Julius Martov

Martov briefly enrolled at Saint Petersburg Imperial University, but was later expelled and exiled to Vilna, where he developed influential ideas on worker agitation.

Following the October Revolution, in which the Bolsheviks came to power, Martov advocated an "all-socialist" coalition government, but found himself politically marginalised.

He continued to lead the Mensheviks and denounced the Soviet government's repressive measures during the civil war, such as the Red Terror, while supporting the struggle against the Whites.

[2] In his teens, he admired the Narodniks, but the famine crisis made him a Marxist: "It suddenly became clear to me how superficial and groundless the whole of my revolutionism had been until then, and how my subjective political romanticism was dwarfed before the philosophical and sociological heights of Marxism".

That Autumn he enrolled at St Petersburg University, joined a Marxist group organized by Alexander Potresov, and was expelled, rearrested [Dec.], and held until May 1893.

[6] In 1893, Martov edited and wrote the preface to the book On Agitation, written by the Vilno Social Democrat, Arkady Kremer, which explained the strategy involving mass agitation and participating in Jewish strikes in the work, and which they smuggled into St. Petersburg in 1894 [7] The plan detailed that workers were to see a need for broader political campaigning through participating in strikes, led by the Social Democrats as trade unions were banned under the Tsarist regime.

[6] However, Martov would eventually have a critical parallel role with Lenin in the opposition to the Bund as they would not recognize them as an autonomous section within the RSDLP.

[9][6] Martov returned to St Petersburg in October 1895, and helped to form the League of Struggle for the Emancipation of the Working Class, in which Lenin was a dominant figure.

[11] When his term of exile ended, he joined Lenin in Pskov, where together they planned to go abroad and launch a newspaper as a way of organising the scattered Marxist movement into a centrally run political party.

[13][14] Initially, Lenin and Martov were allies in disputes within the six member editorial board, on which Georgi Plekhanov, the founder of Russian Marxism, had the casting vote.

[17] After Iskra moved again, to Geneva, in March 1903, Martov clashed with Lenin as one of the Marxists who wanted Nikolay Bauman expelled from the party on moral grounds.

He advocated the joining of a network of organisations, trade unions, cooperatives, village councils and soviets, to harass the bourgeois government until the economic and social conditions made it possible for a socialist revolution to take place.

At the 27th session, Lenin and Martov were again on the same side during an argument over whether the Bund should be recognised as an autonomous branch of the RSDLP, representing Jewish workers.

The two 'economist' delegates, Alexander Martynov and Vladimir Makhnovets also walked out, depriving Martov of seven votes, and giving Lenin's supporters a majority.

At the end of the Congress, there was a highly emotive dispute over the future composition of the editorial board of Iskra on which Lenin proposed to exclude the three least active editors, Zasulich, Pavel Axelrod, and Alexander Potresov.

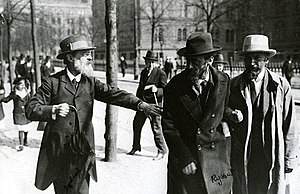

Martov was described as being "too good an intellectual to be a successful politician", as he often was held back by his integrity, and "philosophical approach" to matters of politics.

His outward appearance was far from attractive, but as soon as he began a fervent speech all these outer faults seemed to vanish, and what remained was his colossal knowledge, his sharp mind, and his fanatical devotion to the cause of the working class.

[32]Trotsky, who initially supported Martov against Lenin, later described him as "one of the most talented men I have ever come across" but added: "The man's misfortune was that fate made him a politician in a time of revolution without endowing him with the necessary resources of will power.

He strongly criticized those Mensheviks such as Irakli Tsereteli and Fedor Dan who, as members of the Russian government, supported the war effort.

However, at a conference held on 18 June 1917, he failed to gain the support of the delegates for a policy of immediate peace negotiations with the Central Powers.

He was unable to enter into an alliance with his rival Lenin to form a coalition in 1917, despite this being the "logical outcome" according to the majority of his left wing supporters in the Menshevik faction.

[41] This is best exemplified by Trotsky's comment to him and other party members as they left the first meeting of the council of Soviets after 25 October 1917 in disgust at the way in which the Bolsheviks had seized political power: "You are pitiful isolated individuals; you are bankrupts; your role is played out.

He paused at the exit, seeing a young Bolshevik worker wearing a black shirt with a broad leather belt, standing in the shadow of the portico.

Martov stopped, and with a characteristic movement, tossed up his head to emphasize his reply: "One day you will understand the crime in which you are taking part".

Later, when a factory section chose Martov as their delegate ahead of Lenin in a Soviet election, it found its supplies reduced soon afterwards.

In one of his newspaper articles, in 1918, he argued that Stalin was unfit to hold a high position in the communist party, alleging that he had been expelled from the RSDLP for involvement in the 1907 'expropriations'.

Martov had not intended to stay in Germany indefinitely, and only did so after the Mensheviks were outlawed in March 1921, following the Tenth Congress of the ruling Communist Party.

Before his fatal illness, he launched the newspaper Socialist Courier, which remained the publication of the Mensheviks in exile in Berlin, Paris, and eventually New York until the last of them had died.