Julian of Norwich

During her lifetime, the city suffered the devastating effects of the Black Death of 1348–1350, the Peasants' Revolt (which affected large parts of England in 1381), and the suppression of the Lollards.

Julian's writings emerged from obscurity in 1901 when a manuscript in the British Museum was transcribed and published with notes by Grace Warrack; many translations have been made since.

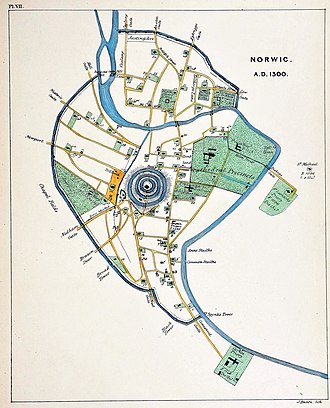

The English city of Norwich, where Julian probably lived all her life, was second in importance to London during the 13th and 14th centuries, and the centre of the country's primary region for agriculture and trade.

[5][note 2] During her lifetime, the Black Death reached Norwich; the disease may have killed over half the population of the city, and returned in subsequent outbreaks up to 1387.

Henry le Despenser, the Bishop of Norwich, executed Litster after the peasant army was defeated at the Battle of North Walsham.

[5] Norwich may have been one of the most religious cities in Europe at that time, with its cathedral, friaries, churches and recluses' cells dominating both the landscape and the lives of its citizens.

The few scant comments she provided about herself are contained in her writings, later published in a book commonly known as Revelations of Divine Love, a title first used in 1670.

[25] Julian's revelations seem to be the first important example of a vision by an Englishwoman for 200 years, in contrast with the Continent, where "a golden age of women's mysticism"[26] occurred during the 13th and 14th centuries.

[19] According to several commentators, including Santha Bhattacharji in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Julian's discussion of the maternal nature of God suggests that she knew of motherhood from her own experience of bringing up children.

[32] Kenneth Leech and Sister Benedicta Ward, the joint authors of Julian Reconsidered (1988), concluded that she was a young widowed mother and never a nun.

[11] Living in her cell, she would have played an important part within her community, devoting herself to a life of prayer to complement the clergy in their primary function as protectors of souls.

[36] During the ceremony, psalms from the Office of the Dead would have been sung for Julian (as if it were her funeral), and at some point she would have been led to her cell door and into the room beyond.

[44] According to one edition of the Cambridge Medieval History, it is possible that she met the English mystic Walter Hilton, who died when Julian was in her fifties, and who may have influenced her writings in a small way.

[24][47] In 14th century England, when women were generally barred from high status positions, their knowledge of Latin would have been limited, and it is more likely that they read and wrote in English.

[41] The historian Janina Ramirez has suggested that by choosing to write in her vernacular language, a precedent set by other medieval writers, Julian was "attempting to express the inexpressible" in the best way possible.

[50] Julian's writings were largely unknown until 1670, when they were published under the title XVI Revelations of Divine Love, shewed to a devout servant of Our Lord, called Mother Juliana, an Anchorete of Norwich: Who lived in the Dayes of King Edward the Third by Serenus de Cressy, a confessor for the English nuns at Cambrai.

It became still better known after the publication of Grace Warrack's 1901 edition, which included modernised language, as well as, according to the author Georgia Ronan Crampton, a "sympathetic informed introduction".

[59][60] After disappearing from view for 150 years, it was found in 1910, in a collection of contemplative medieval texts bought by the British Museum,[61] and was published by the Reverend Dundas Harford in 1911.

[66] For the theologian Denys Turner the core issue Julian addresses in Revelations of Divine Love is "the problem of sin".

[67][68] Julian lived in a time of turmoil, but her theology was optimistic and spoke of God's omnibenevolence and love in terms of joy and compassion.

[72] In her fourteenth revelation, Julian writes of the Trinity in domestic terms, comparing Jesus to a mother who is wise, loving and merciful.

"[69] Pope Francis also mentions her in his encyclical letter Dilexit nos as one of a number of "holy women" who have "spoken of resting in the heart of the Lord as the source of life and interior peace".

[14] St Julian's Church, located off King Street in the south of Norwich city centre, holds regular services.

[90] The building, which has a round tower, is one of the 31 parish churches from a total of 58 that once existed in Norwich during the Middle Ages,[91] of which 36 had an anchorite cell.

[96][note 5] The church underwent further restoration during the first half of the 20th century,[98] but was destroyed during the Norwich Blitz of June 1942 when the tower received a direct hit.

[99] The Catechism of the Catholic Church quotes from Revelations of Divine Love in its explanation of how God can draw a greater good, even from evil.

[100] The poet T. S. Eliot incorporated "All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of thing shall be well" three times into his poem "Little Gidding", the fourth of his Four Quartets (1943), as well as Julian's "the ground of our beseeching".

The celebration included concerts, talks, and free events held throughout the city, with the stated aim of encouraging people "to learn about Julian and her artistic, historical and theological significance".

[111] The Lady Julian Bridge, crossing the River Wensum and linking King Street and the Riverside Walk close to Norwich railway station, was named in honour of the anchoress.

An example of a swing bridge, built to allow larger vessels to approach a basin further upstream, it was designed by the Mott MacDonald Group and completed in 2009.