John Leverett

[4] By the early 1630s Leverett's father was an alderman in Boston, and had acquired, in partnership with John Beauchamp of the Plymouth Council for New England, a grant now known as the Waldo Patent for land in what is now the state of Maine.

[16] He would pursue the idea politically, often in the face of opposition from the conservative Puritan leadership of Massachusetts that opposed religious views that did not accord with their own.

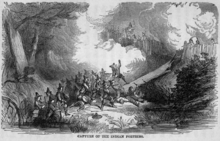

In 1642 Leverett and Edward Hutchinson were sent as diplomatic envoys to negotiate with the Narragansett chief Miantonomoh amid concerns that all of the local Indian tribes were conspiring to wage war on the English colonists.

Governor John Endecott in 1652 sent a survey party to determine the colony's northern boundary, which was specified by the charter to be 3 miles (4.8 km) north of the Merrimack River.

[25] Endecott sent Leverett as one of several commissioners to negotiate the inclusion of these settlements into the colonial government, which resulted in the eventual formation of York County, Massachusetts.

Word of this arrived in the New World in 1652,[32] and rumors flew around the English colonies of New England that the Dutch in New Amsterdam were conspiring with all of the region's Indians to make war against them.

[33] Leverett and Robert Sedgwick both saw a significant benefit for their trading operations if the Dutch could be eliminated as competitors, and lobbied for military action against New Amsterdam, although religious moderates like Simon Bradstreet were opposed to it.

[36] Cromwell responded by giving Sedgwick a commission as military commander of the New England coast, and sent him and Leverett with several ships and some troops to make war on the Dutch.

Sedgwick took advantage of his commission to act instead against the French in neighboring Acadia, which was home to privateers who preyed on English shipping.

[38] During this time he and Sedgwick enforced a virtual trade monopoly on French Acadia for their benefit, leading some in the colony to view Leverett as a predatory opportunist.

[38] From 1663 to 1673, Leverett held the rank of major-general of the Massachusetts militia,[41] and was repeatedly elected as a deputy to the general court or to the council of assistants.

[43] The arrival of the commissioners was of some concern to the government, and Leverett was placed on a committee to draft a petition to the king demanding the commission's recall.

The document they drafted characterized the commissioners as "agents of evil sent to Massachusetts to subvert its charter and destroy its independence.

[45] His tenure as governor was chiefly notable because of King Philip's War, and the rising threats to the colonial charter that culminated in its revocation in 1684.

The colony angered the king by purchasing the claims of Sir Ferdinando Gorges to portions of Maine in 1677, a territory Charles had intended to acquire for his son, the Duke of Monmouth.

Baptists were able to openly begin worship in Boston during his tenure, but he has also been criticized by Quaker historians for harsh anti-Quaker laws passed in 1677.

[50] Leverett died in office, reportedly from complications of kidney stones, on 16 March 1678/9, and was interred at the King's Chapel Burying Ground in Boston.

[51][52] His descendants include his grandson John, the seventh President of Harvard College, and Leverett Saltonstall, a 20th-century governor of Massachusetts.

[54] Cotton Mather wrote of Leverett that he was "one to whom the affections of the freemen were signalised his quick advances through the lesser stages of honor and office, unto the highest in the country; and one whose courage had been as much recommended by martial actions abroad in his younger years, as his wisdom and justice were now at home in his elder.