Julia Stephen

Through another maternal aunt, she became a frequent visitor at Little Holland House, then home to an important literary and artistic circle, and came to the attention of a number of Pre-Raphaelite painters who portrayed her in their work.

Devastated, she turned to nursing, philanthropy and agnosticism, and found herself attracted to the writing and life of Leslie Stephen, with whom she shared a friend in Anny Thackeray, his sister-in-law.

[5][6] While Dr Jackson came from humble origins, but had a successful career that brought him into circles of influence, the Pattles moved naturally in the upper echelons of Anglo-Bengali society.

[5][6] Maria Pattle was the fifth of seven sisters famed for their beauty, verve and eccentricity, and who inherited some Bengali blood through their maternal grandmother, Thérèse Josephe Blin de Grincourt.

[18] Sarah Monckton Pattle (1816-1887), had married Henry Thoby Prinsep (1793–1878), an administrator with the East India Company, and their home at Little Holland House was an important intellectual centre and influence on Julia, that she would later describe to her children as "bohemian".

There one might find Disraeli, Carlyle, Tennyson and Rossetti taking tea and playing croquet, while the painter George Frederic Watts (1817–1904) lived and worked there, as did for a while Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898).

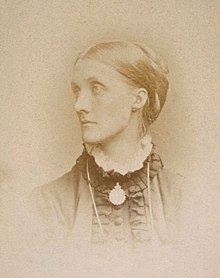

[32] At 5 feet 6 inches (1.68 metres) she was tall for a Victorian woman and had large, practical hands, deriding "the lovely filbert nails which are the pride of many",[f] shunning vanity, fashion and affectation.

[34] On 1 February 1867, at the age of 21, Julia became engaged to Herbert Duckworth, a member of the Somerset landed gentry,[g][36][37] a graduate of Cambridge University and Lincoln's Inn (1858),[38] and now a barrister and they were married on 4 May at Frant.

[42] Leslie Stephen felt "a touch of pain" later, in writing about the purity of their love, commenting on her letters to Herbert, he stated that she "made a complete surrender of herself in the fullest sense: she would have no reserves from her lover, and confesses her entire devotion to him".

[49] Leslie Stephen observed that "a cloud rested even upon her maternal affections ...it seemed to me at the time that she had accepted sorrow as her lifelong partner",[50] and that "she was like a person reviving from drowning" and sometimes felt as if "she must let herself sink".

[61] Leslie Stephen, a former Cambridge Don and man of letters, "knew everyone" in the literary and artistic scene, and came from a respectable upper-middle-class family of lawyers, country gentlemen and clergy.

[64] When Anny Thackeray married on 2 August 1877, Julia would soon change her mind, and it was a proposal to install a German housekeeper, Fräulein Klappert, that brought the matter to a head, for both realised this would separate them.

[64][65] On 5 January 1878, Julia Duckworth and Leslie Stephen became engaged, and on 26 March they were married at Kensington Church, although she spent much of the period in between nursing her uncle, Henry Prinsep, at Watts's house in Freshwater, till he died on 11 February.

After spending several weeks visiting her sister, Virginia, at Eastnor Castle, Leslie and his seven-year-old daughter Laura moved next door to Julia's house at 13 (22) Hyde Park Gate (see image), where she continued to live for the rest of her life, and the family till her husband's death in 1904.

[85] Vanessa Bell's 1892 portrait of her sister and parents in the Library at Talland House (see image 5, below) was one of the family's favourites, and was written about lovingly in Leslie Stephen's memoir.

[95] In both London and Cornwall, Julia was perpetually entertaining, and was notorious for her manipulation of her guests' lives, constantly matchmaking in the belief everyone should be married, the domestic equivalence of her philanthropy.

In To The Lighthouse (1927)[93] the artist, Lily Briscoe, attempts to paint Mrs Ramsay, a complex character based on Julia Stephen, and repeatedly comments on the fact that she was "astonishingly beautiful".

She recalls trying to recapture "the clear round voice, or the sight of the beautiful figure, so upright and distinct, in its long shabby cloak, with the head held at a certain angle, so that the eye looked straight out at you".

[127] Julia dealt with her husband's depressive moods and his need for attention, which created resentment in her children, boosted his self-confidence, nursed her parents in their final illness, and had many commitments outside the home that would eventually wear her down.

[138][77] Julia's grandson, Quentin Bell (1910–1996) describes her as saintly, with a certain gravitas derived from sorrow, playful and tender with her children, sympathetic to the poor and sick or otherwise afflicted, and always called upon at times of need as a ministering angel.

Julia's legacy is the image Cameron portrayed in her earlier days, the fragile ethereal figure with large soulful eyes and long wild hair.

[40] Here Cameron frames the bust with emphatic side lighting that accentuates the tautness in the swanlike neck and the strength in the head,[157] indicating heroism and stateliness as befits a girl on the verge of matrimony.

She published a letter of protest on behalf of the inmates at St George's Union Workhouse in Fulham "for giving in to the temperance movement and cutting off the half-pint of beer".

The novelist Mary Ward (1851–1920) and the Oxford Liberal set collected the names of the most prominent intellectual aristocracy, including Julia's friend Octavia Hill (1838–1912), and nearly a hundred other women to sign a petition "An Appeal Against Female Suffrage" in Nineteenth Century in June of that year.

This earned her a rebuke from George Meredith, writing facetiously "for it would be to accuse you of the fatuousness of a Liberal Unionist to charge the true Mrs Leslie with this irrational obstructiveness", pretending that the signature must belong to another woman of the same name.

She defended the hierarchical system of the live-in servants, the need to keep a constant watch over them, and believed a "strong bond" existed between the mistress of the house and those who serve.

They have power to think as well, and they will not weaken their power of helping and loving by fearlessly owning their ignorance when they should be convinced of it ... Women do not stand on the same ground as men with regard to work, though we are far from allowing that our work is lower or less important than theirs, but we ought and do claim the same equality of morals ... man and woman have equal rights and, while crediting men with courage and sincerity, do not let us deny these qualities to each other.Julia Stephen was the mother of Bloomsbury.

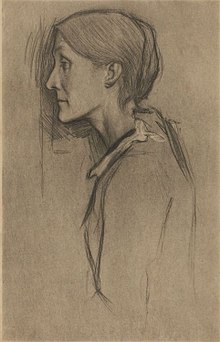

[160] George Watt's portrait of Julia (1875), originally hung in Leslie Stephen's study at Hyde Park Gate,[198] later it was in Duncan Grant's studio at 22 Fitzroy Square for some time, and then at Vanessa Bell's Charleston Farmhouse in Sussex,[199] where it still hangs.

After Leslie Stephen's death in 1904, 22 Hyde Park Gate was sold and the children moved to 46 Gordon Square, Bloomsbury, where they hung 5 of these on the right hand side of the entrance hall.

[222] She describes how Woolf's modernism needs to be viewed in relationship to her ambivalence towards her Victorian mother, the centre of the former's female identity, and her voyage to her own sense of autonomy.