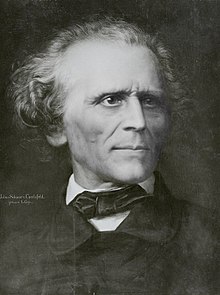

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld

The second period of Schnorr's artistic output began in 1825, when he left Rome, settled in Munich, entered the service of Ludwig I of Bavaria, and transplanted to Germany the art of wall-painting which he had learned in Italy.

He showed himself qualified as a sort of poet-painter to the Bavarian court; he organized a staff of trained executants, and covered five halls in the new palace – the "Residenz" – with frescoes illustrating the Nibelungenlied.

This however was rejected by Ludwig, leaving Schnorr to complain that he was left with the task of painting a mere "newspaper report of the Middle Ages" ("Zeitungsartikel des Mittelalters").

[8] The Picture Bible illustrations were often complex and cluttered; some critics found them lacking in harmony of line and symmetry, judging them to be inferior to equivalent work produced by Raphael.

[3] Schnorr's biblical drawings and cartoons for frescoes formed a natural prelude to designs for church windows, and his renown in Germany secured commissions in Great Britain.

The opposing party, however, claimed for these modern revivals "the union of the severe and excellent drawing of early Florentine oil-paintings with the colouring and arrangement of the glass-paintings of the latter half of the 16th century.

[9] In August 2016, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., returned a drawing in its collection, A Branch with Shriveled Leaves (1817) by Schnorr, to the heirs of Dr. Marianne Schmidl (1890–1942), an Austrian ethnologist who was murdered in the Holocaust.