John Russell, 1st Earl Russell

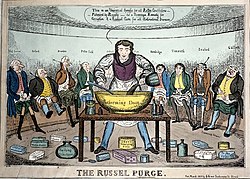

[2] He favoured expanding the right to vote to the middle classes and enfranchising Britain's growing industrial towns and cities, but he never advocated universal suffrage and he opposed the secret ballot.

The future reformer gained his seat by virtue of his father, the Duke of Bedford, instructing the 30 or so electors of Tavistock to return him as an MP even though at the time Russell was abroad and under age.

He further traveled in Eastern Europe even when Parliament reassembled, and on the Christmas Eve of that year, Russell was able to enjoy a memorable interview with the recently exiled Emperor of the French Napoleon Bonaparte.

In June 1815, Russell denounced the Bourbon Restoration and Britain's declaration of war against the recently returned Napoleon by arguing in the House of Commons that foreign powers had no right to dictate France's form of government.

In 1828, while still an opposition backbencher, Russell introduced a Sacramental Test bill with the aim of abolishing the prohibitions on Catholics and Protestant dissenters being elected to local government and from holding civil and military offices.

In November 1845, following the failure of that year's potato harvest across Britain and Ireland, Russell came out in favour of the repeal of the Corn Laws and called upon the Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel to take urgent action to alleviate the emerging food crisis.

On 11 December 1845, frustrated by his party's unwillingness to support him on repeal, Peel resigned as prime minister and Queen Victoria invited Russell to form a new government.

[39] Russell took office as prime minister with the Whigs only a minority in the House of Commons and particularly during a time of national crisis, facing "famine, fever, trade failing, and discontent growing", as described in his wife's journal on 14 July.

At the general election of August 1847 the Whigs made gains at the expense of the Conservatives, but remained a minority, with Russell's government still dependent on the votes of Peelite and Irish Repealer MPs to win divisions in the Commons.

I cannot indeed claim the merit either of having carried measures of Free Trade as a Minister, or of having so prepared the public mind by any exertions of mine as to convert what would have been an impracticable attempt into a certain victory.

But I have endeavoured to do my part in this great work according to my means and convictions, first by proposing a temperate relaxation of the Corn Laws, and afterwards, when that measure has been repeatedly rejected, by declaring in favour of total repeal, and using every influence I could exert to prevent a renewal of the struggle for an object not worth the cost of conflict.

Great social improvements are required; public education is manifestly imperfect; the treatment of criminals is a problem yet undecided; the sanitaiy condition of our towns and villages has been grossly neglected.

[44] In the aftermath of the political and social turmoil that took place during the Revolutions of 1848, fears grew of a similar outcome in Britain particularly in Ireland which led to the passage of the Treason Felony Act 1848 that made it illegal and punishable by penal labour speaking or writing against the Crown.

[46][47] The act was influenced by the work of Sir Edwin Chadwick and Dr. Thomas Southwood Smith, addressed the pressing sanitary issues in cities and towns, leading to improvements in public health and the general social conditions of the population.

"[53] In January 1847, the government abandoned this policy, realising that it had failed, and turned to a mixture of "indoor" and "outdoor" direct relief; the former administered in workhouses through the Irish Poor Laws, the latter through soup kitchens.

[55][56][57] In 1838, representatives of the working class amplified calls for reform in the People's Charter of 1838 which demanded universal manhood suffrage, equal division of constituencies, vote by ballots and abolishing the qualification of owning property in order to sit in Parliament.

For my own part, I saw in these proceedings a fresh proof that the people of England were satisfied with the Government under which they had the happiness to live, did not wish to be instructed by their neighbours in the principles of freedom, and did not envy them either the liberty they had enjoyed under Robespierre, or the order which had been established among them by Napoleon the Great.

Russell, therefore, proposed that the British delegation should exert diplomatic pressure on Vienna to relinquish Lombardy and Venice, thereby averting further escalation and preserving the balance of power in Europe.

Unlike Russell, who sought to avoid open conflict and maintain stability through diplomacy, Palmerston was more willing to take bold if not rash action, even if they risked alienating allies or provoking international disputes.

In a letter to his brother, he reflected on the political turbulence of the past months and on winning the success he deserves by writing: "After the trumpetings of attacks that were to demolish first one and then another of the Government: first me, then Grey, then Charles Wood; we have come triumphantly out of the debates and divisions, and end the session stronger than we began it.

On 4 November 1850, in a letter to the Bishop of Durham published in The Times the same day, Russell wrote that the Pope's actions suggested a "pretension to supremacy" and declared that "No foreign prince or potentate will be permitted to fasten his fetters upon a nation which has so long and so nobly vindicated its right to freedom of opinion, civil, political, and religious".

[72] Louis Philippe's flight from Paris signalled a new spark of revolutionary fervour throughout Europe and next went to Austria, where a student revolt forced Austrian Chancellor Count Metternich out of the country and take up refuge in England with Emperor Ferdinand considering asylum in Tyrol.

As the leader of the largest party in the coalition, Russell was reluctant to serve under Aberdeen in a subordinate position, but agreed to take on the role of Foreign Secretary on a temporary basis, to lend stability to the fledgling government.

Together with Palmerston, Russell supported the government taking a hard line against Russian territorial ambitions in the Ottoman Empire, a policy that ultimately resulted in Britain's entry into the Crimean War in March 1854, an outcome that the more cautious Aberdeen had hoped to avoid.

In January 1855, after a series of military setbacks, a Commons motion was brought by the radical MP John Roebuck to appoint a select committee to investigate the management of the war.

In February 1858 the Government rushed through a Conspiracy to Murder bill, following the attempted assassination of Napoleon III by Italian nationalist Felice Orsini – an attack planned in Britain using British-made explosives.

His tenure of the Foreign Office was noteworthy for the famous dispatch in which he defended Italian unification: "Her Majesty's Government will turn their eyes rather to the gratifying prospect of a people building up the edifice of their liberties, and consolidating the work of their independence, amid the sympathies and good wishes of Europe" (27 October 1860).

His second premiership was short and frustrating, and Russell failed in his great ambition of expanding the franchise, a task that would be left to his Conservative successors, Derby and Benjamin Disraeli.

His great achievements, wrote A. J. P. Taylor, were based on his persistent battles in Parliament over the years on behalf of the expansion of liberty; after each loss he tried again and again, until finally, his efforts were largely successful.

His published works include: A Tale of Two Cities by Charles Dickens was dedicated to Lord John Russell, "In remembrance of many public services and private kindnesses.