John II of France

When he came to power, France faced several disasters: the Black Death, which killed between a third and a half of its population; popular revolts known as Jacqueries; free companies (Grandes Compagnies) of routiers who plundered the country; and English aggression that resulted in catastrophic military losses, including the Battle of Poitiers of 1356, in which John was captured.

In an exchange of hostages, which included his son Louis I, Duke of Anjou, John was released from captivity to raise funds for his ransom.

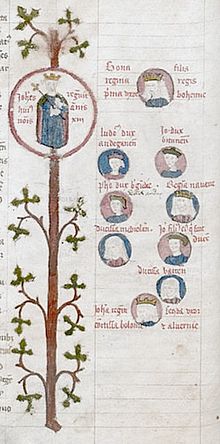

Philip selected Bonne of Bohemia as a wife for his son, as she was closer to child-bearing age (16 years), and the dowry was fixed at 120,000 florins.

John reached the age of majority, 13 years and one day, on 27 April 1332, and received the Duchy of Normandy, as well as the counties of Anjou and Maine.

Therefore, Norman members of the nobility were governed as interdependent clans, which allowed them to obtain and maintain charters guaranteeing the duchy a measure of autonomy.

King Philip, worried about the richest area of the kingdom breaking into bloodshed, ordered the bailiffs of Bayeux and Cotentin to quell the dispute.

Geoffroy d'Harcourt raised troops against the king, rallying a number of nobles protective of their autonomy and against royal interference.

[5] Clement VI was the fourth of seven Avignon Popes whose papacy was not contested, although the supreme pontiffs would ultimately return to Rome in 1378.

By 1345, increasing numbers of Norman rebels had begun to pay homage to Edward III, constituting a major threat to the legitimacy of the Valois kings.

Duke John met Geoffroy d'Harcourt, to whom the king agreed to return all confiscated goods, even appointing him sovereign captain in Normandy.

To escape the pandemic, John, who was living in the Parisian royal residence, the Palais de la Cité, left Paris.

On 9 February 1350, five months after the death of his first wife, John married Joan I, Countess of Auvergne, in the royal Château de Sainte-Gemme (which no longer exists), at Feucherolles, near Saint-Germain-en-Laye.

[7] In November 1350, King John had Raoul II of Brienne, Count of Eu seized and summarily executed,[8] for reasons that remain unclear, although it was rumoured that he had pledged the English the County of Guînes for his release from captivity.

[9] In 1354, John's son-in-law and cousin, Charles II of Navarre, who, in addition to his Kingdom of Navarre in the Pyrenees mountains, bordering between France and Spain, also held extensive lands in Normandy, was implicated in the assassination of the Constable of France, Charles de la Cerda, who was the favorite of King John.

The following year, on 10 September 1355 John and Charles signed the Treaty of Valognes, but this second peace lasted hardly any longer than the first, culminating in a highly dramatic event where, during a banquet on 5 April 1356 at the Royal Castle in Rouen attended by the King's son Charles, Charles II of Navarre, and a number of Norman magnates and notables of the French king burst through the door in full armor, swords in hand, along with his entourage, which included the king's brother Phillip, younger son Louis and cousins, as well as over a hundred fully armed knights waiting outside.

"[10] He then ordered the arrests of all the guests including Navarre and, in what many considered to be a rash move as well as a political mistake, he had John, the Count of Harcourt and several other Norman lords and notables summarily executed later that night in a yard nearby while he stood watching.

[11] This act, which was largely driven by revenge for Charles of Navarre's and John of Harcourt's pre-meditated plot that killed John's favorite, Charles de La Cerda, would push much of what remaining support the King had from the lords in Normandy away to King Edward and the English camp, setting the stage for the English invasion and the resulting Battle of Poitiers in the months to come.

On 30 June 1360 John left the Tower of London and proceeded to Eltham Palace where Queen Philippa had prepared a great farewell entertainment.

[14] Leaving his son Louis of Anjou in Calais as a replacement hostage to guarantee payment, John was allowed to return to France to raise the funds.

Troubled by the dishonour of this action, and the arrears in his ransom, John gathered his royal council to announce that he would voluntarily return to captivity in England and negotiate with Edward in person.

[citation needed] The image of a "warrior king" probably emerged from the courage he displayed at the Battle of Poitiers, where he dismounted to fight in the forefront of his surrounded men with a poleaxe in his hands,[21] as well as the creation of the Order of the Star.

This was guided by political need, as John was determined to prove the legitimacy of his crown, particularly as his reign, like that of his father, was marked by continuing disputes over the Valois claim from both Charles II of Navarre and Edward III of England.

[citation needed] From a young age, John was called to resist the decentralising forces affecting the cities and the nobility, each attracted either by English economic influence or the reforming party.