The Jungle Book

Most stories are set in a forest in India; one place mentioned repeatedly is "Seeonee" (Seoni), in the central state of Madhya Pradesh.

[3] There is evidence that Kipling wrote the collection of stories for his daughter, Josephine (who died from pneumonia in 1899, aged 6); a first-edition copy of the book—including a handwritten note by the author to his young daughter—was discovered at the National Trust's Wimpole Hall, Cambridgeshire, in 2010.

The Kipling Society notes that "Seeonee" (Seoni, in the central Indian state of Madhya Pradesh) is mentioned several times; that the "cold lairs" must be in the jungled hills of Chittorgarh; and that the first Mowgli story, "In the Rukh", is set in a forest reserve somewhere in North India, south of Simla.

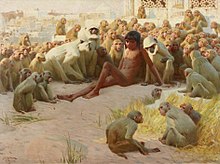

The early editions were illustrated with drawings in the text by John Lockwood Kipling (Rudyard's father), and the American artists W. H. Drake and Paul Frenzeny.

In his view, the enemy, Shere Khan, represents the "malevolent would-be foster-parent" who Mowgli in the end outwits and destroys, just as Kipling as a boy had to face Mrs Holloway in place of his parents.

[25] The historian of India Philip Mason similarly emphasises the Mowgli myth, where the fostered hero, "the odd man out among wolves and men alike", eventually triumphs over his enemies.

[25] Sandra Kemp observed that the law may be highly codified, but that the energies are also lawless, embodying the part of human nature which is "floating, irresponsible and self-absorbed".

[25] The novelist and critic Angus Wilson noted that Kipling's law of the jungle was "far from Darwinian", since no attacks were allowed at the water-hole when in drought.

[30] The academic Jan Montefiore commented on the book's balance of law and freedom that "you don't need to invoke Jacqueline Rose on the adult's dream of the child's innocence or Perry Nodelman's theory of children's literature colonising its readers' minds with a double fantasy of the child as both noble savage and embryo good citizen, to see that the Jungle Books .. give their readers a vicarious experience of adventure both as freedom and as service to a just State".

[32] The academic Jopi Nyman argued in 2001 that the book formed part of the construction of "colonial English national identity"[33] within Kipling's "imperial project".

[33] In Nyman's view, nation, race and class are mapped out in the stories, contributing to "an imagining of Englishness" as a site of power and racial superiority.

[33] Swati Singh, in his Secret History of the Jungle Book, notes that the tone is like that of Indian folklore, fable-like, and that critics have speculated that the Kipling may have heard similar stories from his Hindu bearer and his Portuguese ayah (nanny) during his childhood in India.

This use of the book's universe was approved by Kipling at the request of Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Scouting movement, who had originally asked for the author's permission for the use of the Memory Game from Kim in his scheme to develop the morale and fitness of working-class youths in cities.

Akela, the head wolf in The Jungle Book, has become a senior figure in the movement; the name is traditionally adopted by the leader of each Cub Scout pack.

In literature, Robert Heinlein wrote the Hugo Award-winning science fiction novel, Stranger in a Strange Land (1961), when his wife, Virginia, suggested a new version of The Jungle Book, but with a child raised by Martians instead of wolves.

[38] It was directed by Chris Wallis with Nisha K. Nayar as Mowgli, Eartha Kitt as Kaa, Freddie Jones as Baloo, and Jonathan Hyde as Bagheera.

[43] Many films have been based on one or another of Kipling's stories, including Elephant Boy (1937),[44] Chuck Jones's made for-TV cartoons Rikki-Tikki-Tavi (1975),[45] The White Seal (1975),[46] and Mowgli's Brothers (1976).

[53] In 2021 BBC Radio 4 broadcast an adaptation by Ayeesha Menon which resets the story as a "gangland coming-of-age fable" in modern India.