordained to the first tonsure in Canterbury Cathedral in 1425.

[11]According to Horrox, Fogge had reached the age of majority by 1438, but only came to prominence when he inherited the lands of the senior line on the death of Sir Thomas's grandson and heir, William by February 1447.

[citation needed] Despite his earlier service under Henry VI, when the future Edward IV landed in England in June 1460, Fogge joined the Yorkists, and was granted Tonford in Thanington and Dane Court in Boughton under Blean, manors to which he claimed to be entitled by reversion.

[4] After the Yorkist victory at the Battle of Towton on 29 March 1461, 'Fogge emerged as a leading royal associate in Kent, heading all commissions named in the county'.

In 1461, he was granted the office of Keeper of the Writs of the Court of Common Pleas,[12] and took part in the investigation of the possible treason of Sir Thomas Cooke, Lord Mayor of London.

[citation needed] According to Horrox, his name is not found in commissions during the Readeption of Henry VI, suggesting the possibility that he went into exile with Edward IV.

[15][4] During this period Fogge built close ties to the Prince of Wales,[4] and from 1473 was a member of his council and administrator of his property.

[28][29] Alice de Criol or Kyriell died between February 1462 when she was amongst those endowing two chaplains to pray her father and others slain at Northampton, St. Albans and Shirebum,[30] and 9 May 1462.

[31] They had a son and heir, John Fogge married secondly, between February 1462 (when his first wife was alive)[30] and 9 May 1462,[31] Alice Haute or Hawte (born c.1444), the daughter of William Haute, Esquire, MP (d.1462[31]) of Bishopsbourne, Kent,[42] and Joan Woodville, daughter of Richard Woodville.

[22] The official biographers of Katherine Parr, Susan E. James and Linda Porter, state that Joan was the granddaughter of Fogge.

Joan might have been of about the same age as the three daughters mentioned in Sir John Fogge's will who were all unmarried and left sums towards their dowries and to the 'Governance and Guiding' of his wife Alice.

His sentimental bequests were all reserved for his two surviving sons and his wife Alice, though Gillian Draper leaves room for the possibility that he intended for a mass book to pass to one of his daughters:Sir John Fogge had a private chapel at the manor house of Repton as well as the Fogge chapel in Ashford church.

Alice was to keep all of these for her whole life and most of them – apart from the velvet vestment and the mass book – were then to pass to Fogge’s son John or his heirs with the intention that they should remain for the use of the chapel at Repton.

The velvet vestment could have been considered a personal item with which Alice may have had some involvement, say in its embroidery, or something she might convert for her own wear, and thus unsuitable to pass on.

Eastern Kent, where the Fogges lived and held lands and manors, was an area of extensive literacy mainly because of the proximity of the Cinque Ports with their early traditions of civic record-keeping.

The clerk was to ring the new Great Bell of the church in the tower which Fogge had caused to be built, and six wax tapers were to be lighted, presumably on the high altar.

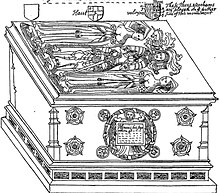

This was immediately adjacent to Fogge’s tomb and just to the east of the choir with its sixteen stalls with their misericords, where presumably the master and the others sang.

When the Great Bell was rung, it would draw the attention of the townspeople and the town’s poor: after their attendance at the obit a meal of southern beef, bread and ale was to be provided for thirteen of them, plus a penny each in cash.