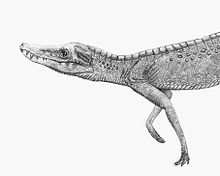

Junggarsuchus

The generic name of Junggarsuchus comes from the Junggar Basin (the anglicization of Dzungar),[4] where the fossil was found, and the Greek word "souchos" meaning crocodile.

[2] Junggarsuchus was found in the upper part of the Lower Member of the Shishugou Formation in Xinjiang, China at the Wucaiwan locality.

[2][5] The type and only specimen was described in 2004 by James Clark, Xu Xing, Catherine Forester, and Yuan Wang in Nature,[2] but it did not receive a full osteological description until 2022 when Alexander Ruebenstahl, Michael Klein, and Yi Hongyu published a monograph along with two of the original describers James Clark and Xu Xing.

[3] The skull of the holotype was transported from the Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, where it was initially reposited, to George Washington University, where it was studied and comprehensively re-described by Ruebenstahl and colleagues using modern CT imaging technology.

[3] In their initial description of the skull, Clark and colleagues noted that there was very little cranial kinesis and there were attachment sites for very powerful jaw muscles, which are derived traits found in modern crocodilians.

[2] With regard to the post-cranial skeleton, they noted that the spine of the holotype probably had very low vertical mobility across its length and it was mostly adapted for lateral motion, consistent with modern crocodilians.

The lateral surface of the angular bone has extensive attachment sites for jaw musculature, which is seen in some crown crocodilians, but not in other intermediate forms.

[3] Poor preservation of the pterygoid of the holotype also makes it difficult to infer the exact degree of pneumaticity or to speculate with regard to any of its possible functions.

The semicircular canal is tall and narrow, unlike in aquatic crocodilians, which is believed to have aided the animal in the orientation of the head and the gaze.

Based on CT data, Ruebenstahl and colleagues suggest that it is likely that the surangular is short in the jaw of Junggarsuchus and does not have significant contact with the angular.

Characteristics of the spine including the zygapophyses are suggestive of a much more flexible overall range of motion that most modern crocodiles lack completely.

Most of the close relatives of Junggarsuchus suich as Dibothrosuchus,[12] Terrestrisuchus,[13] and Dromicosuchus[14] are similarly gracile and adapted for fast terrestrial movement.

[2] Gracilisuchidae Rauisuchia Erpetosuchidae Pseudhesperosuchus Hesperosuchus Kayentasuchus Dromicosuchus Litargosuchus Sphenosuchus Junggarsuchus In 2017, Juan Martin Leardi and colleagues redescribed the closely related taxon, Macelognathus which had originally been described by O. C. Marsh in 1884 as a species of dinosaur.

Erpetosuchus Pseudhesperosuchus Trialestes Litargosuchus Hesperosuchus Dromicosuchus Kayentasuchus Sphenosuchus Junggarsuchus Almadasuchus Macelognathus Hemiprotosuchus Orthosuchus Sichuanosuchus Zosuchus In their re-description, Ruebenstahl and colleagues recovered a new clade, Solidocrania, meaning "solid skulls", in reference to the lack of cranial kinesis.

[3] Carnufex Hesperosuchus Trialestes Pseudhesperosuchus Kayentasuchus Dromicosuchus Redondavenator Litargosuchus Sphenosuchus Phyllodontosuchus Junggarsuchus Macelognathus Almadasuchus Orthosuchus Hemiprotosuchus

[3] The authors also noted that Hsisosuchus, generally considered to be basal to the ziphosuchian-neosuchian split, may actually be more closely related to ziphosuchians.

[2][3][18] Ruebenstahl and colleagues state that this finding implies that there is a 50 million-year-long ghost lineage of solidocranian taxa that stretches back into the Triassic.

[3] In 2023, Emily Lessner, Kathleen Dollman, James Clark, Xu Xing, and Casey Holliday performed an analysis of pseudosuchian facial nerves using skull material from over 20 different taxa including Junggarsuchus.

One possible explanation for this apparent discrepancy that the authors suggest is that earlier-diverging terrestrial crocodylomorphs may have exhibited a feeding ecology that included foraging on or near the ground for prey.

Junggarsuchus is a notable outlier in this trend because the inferred density of these nerves is much lower than in comparable taxa such as Macelognathus and Litargosuchus.

[20][21][22] Similarly, although not as strikingly, the teeth of Macelognathus are non-serrated on the crowns and their mandibular symphysis is entirely toothless, which has been interpreted as an adaptation for herbivory.

[15] There is no direct evidence to indicate exactly what the diet of Junggarsuchus may have consisted of, but given its size and dentition, most authors have stated that the most reasonable assumption is that it was a pursuit predator of small vertebrate prey.

[3][11] Furthermore, the overall shape of the skull and the ratio of its height to width (i.e. its "flatness") has been shown to be more similar to modern crocodilians than it is to contemporary crocodylomorphs.

[23] In total, the indirect evidence seems to indicate the Junggarsuchus most likely fed on small animals like primitive mammals, squamates, and possibly hatchling dinosaurs.

[25] This region is inland and arid today, but in the Late Jurassic, it formed a coastal basin on the northern shores of the Tethys Ocean.

[26] This pattern of rainfall led to the prominence of seasonal mires, possibly exacerbated by substrate liquefaction by the footfalls of massive sauropods which created "death pits" that trapped and buried small animals.