Josephinism

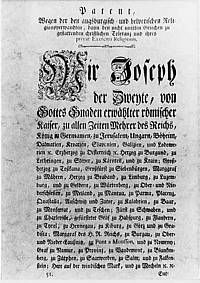

During the ten years in which Joseph was the sole ruler of the Habsburg monarchy (1780–1790), he attempted to legislate a series of drastic reforms to remodel Austria in the form of what liberals saw as an ideal Enlightened state.

He inherited the crown of the Holy Roman Empire in 1765, on the death of his father, but ruled the Habsburg lands only as the junior co-regent to his mother, the matriarch Maria Theresa, until 1780.

These included the suppression of 71 of the 467 monasteries in Lombardy, then an Austrian possession, an increase of the minimum age for monks to 24,[2] a prohibition of further gifts of land to the Church unless permitted by the government, the effective dissolution of the Jesuit order by seizing their properties and removing their long held dominance in education, and an Urbarium law limiting some of the feudal obligations of peasants to their lords in Bohemia.

[3] These measures, although influenced by Joseph, were largely directed by Maria Theresa and Kaunitz, demonstrating that Josephinism as a political force predated its eponymous creator, albeit in a less radical form.

At the heart of this "Josephinism" lay the idea of the unitary state, with a centralized, efficient government, rational and mostly secular society, with greater degrees of equality and freedom, and fewer arbitrary feudal institutions.

Robin Okey, in The Habsburg Monarchy, describes it as the replacement of the forced serf labor system by the division of landed estates (including the demesne) among rent-paying tenants".

[5] In 1783, Joseph's advisor Franz Anton von Raab was instructed to extend this system to all lands owned directly by the Habsburg crown in Bohemia and Moravia.

In communities with large Protestant or Orthodox minorities, churches were allowed to be built, and social restrictions on vocations, economic activity, and education were removed.

Assistance offered by Prussia was refused by Cardinal Firmian's successor, Bishop Joseph Franz Auersperg, an adherent of Josephinism.

In return Passau gave up its diocesan rights and authority in Austria, including the provostship of Ardagger, and bound itself to pay 400,000 florins ($900,000), afterwards reduced by the emperor to one-half toward the equipment of the new diocese.

As early as 1785 the Viennese ecclesiastical order of services was made obligatory, "in accordance with which all musical litanies, novenas, octaves, the ancient touching devotions, also processions, vespers, and similar ceremonies, were done away with."

Nevertheless there could be no durable peace with the bureaucratic civil authorities, and Bishop Ernest Johann Nepomuk von Herberstein was repeatedly obliged to complain to the emperor of the tutelage in which the Church was kept, but the complaints bore little fruit.

Popular revolts and protests—led by nobles, seminary students, writers, and agents of Prussian King Frederick William—stirred throughout the Empire, prompting Joseph to tighten censorship of the press.