John Smith (explorer)

This is an accepted version of this page John Smith (baptized 6 January 1580 – 21 June 1631) was an English soldier, explorer, colonial governor, admiral of New England, and author.

Following his return to England from a life as a soldier of fortune and as a slave,[1] he played an important role in the establishment of the colony at Jamestown, Virginia, the first permanent English settlement in North America, in the early 17th century.

[3] Harsh weather, a lack of food and water, the surrounding swampy wilderness, and attacks from Native Americans almost destroyed the colony.

He claimed descent from the ancient Smith family of Cuerdley, Lancashire,[6] and was educated at King Edward VI Grammar School, Louth, from 1592 to 1595.

He served as a mercenary in the army of Henry IV of France against the Spaniards, fighting for Dutch independence from King Philip II of Spain.

[10] Smith reputedly killed and beheaded three Ottoman challengers in single-combat duels, for which he was knighted by the Prince of Transylvania and given a horse and a coat of arms showing three Turks' heads.

[1] He was sent as an enslaved gift to a woman in Constantinople (Istanbul), Charatza Tragabigzanda, who sent him to perform agricultural work and to be converted to Islam in Rostov.

However, they landed at Cape Henry on 26 April 1607 and unsealed orders from the Virginia Company designating Smith as one of the leaders of the new colony, thus sparing him from the gallows.

The Company wanted Smith to pay for Newport's voyage with pitch, tar, sawed boards, soap ashes, and glass.

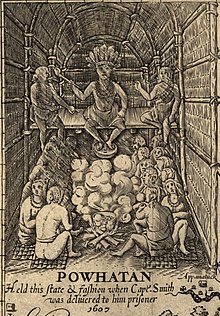

Absent interpreters or any other means of effectively interviewing the Englishman, Opechancanough summoned his seven highest-ranking kwiocosuk, or shamans, and convened an elaborate, three-day divining ritual to determine whether Smith's intentions were friendly.

Finding it a good time to leave camp, Opechancanough took Smith and went in search of his brother, at one point visiting the Rappahannock tribe who had been attacked by a European ship captain a few years earlier.

[26] The time gap in publishing his story raises the possibility that Smith may have exaggerated or invented the event to enhance Pocahontas' image.

He said that Smith's recounting of the story of Pocahontas had been progressively embellished, made up of "falsehoods of an effrontery seldom equaled in modern times".

[28] Some have suggested that Smith believed that he had been rescued, when he had in fact been involved in a ritual intended to symbolize his death and rebirth as a member of the tribe.

[31] Smith told a similar story in True Travels (1630) of having been rescued by the intervention of a young girl after being captured in 1602 by Turks in Hungary.

[34] In the summer of 1608, Smith left Jamestown to explore the Chesapeake Bay region and search for badly needed food, covering an estimated 3,000 miles (4,800 km).

In his absence, Smith left his friend Matthew Scrivener as governor in his place, a young gentleman adventurer from Sibton Suffolk who was related by marriage to the Wingfield family, but he was not capable of leading the people.

Argall also brought news that the Virginia Company of London was being reorganized and was sending more supplies and settlers to Jamestown, along with Lord De la Warr to become the new governor.

One sank in a storm soon after leaving the harbour, and the Sea Venture wrecked on the Bermuda Islands with flotilla admiral Sir George Somers aboard.

They finally made their way to Jamestown in May 1610 after building the Deliverance and Patience to take most of the passengers and crew of the Sea Venture off Bermuda, with the new governor Thomas Gates on board.

[37] The commercial purpose was to take whales for fins and oil and to seek out mines of gold or copper, but both of these proved impractical so the voyage turned to collecting fish and furs to defray the expense.

[38] Most of the crew spent their time fishing, while Smith and eight others took a small boat on a coasting expedition during which he traded rifles for 11,000 beaver skins and 100 each of martins and otters.

The expedition's second vessel under the command of Thomas Hunt stayed behind and captured a number of Indians as slaves,[39] including Squanto of the Patuxet.

[48] The Captain John Smith Monument currently lies in disrepair off the coast of New Hampshire on Star Island, part of the Isles of Shoals.

The pillar featured three carved faces, representing the severed heads of three Turks that Smith lopped off in combat during his stint as a soldier in Transylvania.

[53][54] Many critics judge Smith's character and credibility as an author based solely on his description of Pocahontas saving his life from the hand of Powhatan.

Lemay claims that many promotional writers sugar-coated their depictions of America in order to heighten its appeal, but he argues that Smith was not one to exaggerate the facts.

[60] "Therefore, he presented in his writings actual industries that could yield significant capital within the New World: fishing, farming, shipbuilding, and fur trading".

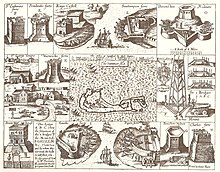

As Lemay remarks, "maps tamed the unknown, reduced it to civilisation and harnessed it for Western consciousness," promoting Smith's central theme of encouraging the settlement of America.

[63] Many "naysayers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century" have made the argument that Smith's maps were not reliable because he "lacked a formal education in cartography".