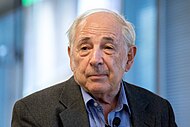

John Searle

[8] Searle's early work on speech acts, influenced by J. L. Austin and Ludwig Wittgenstein, helped establish his reputation.

In 1959, Searle began teaching at Berkeley, and he was the first tenured professor to join the 1964–65 Free Speech Movement.

Both rely heavily on insinuation and innuendo, and both display a hatred --one might almost say terror-- of close analysis and dissection of argument."

"[10] In the late 1980s, Searle, along with other landlords, petitioned Berkeley's rental board to raise the limits on how much he could charge tenants under the city's 1980 rent-stabilization ordinance.

"[15] The court described the debate as a "morass of political invective, ad hominem attack, and policy argument".

Finally, he alluded to the long-term nature of the conflict and blamed the attacks on the lack of American resolve to deal forcefully with America's enemies over the past several decades.

The Los Angeles Times reported: "A new lawsuit alleges that university officials failed to properly respond to complaints that John Searle ... sexually assaulted his ... research associate last July and cut her pay when she rejected his advances.

"[18][19] The case brought to light several earlier complaints against Searle, on which Berkeley allegedly had failed to act.

[22] After news of the lawsuit became public, several previous allegations of sexual harassment and assault by Searle were also revealed.

[23] On June 19, 2019, following campus disciplinary proceedings by Berkeley's Office for the Prevention of Harassment and Discrimination (OPHD), University of California President Janet Napolitano approved a recommendation that Searle have his emeritus status revoked, after a determination that he had violated university policies against sexual harassment and retaliation between July and September 2016.

[24] According to a later account, which Searle presents in Intentionality (1983) and which differs in important ways from the one suggested in Speech Acts, illocutionary acts are characterised by having "conditions of satisfaction", an idea adopted from Strawson's 1971 paper "Meaning and Truth", and a "direction of fit", an idea adopted from Austin and Elizabeth Anscombe.

Collections of articles referring to Searle's account are found in Burkhardt 1990[27] and Lepore / van Gulick 1991.

(Searle is at pains to emphasize that 'intentionality', the capacity of mental states to be about worldly objects, is not to be confused with 'intensionality', the referential opacity of contexts that fail tests for 'extensionality'.

[29]) For Searle, intentionality is exclusively mental, being the power of minds to represent or symbolize over, things, properties and states of affairs in the external world.

[30] Causal covariance, about-ness and the like are not enough: maps, for instance, only have a 'derived' intentionality, a mere after-image of the real thing.

Beginning with the possibility of reversing these two, an endless series of sceptical, anti-real or science-fiction interpretations could be imagined.

[35] To have a Background is to have a set of brain structures that generate appropriate intentional states (if the fire alarm does go off, say).

"[36] It seems to Searle that Hume and Nietzsche were probably the first philosophers to appreciate, respectively, the centrality and radical contingency of the Background.

He argues that, starting with behaviorism, an early but influential scientific view, succeeded by many later accounts that Searle also dismisses, much of modern philosophy has tried to deny the existence of consciousness, with little success.

Searle says simply that both are true: consciousness is a real subjective experience, caused by the physical processes of the brain.

Searle has argued[43] that critics like Daniel Dennett,[44] who he claims insist that discussing subjectivity is unscientific because science presupposes objectivity, are making a category error.

In other words, the latter statement is evaluable, in fact, falsifiable, by an understood ('background') criterion for mountain height, like "the summit is so many meters above sea level".

[48][49] Douglas Hofstadter and Daniel Dennett in their book The Mind's I criticize Searle's view of AI, particularly the Chinese room argument.

[50] Stevan Harnad argues that Searle's "Strong AI" is really just another name for functionalism and computationalism, and that these positions are the real targets of his critique.

Aiming at an explanation of social phenomena in terms of Anscombe's notion, he argues that society can be explained in terms of institutional facts, and institutional facts arise out of collective intentionality through constitutive rules with the logical form "X counts as Y in C".

[55] In recent years, Searle's main interlocutor on issues of social ontology has been Tony Lawson.

Lawson emphasizes the notion of social totality whereas Searle prefers to refer to institutional facts.

Similarly, every time a smoker who feels guilty about their action lights a cigarette, they are aware that they are succumbing to their craving, and not merely acting automatically as they do when they exhale.

Furthermore, he believes that this provides a desire-independent reason for an action – if one orders a drink at a bar, there is an obligation to pay for it even if one has no desire to do so.

[62] Third, Searle argues that much of rational deliberation involves adjusting patterns of desires, which are often inconsistent, to decide between outcomes, not the other way around.