Joseph Demarco

More so since the then Grand Master of the Knights Hospitallers, António Manoel de Vilhena, had given free entry to the harbours to all nations.

Fortunate enough to be born within a well-off family, Demarco was given a good education (including a solid knowledge of Latin), probably at the Collegium Melitense of the Jesuits in Valletta, Malta.

Already as a young boy, his medical intellectual curiosity drew him to speculate about the effect of atmospheric conditions on the human body, as his writing from 1733 (De Aere),[4] at only fifteen years of age, attests.

Of course, he was also very much interested in understanding physical illnesses, as his writing from 1741 (De Tumoribus Humoralibus),[5] on swellings caused by liquid retention, shows.

This is also attested by a document written by Demarco, Physiologie Cursus: Anatomico – meccanico – experimentalis (A Course in Physiology: Anatomical – mechanical – experimental; 1765) which originates from De Sauvages’ course on the subject.

[13] In all probability, it was this dexterity and expertise which convinced his lecturers to trust him, from amongst his peers, with a course on physics (as his Traité de Physique attests).

It was entitled Dissertatio Physiologica de Respiratione, ejusque Uso Primario (Physiological Aspects of Respiration and its Primary Significance).

On the contrary, he was a close collaborator and a personal friend of the Grand Master of the Knights Hospitallers, Manuel Pinto da Fonseca, who immediately, on Demarco's return to Malta, chose him as Principle Medical Officer for the Maltese Islands.

All of his speculative reflections, including his philosophical ones, squarely rest on the authority of concrete experience and on pure sense data.

Though highly proficient from a professional point of view, Demarco was consistently appealed by the theoretical foundations of the medical art and by the intellectual and academic relationships which particular illnesses suggested.

While in Tripoli he continued to indulge his scientific and philosophical curiosity by making copiousness notes about the quality of the soil, the atmosphere, and also about local customs.

The Order of Knights Hospitallers which he loved was fatally in trouble, not only because of the revolution in France, but also for its internal bankruptcy, corruption, and loose morals.

Though some interest in the man's activities and intellectual endeavours had always been kept alive amongst academics, little serious effort had ever been made to bring his scientific and philosophical accomplishments fully out in the open.

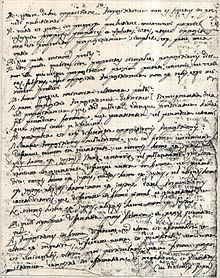

All manuscripts are written in Demarco's typical minuscule, crammed and barely legible handwriting, which of course makes reading, transliteration, translation and study immensely difficult.

Though the outlines of some of his work are generally identified and acknowledged, the greater number of his compositions remain unfamiliar and shrouded in obscurity.