Jorge Juan y Santacilia

Jorge Gaspar Juan y Santacilia (Novelda, Alicante, 5 January 1713 – Madrid, 21 June 1773) was a Spanish mariner, mathematician, natural scientist, astronomer, engineer, and educator.

As a young naval lieutenant, Juan participated in the French Geodesic Mission to the Equator of 1735–1744, which established definitively that the shape of the Earth is an oblate spheroid, flattened at the poles, as predicted in Isaac Newton's Principia.

With his fellow lieutenant Antonio de Ulloa, Juan travelled widely in the territories of the Viceroyalty of Peru and made detailed scientific, military, and political observations of the region.

Under Ensenada's orders, Juan undertook an eighteen-month mission of industrial espionage in London, after which he worked tirelessly to modernize and professionalize naval architecture and other operations in Spain.

In 1760 Juan was appointed as Squadron Commander, the most senior officer in the Spanish Navy, but ill health soon forced him to give up that role and instead take up diplomatic and educational missions.

In fact, Jorge had been baptized in the parish of Monforte, rather than that of Novelda (his actual place of birth) in order to render him eligible for a benefice attached to the Collegiate Church of Saint Nicholas, in Alicante, should he eventually pursue an ecclesiastical career.

[4] Juan then returned to Spain and applied for admission to the Royal Company of Marine Guards, the Spanish naval academy, located in the port city of Cádiz.

Upon the recommendation of his First Secretary of State José Patiño, Philip appointed to that role Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, who were then 21 and 18 years old, respectively.

[5] The equatorial expedition was led by three members of the French Academy of Sciences: the astronomer Louis Godin, and geographers Charles Marie de La Condamine and Pierre Bouguer.

The geodesic work around the equator finally began in September 1736 with the measurement of the distance between two base points chosen to lie on the plain of Yaruquí, outside the city of Quito.

Those points then served as baseline for the triangulation with which the members of the mission measured an arc of about three degrees of latitude that extended to the south, past Riobamba and up to an endpoint near the city of Cuenca.

[5] After the War of Jenkins' Ear broke out between Spain and Great Britain in 1739, Juan and Ulloa were called upon to help organize the defense of the Peruvian coast.

[7] Commodore Anson had set out in from England in September of 1740 with orders to sail around Cape Horn and then attack Spanish ships and settlements along the Pacific coast.

Their military responsibilities due to the war with Britain kept Juan and Ulloa from scientific work for long periods and further delayed the completion of the geodesic measurements.

Juan and Ulloa also objected to the proposed inscription, which named only the three scientists who were members of the French Academy of Sciences: Godin, Bouger, and La Condamine.

All of the topographical and astronomical measurements were concluded towards the end of 1742, and by March 1743 the members of the mission agreed on the result that they had been seeking: one degree of latitude around the equator corresponded to an arc length of 56,753 toises.

[5] Together with the work of the Arctic expedition led by Maupertuis and with geodesic measurements carried out in France, this established unequivocally that the Earth is an oblate spheroid, i.e. flattened at the poles, as Newton had predicted.

During the mission, Juan also successfully used a barometer to measure the heights of several of the peaks of the Andes, based on the formulas developed for that purpose by Edme Mariotte and Edmond Halley.

[3] At the end of 1744, Juan and Ulloa embarked for Europe on two different French ships, each carrying their own copies of their scientific and other papers, in order to minimize the risk that their work would be lost in the homeward journey.

Juan, who was the more mathematically inclined of the two, was largely responsible for writing the Astronomical and Physical Observations Made by Order of His Majesty in the Kingdoms of Peru, which contained his calculations of the figure of the Earth.

The publication of the book was held up by the Spanish Inquisition because Juan worked within the framework of the heliocentric cosmology, which the Catholic church still officially regarded as heretical after the condemnation of Galileo more than a century earlier.

[3] The Inquisition allowed the publication of the book to proceed in 1748, after Juan modified the text to present heliocentrism as a hypothesis adopted for purposes of calculation.

[3] The purpose of that work was to determine precisely the line of demarcation as defined by the terms of the Treaty of Tordesillas between Spain and Portugal, signed in 1494 under the sponsorship of Pope Alexander VI.

[9] That report paints a dire picture of the social and political situation of the Viceroyalty of Peru in 1730s and 1740s, alleging many grave instances of lawlessness and mismanagement by the civil and church authorities in the region.

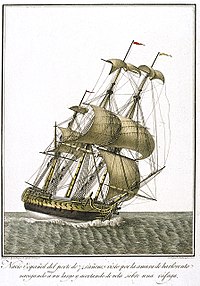

Juan's principal task was to learn about the design of the latest British warships and to recruit some of the constructors in order to help the Spanish Navy to improve its outdated fleet.

He was also tasked with collecting information about the English manufacture of fine cloth, sealing wax, printing plates, dredges, and armaments, to purchase surgical instruments for the Royal College of Naval Surgeons, in Cádiz, and to procure steam engines to pump water out of mines.

He implemented a modern industrial system of division of labor among the different disciplines involved in the construction of warships, such as dry-docks, shipyards, furnaces, rigging, and canvas making.

Juan promoted the teaching of differential and integral calculus in the Spanish military academies and helped to supply those institutions with modern scientific equipment.

That institution had been created in 1725 by Philip V to train the children of Spain's aristocracy in military and civil administration, but it had declined after the expulsion of the Jesuits (who had been in charge of the Seminary) in 1767.