John Tyndall

Later he made discoveries in the realms of infrared radiation and the physical properties of air, proving the connection between atmospheric CO2 and what is now known as the greenhouse effect in 1859.

Tyndall also published more than a dozen science books which brought state-of-the-art 19th century experimental physics to a wide audience.

In the decade of the 1840s, a railway-building boom was in progress, and Tyndall's land surveying experience was valuable and in demand by the railway companies.

Recalling this decision later, he wrote: "the desire to grow intellectually did not forsake me; and, when railway work slackened, I accepted in 1847 a post as master in Queenwood College.

"[6] Another recently arrived young teacher at Queenwood was Edward Frankland, who had previously worked as a chemical laboratory assistant for the British Geological Survey.

The pair moved to Germany in summer 1848 and enrolled at the University of Marburg, attracted by the reputation of Robert Bunsen as a teacher.

In his search for a suitable research appointment, he was able to ask the longtime editor of the leading German physics journal (Poggendorff) and other prominent men to write testimonials on his behalf.

In the spring of 1859, Tyndall began research into how thermal radiation, both visible and obscure, affects different gases and aerosols.

On 26 May he gave the Royal Society a note which described his methods, and stated "With the exception of the celebrated memoir of M. Pouillet on Solar Radiation through the atmosphere, nothing, so far as I am aware, has been published on the transmission of radiant heat through gaseous bodies.

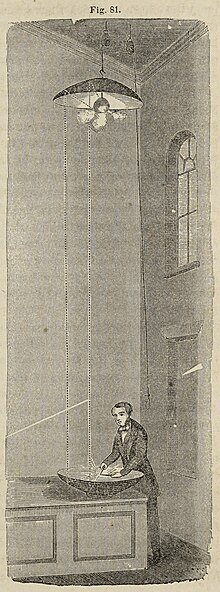

[39] In his lectures at the Royal Institution Tyndall put a great value on, and was talented at producing, lively, visible demonstrations of physics concepts.

Tyndall said in 1879: "During nine years of labour on the subject of radiation [in the 1860s], heat and light were handled throughout by me, not as ends, but as instruments by the aid of which the mind might perchance lay hold upon the ultimate particles of matter.

When a plate of rock-salt is heated via conduction and let stand on an insulator, it takes an exceptionally long time to cool down; i.e., it's a poor emitter of infrared.)

As an indicator of his teaching attitude, here are his concluding remarks to the reader at the end of a 200-page tutorial book for a "youthful audience", The Forms of Water (1872): "Here, my friend, our labours close.

In the sweat of our brows we have often reached the heights where our work lay, but you have been steadfast and industrious throughout, using in all possible cases your own muscles instead of relying upon mine.

"[55] As another indicator, here is the opening paragraph of his 350-page tutorial entitled Sound (1867): "In the following pages I have tried to render the science of acoustics interesting to all intelligent persons, including those who do not possess any special scientific culture.

[56] His first published tutorial, which was about glaciers (1860), similarly states: "The work is written with a desire to interest intelligent persons who may not possess any special scientific culture."

Its primary feature is, as James Clerk Maxwell said in 1871, "the doctrines of the science [of heat] are forcibly impressed on the mind by well-chosen illustrative experiments.

"[58] Tyndall's three longest tutorials, namely Heat (1863), Sound (1867), and Light (1873), represented state-of-the-art experimental physics at the time they were written.

Much of their contents were recent major innovations in the understanding of their respective subjects, which Tyndall was the first writer to present to a wider audience.

Mathematical modelling using infinitesimal calculus, especially differential equations, was a component of the state-of-the-art understanding of heat, light and sound at the time.

The majority of the progressive and innovative British physicists of Tyndall's generation were conservative and orthodox on matters of religion.

Tyndall, however, was a member of a club that vocally supported Charles Darwin's theory of evolution and sought to strengthen the barrier, or separation, between religion and science.

Though not nearly so prominent as Huxley in controversy over philosophical problems, Tyndall played his part in communicating to the educated public what he thought were the virtues of having a clear separation between science (knowledge & rationality) and religion (faith & spirituality).

The newspapers carried the report of it on their front pages – in Britain, Ireland & North America, even the European Continent – and many critiques of it appeared soon after.

The attention and scrutiny increased the friends of the evolutionists' philosophical position, and brought it closer to mainstream ascendancy.

Even in Italy, Huxley and Darwin were awarded honorary medals and most of the Italian governing class was hostile to the papacy.

[64] He tried unsuccessfully to get the UK's premier scientific society to denounce the Irish Home Rule proposal as contrary to the interests of science.

[citation needed] Tyndall became financially well-off from sales of his popular books and fees from his lectures (but there is no evidence that he owned commercial patents).

His successful lecture tour of the United States in 1872 netted him a substantial amount of dollars, all of which he promptly donated to a trustee for fostering science in America.

John Tyndall is commemorated by a memorial (the Tyndalldenkmal) erected at an elevation of 2,340 metres (7,680 ft) on the mountain slopes above the village of Belalp, where he had his holiday home, and in sight of the Aletsch Glacier, which he had studied.