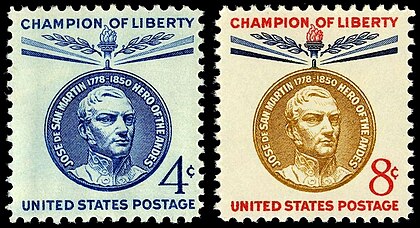

José de San Martín

Born in Yapeyú, Corrientes, in modern-day Argentina, he left the Viceroyalty of the Río de la Plata at the early age of seven to study in Málaga, Spain.

In 1812, he set sail for Buenos Aires and offered his services to the United Provinces of the Río de la Plata, present-day Argentina and other countries.

San Martín is regarded as a national hero of Argentina, Chile, and Peru, a great military commander, and one of the Liberators of Spanish South America.

They met at the house of Carlos María de Alvear, other members were José Miguel Carrera, Aldao, Blanco Encalada and other criollos, American-born Spaniards.

[16] San Martín, Alvear and Zapiola established a local branch of the Lodge of Rational Knights, along with morenists, the former supporters of the late Mariano Moreno.

Juan Martín de Pueyrredón promoted antimorenist new members, Manuel Obligado and Pedro Medrano, by preventing the vote of three deputies and thus achieving a majority.

A royalist, probably Zabala himself,[23][24] attempted to kill San Martín while he was trapped under his dead horse where he suffered a saber injury to his face, and a bullet wound to his arm.

Oral tradition has it that the premiere took place on 14 May 1813 at the home of aristocrat Mariquita Sánchez de Thompson, with San Martín also attending, but there is no documentary evidence of that.

Alvear opposed the merchants and the Uruguayan caudillo José Gervasio Artigas, San Martín thought that it was risky to open such conflicts when the royalists were still a threat.

The Army of the North, which was operating at the Upper Peru, was defeated at the battles of Vilcapugio and Ayohuma, so the triumvirate appointed San Martín to head it, replacing Manuel Belgrano.

After an interview with Tomás Guido, San Martín came up with a plan: organize an army in Mendoza, cross the Andes to Chile, and move to Peru by sea; all while Güemes defended the north frontier.

San Martín's plan was complicated as well by the Disaster of Rancagua, a royalist victory that restored absolutism in Chile, ending the Patria Vieja period.

A combination of incentives, confiscations and planned economy allowed the country to provision the army: gunpowder, pieces of artillery, mules and horses, food, military clothing, etc.

San Martín and Guido wrote a report in the autumn of 1816, detailing to the Supreme Director Antonio González de Balcarce the full military plan of operations.

General Manuel Belgrano, who had made a diplomatic mission to Europe, informed them that independence would be more easily acknowledged by the European powers if the country established a monarchy.

Incapable of financial support, Buenos Aires sent lawyer Manuel Aguirre to the United States, to request aid and acknowledge the declaration of independence.

The Chilean José Miguel Carrera had obtained his own ships after the disaster of Rancagua which he intended to use to liberate Chile, however, as this had already been achieved by San Martín, he subsequently refused to place his fleet under the Army of the Andes.

[78] The army was reorganized again, but the deaths, injuries and desertions caused by the defeat at Cancha Rayada reduced its size to 5,000 soldiers, which was closer to the royalist forces.

At the end of the battle, the royalists had been trapped among the units of Las Heras in the west, Alvarado in the middle, Quintana in the east and the cavalries of Zapiola and Freire.

Pueyrredón initially declined to give further help, citing the conflicts with the federal caudillos and the organization of a huge royalist army in Cádiz that would try to reconquer the La Plata basin.

He calculated that Artigas might condition the peace on a joint declaration of war to colonial Brazil; so San Martín proposed to defeat the royalists first and then demand the return of the Eastern Bank to the United Provinces.

[90] Although Artigas was defeated by the Luso-Brazilian armies, his allies Estanislao López and Francisco Ramírez continued hostilities against Buenos Aires for its inactivity against the invasion.

[95] The rebellion of Spanish general Rafael del Riego and an outbreak of yellow fever in the punitive expedition organized in Cádiz ended the royalist threat to Buenos Aires.

He also tried to promote rebellions and insurrection within the royalist ranks, and promised the emancipation of any slaves that deserted their Peruvian masters and join the army of San Martín.

The viceroy's deputies proposed to adopt the liberal Spanish constitution if San Martín left the country, but the patriots requested instead that Spain grant the independence of Peru.

[107][108] As hostilities renewed, San Martín organized several guerrilla groups in the countryside, and laid siege to Lima, but did not force his entry, as he did not want to appear as a conqueror to the local population.

With this approval, the authority in Lima, the support of the northern provinces and the port of El Callao under siege, San Martín declared the independence of Peru on 28 July 1821.

[128] By this time the federal Juan Manuel de Rosas had begun to pacify the civil war started by Lavalle and earned San Martín's admiration.

[citation needed] Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic has an avenue named Jose de San Martin in his honor that connects the colonial zone to the west of the city.

[citation needed] The statue was erected through purely private initiative, with the support of national government of Argentina, the municipal council of Buenos Aires and a public funding campaign.