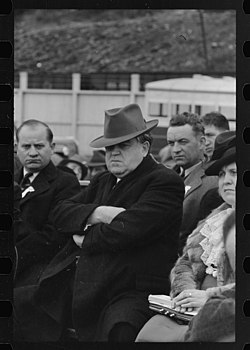

John L. Lewis

John Llewellyn Lewis (February 12, 1880 – June 11, 1969) was an American leader of organized labor who served as president of the United Mine Workers of America (UMW) from 1920 to 1960.

Lewis was a Republican but played a major role in helping Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt win a landslide victory for the US presidency in 1936.

Lewis was an effective, aggressive fighter and strike leader who gained high wages for his membership while steamrolling over his opponents, including the United States government.

Lewis was one of the most controversial and innovative leaders in the history of labor, gaining credit for building the industrial unions of the CIO into a political and economic powerhouse to rival the AFL.

His massive leonine head, forest-like eyebrows, firmly set jaw, powerful voice, and ever-present scowl thrilled his supporters, angered his enemies, and delighted cartoonists.

[4] Lewis attended three years of high school in Des Moines and at the age of 17 went to work in the Big Hill Mine at Lucas.

President Woodrow Wilson obtained an injunction, which Lewis obeyed, telling the rank and file, "We cannot fight the Government."

[citation needed] Coal miners worldwide were sympathetic to socialism, and in the 1920s, Communists systematically tried to seize control of UMWA locals.

[6] He placed the once-autonomous districts under centralized receivership, packed the union bureaucracy with men directly beholden to him, and used UMWA conventions and publications to discredit his critics.

In Southern Illinois, amidst widespread violence, the Progressive Mine Workers of America challenged Lewis but were beaten back.

[9] In 1924, Lewis a Republican,[10] framed a plan for a three-year contract between the UMWA and the coal operators, providing for a pay rate of $7.50 per day ($133 in 2023 dollars).

Lewis helped secure passage of the Guffey Coal Act of 1935, which raised prices and wages, but it was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court.

At the AFL's annual convention in 1934, Lewis gained an endorsement from them of the principle of industrial unionism, as opposed to limitations to skilled workers.

In early 1937, his CIO affiliates won collective-bargaining contracts with two of the most powerful anti-union corporations, General Motors and United States Steel.

General Motors surrendered as a result of the great Flint Sit-Down Strike, during which Lewis negotiated with company executives, Governor Frank Murphy of Michigan, and President Roosevelt.

[14] The CIO gained enormous strength and prestige from the victories in automobiles and steel and escalated its organizing drives, targeting industries that the AFL had long claimed, especially meatpacking, textiles, and electrical products.

Some cite his frustration over FDR's response to the General Motors and "Little Steel" strikes of 1937, or the President's purported rejection of Lewis' proposal to join him on the 1940 Democratic ticket.

Reuben Soderstrom, President of the Illinois State Federation of Labor, ripped his former ally apart in the press, saying he had become "the most imaginative, the most efficient, the most experienced truth-twisting windbag that this nation has yet produced.

Prior to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Lewis was staunchly opposed to American entry into World War II.

In August 1941 he joined Herbert Hoover, Alfred Landon, Charles Dawes, and other prominent conservatives in their appeal to Congress to halt President Roosevelt's "step-by-step projection of the United States into undeclared war.

Six months later, he substantively violated organized labor's no-strike pledge, spurring President Roosevelt to seize the mines.

[27] After briefly affiliating with the AFL, Lewis broke with them again over signing non-Communist oaths required by the 1947 Taft–Hartley Act, making the UMW independent.

Lewis, never a Communist, still refused on principle to allow any of his officials to take the non-Communist oath required by the Taft–Hartley Act; the UMW was therefore denied legal rights protected by the National Labor Relations Board.

[30] In the 1950s, Lewis won periodic wage and benefit increases for miners and led the campaign for the first Federal Mine Safety Act in 1952.

Lewis tried to impose some order on a declining industry through collective bargaining, and maintaining standards for his members by insisting that small operators agree to contract terms that effectively put many of them out of business.

It ended the practice where the UMWA had kept a number of its districts in trusteeship for decades, meaning that Lewis appointed union officers who otherwise would have been elected by the membership.

"He was my personal friend," wrote Reuben Soderstrom, the President of the Illinois AFL-CIO, who had once lambasted Lewis as an "imaginative windbag," upon news of his death.