Telecine

The kinescope was used to record the image from a television display to film, synchronized to the TV scan rate.

[3] Non-live programming could also be filmed using the kinescope, edited mechanically as normal, and then played back for TV.

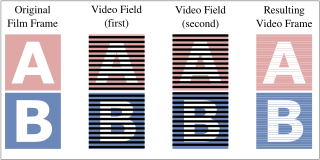

A more advanced technique is to use 2:3 pulldown, discussed below, which turns every second frame of the film into three fields of video, which results in a slightly smoother display.

The most complex part of telecine is the synchronization of the mechanical film motion and the electronic video signal.

In countries that use the PAL or SECAM video standards, film destined for television is photographed at 25 frames per second.

In the United States and other countries where television uses the 59.94 Hz vertical scanning frequency, video is broadcast at ≈29.97 frame/s.

In fact, the 3-2 notation is misleading because according to SMPTE standards for every four-frame film sequence the first frame is scanned twice, not three times.

This method was born out of a frustration with the faster, higher-pitched soundtracks that traditionally accompanied films transferred for PAL and SECAM audiences.

This brings the refresh rate from 25 frames/s to exactly 60,000/1001, or ≈59.94, fields per second, with no change whatsoever in speed, duration, or audio pitch.

PAL material in which 2:3 (Euro) pulldown has been applied suffers from a similar lack of smoothness, though this effect is not usually called telecine judder.

It is also possible, but more difficult, to perform reverse telecine without prior knowledge of where each field of video lies in the 2:3 pulldown pattern.

Edits performed on film material after it undergoes 2:3 pulldown, e.g. in NTSC format, can introduce jumps in the pattern if care is not taken to preserve the original frame sequence.

Most reverse telecine algorithms attempt to follow the 2:3 pattern using image analysis techniques, e.g. by searching for repeated fields.

In the United Kingdom, Rank Precision Industries was experimenting with the flying-spot scanner (FSS), which inverted the cathode-ray tube (CRT) concept of scanning using a television screen.

In 1950 the first Rank flying spot monochrome telecine was installed at the BBC's Lime Grove Studios.

[12] The CRT in the FSS emits a pixel-sized electron beam which excites phosphors coating the envelope, causing them to glow in red, green, and blue.

The Mark series was then replaced by the Ursa (1989), the first in their line of telecines capable of producing digital data in 4:2:2 color space.

[13] The Robert Bosch GmbH, Fernseh division[a] introduced the world's first charge-coupled device (CCD) telecine (1979), the FDL 60.

In 2000 Philips introduced the Shadow Telecine (STE), a low-cost version of the Spirit with no Kodak parts.

The Spirit DataCine, Cintel's C-Reality and ITK's Millennium opened the door to the technology of digital intermediates, wherein telecine tools were not just used for video outputs, but could now be used for high-resolution data that would later be recorded back out to film.

[15] The Scanity uses time delay integration (TDI) sensor technology for extremely fast and sensitive film scans.

An array of high-power multiple red, green and blue LEDs is pulsed just as the film frame is positioned in front of the optical lens.

[16] Cameras that record 25 frames/s (PAL) or 29.97 frames/s (NTSC) do not need to employ 2:3 pulldown, because every progressive frame occupies exactly two video fields.

In NTSC countries, most digital broadcasts of 24 frame/s progressive material, both standard and high definition, continue to use interlaced formats with 2:3 pulldown, even though ATSC allows native 24 and 23.976 frame/s progressive formats which offer the greatest image quality and coding efficiency, and are widely used in motion picture and high definition video production.

For example, a 1080p 120 Hz set which accepts a 1080p24 input can achieve 5:5 pulldown by simply repeating each frame five times and thus not exhibit picture artifacts associated with telecine judder.

Numerous techniques have been tried to minimize gate weave, using both improvements in mechanical film handling and electronic post-processing.

In the hard-telecined case, video is stored on the DVD at the playback framerate (29.97 frame/s for NTSC, 25 frame/s for PAL), using the telecined frames as shown above.

In the soft-telecined case, the material is stored on the DVD at the film rate (24 or 23.976 frames/s) in the original progressive format, with special flags inserted into the MPEG-2 video stream that instruct the DVD player to repeat certain fields so as to accomplish the required pulldown during playback.

[18] Progressive scan DVD players additionally offer output at 480p by using these flags to duplicate frames rather than fields, or if the TV supports it, to play the disc back at the native 24p rate.

In the case of PAL DVDs using 2:2 pulldown, the difference between soft and hard telecine vanishes, and the two may be regarded as equal.