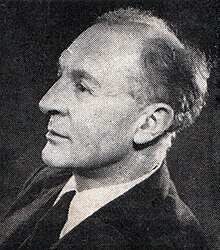

Joyce Cary

Arthur Joyce Lunel Cary was born in 1888 in his grandparents' home, which was above the Belfast Bank on Shipquay Street in Derry in Ulster, the Northern province in Ireland.

However, the family had largely lost its Inishowen property on the western shores of Lough Foyle after the passage of the Irish Land Act in 1882.

Although Cary remembered his West Ulster childhood with affection and wrote about it with great feeling, he was based in England for the rest of his life.

The feeling of displacement and the idea that life's tranquillity may be disturbed at any moment marked Cary and informs much of his writing.

[5] Seeking adventure, in 1912 Cary left for the Kingdom of Montenegro and served as a Red Cross orderly during the Balkan Wars.

Returning to Britain the next year, Cary sought a post with an Irish agricultural cooperative scheme, but the project fell through.

Dissatisfied and believing that he lacked the education that would provide him with a good position in the United Kingdom, Cary joined the Nigerian political service.

The short story "Umaru" (1921) describes an incident from this period in which a British officer recognises the common humanity that connects him with his African sergeant.

[citation needed] By 1920, Cary was concentrating his energies on providing clean water and roads to connect remote villages with the larger world.

Cary had thought this impossible for financial reasons, but in 1920, he obtained a literary agent and some of the stories he had written while in Africa were sold to The Saturday Evening Post, an American magazine, and published under the name Thomas Joyce.

[7][8] Cary worked hard on developing as a writer, but his brief economic success soon ended as the Post decided that his stories had become too "literary".

But Charley Is My Darling (1940), about displaced young people at the start of World War II, found a wider readership, and the memoir A House of Children (1941) won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for best novel.

He began preparing a series of prefatory notes for the re-publication of all his works in a standard edition published by Michael Joseph.

He visited the United States, collaborated on a stage adaptation of Mister Johnson, and was offered an appointment as a CBE, which he refused.

[14] As his physical powers failed, Cary had to have a pen tied to his hand and his arm supported by a rope to write.