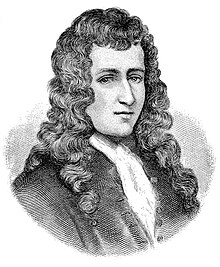

Antoine Lefèbvre de La Barre

After handing Cayenne over to his brother, he served briefly as lieutenant-general of the French West Indies colonies, then for many years was a naval captain.

He spent much of his energy in trading ventures, using his position as governor to attack his great rival René-Robert Cavelier de La Salle.

He began a war with the Iroquois, the main power in the region, and led a poorly equipped expedition against them that ran into difficulty.

He was forced to agree to a disadvantageous peace treaty that was condemned by France's Indian allies, the colonists and the French court.

[1][2] Their children included Robert (born c. 1647), François Antoine, Seigneur de La Barre (1650–1727), Marguerite (1651–1725) and Jeanne Françoise (1654–1735).

The French would let the Dutch military march out, drums beating, and would give them and all other inhabitants transport with their goods and slaves to their destination island or country, providing food and drink on the voyage.

[5] He obtained the appointment of his younger brother Cyprien Lefebvre de Lézy as governor of Cayenne from the West Indies Company.

The intendant at Rochefort, Charles Colbert du Terron [fr]), told the minister that La Barre was a poor choice as leader of this expedition since he had no stomach for war.

[6] On 7 October 1666 La Barre presented himself to the council on Martinique and registered his commission, dated 26 February 1666, to command the vessels and maritime forces of the islands.

[16] Soon after he called an assembly of the senior officers and leading inhabitants of the island to hear their complaints concerning commerce and to respond on behalf of the company.

[1] A letter patent from the king date 1 February 1667 confirmed La Barre as lieutenant-general of the French armies, islands and mainland of America.

La Barre learned that the garrison of the English Governor Roger Osborne included many Irish Catholics of dubious loyalty, and decided to land a few days later.

La Barre proposed joint action against the English, which became more urgent when word arrived that Saint Christopher Island was being blockaded by Berry.

He was accompanied by his wife Marie, his daughter Anne-Marie, his son-in-law Rémy Guillouet d'Orvilliers, captain of the guards, and the intendant Jacques de Meulles.

[6] La Barre was personally instructed by Louis XIV that he must focus on restoring order and good government and must do everything to avoid internal disputes between the colonists, which had done great damage under Frontenac.

[28] La Barre wrote letters to the king and the Navy minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert de Seignelay in which he said that unlike his predecessors he did not intend to engage in trade for his personal benefit.

[29] On 10 October 1682 La Barre met with the military and religious leaders of New France to discuss the general situations and the threat from the Iroquois confederation, particularly the Tsonnontouans (Senecas) .

[31] He reported that they demanded that René-Robert de La Salle be forced to leave Fort Saint-Louis, a post on the Illinois River.

[1] Francis Parkman (1823–1893) wrote in The Discovery of the Great West (1874), La Barre showed a weakness and an avarice for which his advanced age may have been in some measure answerable.

[28] In 1682 La Barre founded the Compagnie du Nord trading company to compete with the Hudson Bay traders.

[1] La Barre gave Daniel Greysolon, Sieur du Lhut a 3-year commission early in 1683 to take an expedition of 15 canoes to the western Great Lakes and the upper Mississippi.

[32] De Meulles charged in a report of 10 October 1684 that La Barre had merchandise for his personal trading ventures carried by military supply convoys.

La Barre tried unsuccessfully to get Thomas Dongan, 2nd Earl of Limerick, governor of New York, to stop supporting the Iroquois and selling them goods at lower prices than the French.

The Intendant de Meulles accused La Barre in his letters to Seignelay of selling large numbers of licenses to fur traders and of trading with the English and the Dutch.

The Jesuits, who had much experience in dealing with the Indians, advised La Barre to avoid provoking the Iroquois, while the leading men of Quebec wanted to delay war until there was no longer any chance of a negotiated peace, and until fresh troops had arrived from France.

[35] Despite this advice, La Barre launched a war on the Iroquois in the summer of 1684, apparently in order to force them to trade with the French rather than the English.

On 30 July 1684 the king wrote to La Barre agreeing with the decision, which had been presented as a response to the attack on Fort Saint-Louis.

[1] La Barre left Montreal on 30 July 1684 with 700 militiamen, 400 Indian allies and 150 regular troops, and travelled to Fort Frontenac.

[37] The Onondaga leader Garangula said, "Hear, Yonnondio, take care for the future, that so great a number of soldiers as appear here do not choke the Tree of Peace planted in so small a fort.

On 10 March 1685 Louis XIV wrote a letter to Muelles that said La Barre was to be recalled after the shameful peace he had just concluded, replaced by the Marquis de Denonville.