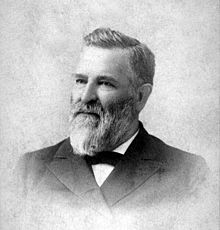

John Mullan (road builder)

Leaving the United States Army in April 1863, he failed at several businesses before profiting immensely as a real estate dealer and land attorney in California.

He attended St. John's College in Annapolis, where he studied Greek, Latin, history, mathematics, philosophy, art, rhetoric, navigation, surveying, chemistry, and geology, among other subjects.

[3] Probably due to his father's lengthy career in the Army, John Mullan Jr. sought admission to the United States Military Academy at West Point, New York.

[13] Few cadets engaged in extracurricular reading at the West Point library, but Mullan checked out large quantities of books, many of them dealing with the newly acquired western United States.

[16] On November 4, 1852, Mullan left New York City aboard a steamship, traversed the Isthmus of Nicaragua, and arrived in San Francisco on December 1, 1852,[17] where he was assigned to the 1st Artillery Regiment.

This would force Congress to survey and fund the construction of a southern route, which in turn would lead to rapid development of the area and the creation of new slave-holding states (as permitted under the Missouri Compromise).

[23] Stevens largely had his pick of men for the survey project, and chose a wide range of common soldiers, laborers, topographers, engineers, doctors, naturalists, astronomers, geologists, and meteorologists.

Stevens originally intended for Donelson and Mullan to lead a party north along the Big Muddy to its headwaters (near modern Plentywood, Montana) before heading west along the border with Canada before turning south to reach Fort Benton[49]—the highest navigable point on the Missouri River.

[71] Returning to the Missoula Valley, from November 28 to December 13 he retraced his route to the Big Hole River, followed it south to its headwaters, then crossed the Beaverhead Mountains to enter modern-day Idaho.

Obtaining soldiers, wagons, and supplies, he departed on March 14 and scouted out a level prairie road from Fort Benton to the confluence of the Sun and Missouri rivers (at present-day Great Falls, Montana).

[88] A day later they met Michael Ogden, a Hudson's Bay Company agent who had established a temporary trading post in the vicinity of modern-day Kalispell, Montana.

Meanwhile, Mullan and the remainder of his group traveled northwest about 30 miles (48 km) to Fort Colville, a Hudson's Bay Company trading post located at Kettle Falls on the Columbia River.

[112] Convinced that Native American attacks and additional settlement of the area could be achieved only by having a military road built, Isaac Stevens resigned as Washington Territory's governor and was elected its congressional delegate in July 1857.

Gen. Newman S. Clarke, commander of the Department of the Pacific, ordered Wright to not only punish the tribes severely but to make any surrender conditional: Mullan must be allowed to build his road without being molested in the slightest.

[149] Mullan had requested permission in June to travel to Washington, D.C., to confer with the War Department and members of Congress so that additional funds might be procured for the military road.

On September 30, a messenger reached Wright's column with orders directing Mullan to proceed to Fort Vancouver near the mouth of the Columbia River and await instructions.

In late December 1858 or early January 1859, Jefferson Davis drafted an amendment to the bill, approving $350,000 for a military road from Fort Abercrombie (on the North Dakota–Minnesota border) to Seattle.

[157] Mullan and Kolecki spent most of March gathering information on road-building from other military officers and civilians who had done so out west; ordering equipment; sending out orders for a larger civilian work crew, including several more highly educated and trained men like Kolecki and Sohon; asking the military for an escort for his work crew; and seeking funds so he could obtain gifts for Native Americans.

[160] He now hired more than 80 civilians as his road construction crew, including his own brothers Louis (a drover) and Charles (a physician), and his future brother-in-law, David Williamson.

Mullan also acquired 180 oxen and dozens of cattle, horses, and mules, and hired famed wagon master John Creighton to organize his pack train.

[171] Having cut the road through roughly 80 miles (130 km) of forest and mountains, Mullan's crew called a halt near modern-day De Borgia, Montana, and constructed residential huts, a log cabin office, and a storehouse.

His excellent relations with this tribe convinced 17 Kalispel to take 120 horses and accompany Gustav Sohon across the mountains to Fort Benton, and return laden with the supplies which the War Department had shipped there via steamboat.

[194] He immediately wrote to Captain Humphreys, informing him that the southern route around Lake Pend Oreille was the incorrect one, and asking for funds and permission to reroute the Mullan Road around the north end.

[201] With the American Civil War on the verge of breaking out, and Mullan's patron Jefferson Davis having defected to the Confederacy, there was little desire in the Army to spend money on a road in the Washington Territory.

[210] Lt. Charles G. Harker from Fort Colville arrived with more men,[212] and Mullan's civilians and soldiers began cutting through dense timber north of Lake Coeur d'Alene on June 5.

[219] On August 13, Mullan dispatched Lt. Marsh with 50 soldiers and civilians to lightly repair the road ahead, with an eye to moving supplies into the Bitterroot Valley for the winter camp.

With Bidwell contributing some used stagecoaches, in August 1865 Mullan led the first group to travel along the newly improved road, arriving in Ruby City (about 40 miles (64 km) southwest of Boise) on September 1.

[279] Mullan, who had spent a great deal of time in the past five years in the national capital working on his land business, now proposed to represent California in Washington, D.C., to secure these missing funds.

In 1886, however, former California Surveyor General Robert Gardner initiated a campaign to discredit Mullan, accusing him of hiding the true size of the potential federal payment in order to enrich himself.

[336][ab] Despite his ill health, Mullan continued to earn money doing limited legal work, primarily for miners and farmers suing the United States Department of the Interior and for the Catholic Church.