Judicial Procedures Reform Bill of 1937

Roosevelt sought to reverse this by changing the makeup of the court through the appointment of new additional justices who he hoped would rule that his legislative initiatives did not exceed the constitutional authority of the government.

Members of both parties viewed the legislation as an attempt to stack the court, and many Democrats, including Vice President John Nance Garner, opposed it.

[7][8] He asked, "Can it be said that full justice is achieved when a court is forced by the sheer necessity of its business to decline, without even an explanation, to hear 87% of the cases presented by private litigants?"

[9] Three weeks after the radio address, the Supreme Court published an opinion upholding a Washington state minimum wage law in West Coast Hotel Co. v.

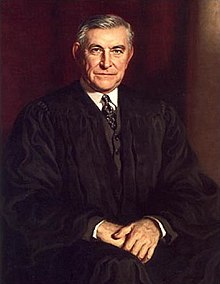

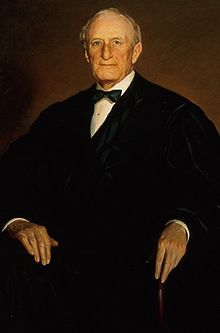

[10] The 5–4 ruling was the result of the apparently sudden jurisprudential shift by Associate Justice Owen Roberts, who joined with the wing of the bench supportive to the New Deal legislation.

This reversal came to be known as "the switch in time that saved nine"; however, recent legal-historical scholarship has called that narrative into question[11] as Roberts' decision and vote in the Parrish case predated both the public announcement and introduction of the 1937 bill.

Other reasons for its failure included members of Roosevelt's own Democratic Party believing the bill to be unconstitutional, with the Judiciary Committee ultimately releasing a scathing report calling it "a needless, futile and utterly dangerous abandonment of constitutional principle ... without precedent or justification".

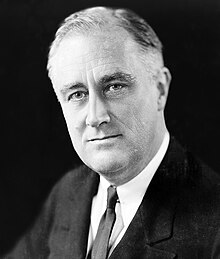

[17] Following the Wall Street Crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression, Franklin Roosevelt won the 1932 presidential election on a promise to give America a "New Deal" to promote national economic recovery.

Shortly after Roosevelt's inauguration, Congress passed the Economy Act, a provision of which cut many government salaries, including the pensions of retired Supreme Court justices.

As Interior Secretary Harold Ickes complained, Attorney General Homer Cummings had "simply loaded it [the Justice Department] with political appointees" at a time when it would be responsible for litigating the flood of cases arising from New Deal legal challenges.

[23] Compounding matters, Roosevelt's congenial Solicitor General, James Crawford Biggs (a patronage appointment chosen by Cummings), proved to be an ineffective advocate for the legislative initiatives of the New Deal.

[21] This disarray at the Justice Department meant that the government's lawyers often failed to foster viable test cases and arguments for their defense, subsequently handicapping them before the courts.

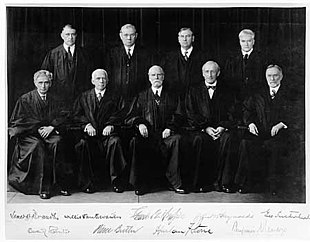

While it is true that many rulings of the 1930s Supreme Court were deeply divided, with four justices on each side and Justice Roberts as the typical swing vote, the ideological divide this represented was linked to a larger debate in U.S. jurisprudence regarding the role of the judiciary, the meaning of the Constitution, and the respective rights and prerogatives of the different branches of government in shaping the judicial outlook of the Court.

As William Leuchtenburg has observed: Some scholars disapprove of the terms "conservative" and "liberal", or "right, center, and left", when applied to judges because it may suggest that they are no different from legislators; but the private correspondence of members of the Court makes clear that they thought of themselves as ideological warriors.

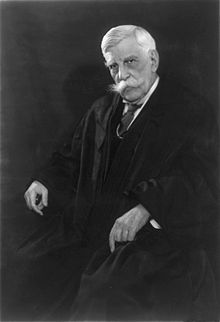

One of the most famous proponents of this concept, known as the Living Constitution, was U.S. Supreme Court justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., who said in Missouri v. Holland the "case before us must be considered in the light of our whole experience and not merely in that of what was said a hundred years ago".

This approach favored sorting laws into categories that demanded deference towards other branches of government in the economic sphere, but aggressively heightened judicial scrutiny with respect to fundamental civil and political liberties.

With the Judiciary Bill, Roosevelt sought to accelerate this judicial evolution by diminishing the dominance of an older generation of judges who remained attached to an earlier mode of American jurisprudence.

Blaisdell concerned the temporary suspension of creditor's remedies by Minnesota in order to combat mortgage foreclosures, finding that temporal relief did not, in fact, impair the obligation of a contract.

With several cases laying forth the criteria necessary to respect the due process and property rights of individuals, and statements of what constituted an appropriate delegation of legislative powers to the President, Congress quickly revised the Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA).

[44] However, an autumn 1935 Gallup Poll had returned a majority disapproval of attempts to limit the Supreme Court's power to declare acts unconstitutional.

[55][56] Roosevelt and Cummings authored accompanying messages to send to Congress along with the proposed legislation, hoping to couch the debate in terms of the need for judicial efficiency and relieving the backlogged workload of elderly judges.

The administration wanted to introduce the bill early enough in the Congressional session to make sure it passed before the summer recess, and, if successful, to leave time for nominations to any newly created bench seats.

[64] Roosevelt's own Vice President John Nance Garner expressed disapproval of the bill holding his nose and giving thumbs down from the rear of the Senate chamber.

Two other founders, Amos Pinchot, a prominent lawyer from New York, and Edward Rumely, a political activist, had both been Roosevelt supporters who had soured on the President's agenda.

Among the original members of the committee were James Truslow Adams, Charles Coburn, John Haynes Holmes, Dorothy Thompson, Samuel S. McClure, Mary Dimmick Harrison, and Frank A. Vanderlip.

Attorney General Cummings' testimony was grounded on four basic complaints: Administration advisor Robert H. Jackson testified next, attacking the Supreme Court's alleged misuse of judicial review and the ideological perspective of the majority.

[79] On March 29, 1937, the court handed down three decisions upholding New Deal legislation, two of them unanimous: West Coast Hotel Co. v. Parrish,[10] Wright v. Vinton Branch,[80] and Virginia Railway v.

[92] On June 14, the committee issued a scathing report that called FDR's plan "a needless, futile and utterly dangerous abandonment of constitutional principle ... without precedent or justification".

[103] This new law required that: A political fight which began as a conflict between the President and the Supreme Court turned into a battle between Roosevelt and the recalcitrant members of his own party in the Congress.

As Michael Parrish writes, "the protracted legislative battle over the Court-packing bill blunted the momentum for additional reforms, divided the New Deal coalition, squandered the political advantage Roosevelt had gained in the 1936 elections, and gave fresh ammunition to those who accused him of dictatorship, tyranny, and fascism.