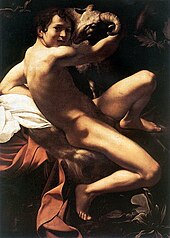

John the Baptist (Caravaggio)

He lived in the wilderness of Judea between Jerusalem and the Dead Sea, "his raiment of camel's hair, and a leather girdle about his loins; and his meat was locusts and wild honey."

Perez Sanchez's view that while the figure of the saint has certain affinities with Cavarozzi's style, the rest of the picture does not, "and the extremely high quality of certain passages, especially the beautifully depicted vine leaves...is much more characteristic of Caravaggio."

[2] Peter Robb, taking the painting to be by Caravaggio, dates it to about 1598, when the artist was a member of the household of his first patron, Cardinal Francesco Maria Del Monte.

The leaves behind the figure, and the plants and soil around his feet, are depicted with that careful, almost photographic sense of detail which is seen in the contemporary still life Basket of Fruit, while the melancholy self-absorption of the Baptist creates an atmosphere of introspection.

There's almost nothing to signify that this indeed the prophet sent to make straight the road in the wilderness – no cross, no leather belt, just a scrap of camel's skin lost in the voluminous folds of the red cloak, and the ram.

The ram itself is highly un-canonical – John the Baptist's animal is supposed to be a lamb, marking his greeting of Christ as the 'Lamb of God' come to take away the sins of mankind.

The role of these gigantic male nudes in Michelango's depiction of the world before the Laws of Moses has always been unclear – some have supposed them to be angels, others that they represent the Neo-Platonic ideal of human beauty – but for Caravaggio to pose his adolescent assistant as one of the Master's dignified witnesses to the Creation was clearly a kind of in-joke for the cognoscenti.

Ciriaco Mattei's notebook records two payments to Caravaggio in July and December of that year, marking the beginning and completion of the original John the Baptist.

In 1604 Caravaggio was commissioned to paint a John the Baptist for the papal banker and art patron Ottavio Costa, who already owned the artist's Judith Beheading Holofernes and Martha and Mary Magdalene.

Stark contrasts of light and dark accentuate the perception that the figure leans forward, out of the deep shadows of the background and into the lighter realm of the viewer's own space...The brooding melancholy of the Nelson-Atkins Baptist has attracted the attention of almost every commentator.

It seems, indeed, as if Caravaggio instilled in this image an element of the essential pessimism of the Baptist's preaching, of the senseless tragedy of his early martyrdom, and perhaps even some measure of the artist's own troubled psyche.

The saint's gravity is at least partly explained, too, by the painting's function as the focal point of the meeting place of a confraternity whose mission was to care for the sick and dying and to bury the corpses of plague victims.

[5]Caravaggio biographer Peter Robb has pointed out that the fourth Baptist seems like a psychic mirror-image of the first, with all the signs reversed: the brilliant morning light which bathed the earlier painting has become harsh and almost lunar in its contrasts, and the vivid green foliage has turned to dry dead brown.

Artists from Giotto to Bellini and beyond had shown the Baptist as an approachable story, a symbol understandable to all; the very idea that a work should express a private world, rather than a common religious and social experience, was radically new.

Caravaggio was not the first artist to have treated the Baptist as a cryptic male nude - there were prior examples from Leonardo, Raphael, Andrea del Sarto and others – but he introduced a new note of realism and drama.

His John has the roughened, sunburnt hands and neck of a labourer, his pale torso emerging with a contrast that reminds the viewer that this is a real boy who has gotten undressed for his modelling session – unlike Raphael's Baptist, who is as idealised and un-individualised as one of his winged cherubs.

[6] John Gash treats it as by Caravaggio, pointing out the similarity in the treatment of the flesh to the Sleeping Cupid, recognised as by the artist and dating from his Malta period.

His recognised works from this period include such masterpieces as the Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt and his Page and The Beheading of Saint John the Baptist.

The boy is immersed in a reverie: perhaps as Saint John he is lost in private melancholy, contemplating the coming sacrifice of Christ; or perhaps as a real-life street-kid called on to model for hours he is merely bored.

The red cloak envelopes his puny childish body like a flame in the dark, the sole touch of colour apart from the pale flesh of the juvenile saint.

"Compared with the earlier Capitolina and Kansas City versions...the Borghese picture is more richly colouristic - an expressive essay in reds, whites, and golden browns.

It also represents a less idealised and more sensuous approach to the male nude, as prefigured in the stout-limbed figures of certain of Caravaggio's post-Roman works, such as the Naples Flagellation and the Valletta Beheading of John the Baptist".

[2] Borghese was a discriminating collector but notorious for extorting and even stealing pieces that caught his eye – he, or rather his uncle Pope Paul V, had recently imprisoned Giuseppe Cesari, one of the best-known and most successful painters in Rome, on trumped-up charges in order to confiscate his collection of a hundred and six paintings, which included three of the Caravaggios today displayed in the Galleria Borghese (Boy Peeling Fruit, Young Sick Bacchus, and Boy with a basket of Fruit).

Through the steps hereditary within the family went to Don Pedro Antonio, tenth Earl of Lemos, who was appointed viceroy of Peru in 1667 and was certainly responsible for the transfer of St. John lying in Latin America.

After being in a private collection of El Salvador and then to Buenos Aires, the painting was brought in Bavaria following a lady of Argentina, just before the Second World War (Marini 2001, p. 574).

28–45), in written communications from Stroughton (1987), Pico Cellini (1987), Pepper (1987), Spike ( 1988), Slatkes (1992) and Claudio Strinati (1997), but it should be noted also that Bologna (1992, p. 342) considered the work a copy of a lost original by the Neapolitan church of Sant'Anna dei Lombardi .

This painting can not be confused with any other of St. John of Merisi, who have an origin and a commission documented; therefore its connection with the mentioned in the letters of Deodato Gentile to Scipione Borghese is certainly to be welcomed.

In the languid pose of St. John are discernible Venetian memories: the reference is specifically to the Venuses and Danae of Giorgione and Titian, but also to the ancient representations of river gods and paintings of the same subject in the Neapolitan area.

At San Giovanni Battista lying was devoted to the recent exhibition at the Museum Het Rembranthuis of Amsterdam between 2010 and 2011: to report in this regard, the publication on exposure, interventions Strinati (2010-2011), Treffers (2010–2011), Pacelli (2010-2011), which traces back the historical and critical of the painting on the basis of the findings in 1994 (pp.