José María Valiente Soriano

[19] In 1933[20] Valiente married a girl from Santander, Consuelo Setién Rodríguez (died 1986);[21] she was descendant to a family of noble Cantabrian landowners[22] and would later claim the title of Marqués de Pelayo.

Among other relatives the best known is his nephew[28] Alfredo Prieto Valiente, who was an important Asturian politician and in the years of 1977-1979 served as the Unión de Centro Democrático deputy to the Constituent Cortes.

[46] It is not exactly clear to what extent this mission was agreed with the party leader José Gil-Robles, since the two gave conflicting accounts of the incident, but it is usually accepted that the latter was at least approvingly aware.

[47] When the news of the Fontainebleau talks leaked to the press CEDA, the party which despite repeated declarations of loyalty towards the Republic was customarily accused of anti-Republican designs by the Left, found itself cornered and embarrassed.

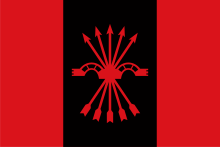

The JAP militancy and the monarchist episode, embarrassing to the loyalist CEDA, were welcome credentials for the Traditionalists, who made little secret of their intention to do away with the godless regime as soon as possible.

[61] Initially he seemed to have been among hardline falcondistas, but later tended to cautious endorsement of compliance[62] and engaged in talks on details of the merger, apparently in hope that some genuine understanding might be achieved.

[63] When Unification Decree was made public Valiente resigned his post as secretary of the Junta; he admitted that the merger conflicted with his feelings and that "there is no moral unity" between the merged parties,[64] but argued that given the circumstances, it had to be accepted.

[71] As member of Consejo Valiente was bombarded with letters of protest and requests for assistance on part of the Carlists who complained about Falangist domination, marginalisation of Traditionalism and personal persecutions; however, there was almost nothing he could have done about it.

[81] In 1945 he attended a grand Carlist anti-Francoist demonstration in Pamplona and delivered an address from the balcony;[82] afterwards he was detained by security and expected facing the firing squad;[83] eventually the sanctions adopted were relatively mild, especially compared to the terror employed against the Left.

The latter invited him to join the juanistas, the group notionally loyal to the regency, but pressing the candidacy of Don Juan, the Alfonsist claimant, as the prospective Carlist king.

Since the early 1950s at meetings of the Carlist command layer Valiente started to make references about "new political situation", thought to be hints about the need to seek rapprochement with the regime.

[92] Consistently opposing the plans of monarchical union, pursued by José María Arauz de Robles, Valiente engineered a more collaborative approach towards Francoism.

[93] The time seemed particularly opportune in 1957, when totalitarian plans of the Falangist leader José Arrese were rejected by Franco; the dictator started to make references to Traditionalism and to movimiento-comunión.

[94] The new strategy of posibilismo was welcomed with mixed feelings among the Carlists; older regional junteros grumbled and a young Navarrese, disguised as a priest, assaulted Valiente in a Pamplona street.

[95] His key ally against the internal opposition turned out to be the son of Don Javier, Carlos Hugo, who made a fulminant Príncipe de Asturias entry at the 1957 annual Carlist Montejurra amassment.

The prince, greeted with exploding enthusiasm of the youth, delivered his La Proclama de Montejurra which, apart from social novelties, presaged modernization of the party and a more activist policy; it might have been interpreted as an offer to Franco.

[96] However, this in turn triggered two secessions, which Valiente was not able to prevent; in 1957 so-called Estorilos declared Don Juan the legitimate Carlist heir,[97] and in 1958 the anti-Francoist intransigents created a splinter faction named RENACE.

In early 1962 Carlos Hugo moved permanently from France to Madrid[100] and set up Secretaría Política, a team of his young collaborators, led by Ramón Massó.

[110] Following setup of Secretaría Política in 1962, other new bodies mushroomed and diluted the powers of jefe delegado, with Masso and José Maria Zavala emerging as dynamic new leaders.

What started to amount to an open friction was not merely a personalist squabble; Zamanillo and Traditionalist theorists like Francisco Elias de Tejada were alarmed by ambiguous, socially-driven rhetoric of the carlohuguistas.

[111] The conflict climaxed in 1963, when Zamanillo was expulsed,[112] Sáenz-Díez was demoted from treasury, while intellectuals related to the Siempre magazine, like Elias de Tejada and Rafael Gambra, distanced themselves from the organization.

[117] In 1965 Valiente was again admitted by Franco; during the conversation he realized that collaboration has reached its limits, that no more concessions could be expected and that the crowning of Don Carlos Hugo was not even a distant perspective.

[124] Valiente was bombarded with alarm messages which denounced subversive revolutionary infiltration of Carlism; however, guided by loyalty to the king, which seemed to have endorsed the course advanced by his son, and judging the charges as exaggerated, he did not mount firm opposition.

[125] Increasingly bewildered, isolated, in disagreement with the course promoted by the prince and consumed by tension, he tried to hand his resignation as jefe delegado; it was eventually accepted by Don Javier in late 1967[126] and made public in early 1968.

[142] Following relaxation of the law on political organizations, para-political groupings were no longer needed; Valiente started working around a new broadly based monarchist party, possibly with titular presidency of Juan Carlos.

[143] The organization eventually materialized in 1975 as Unión Nacional Española, but following internal disagreements Valiente left it already in early 1976;[144] some doubted his credibility quoting the secret 1934 talks with Alfonso XIII.

[146] He voted in favor of Ley para la Reforma Política, dubbed "suicide of the Francoist Cortes";[147] as the chamber was dissolved Valiente lost his mandate in 1977.