Juno Beach

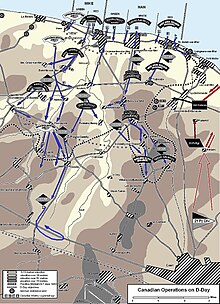

The objectives of the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division on D-Day were to cut the Caen-Bayeux road, seize the Carpiquet airport west of Caen, and form a link between the two British beaches on either flank.

The landings encountered heavy resistance from the German 716th Division; the preliminary bombardment proved less effective than had been hoped, and rough weather forced the first wave to be delayed until 07:35.

[5] Following the Anglo-American victory against Field Marshal Erwin Rommel in North Africa in May 1943, British, American and Canadian troops invaded Sicily in July 1943, followed by Italy in September.

[7] After gaining valuable experience in amphibious assaults and inland fighting, Allied planners returned to the plans to invade Northern France, now postponed to 1944.

[8] Under the direction of General Dwight D. Eisenhower (Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force) and Frederick Morgan, plans for the invasion of France coalesced as Operation Overlord.

With an initial target date of 1 May 1944, the infantry attack was conceived as a joint assault by five divisions transported by landing craft,[9] constituting the largest amphibious operation in military history.

[10] There were originally seventeen sectors along the Normandy coastline with codenames taken from one of the spelling alphabets of the time, from Able, west of Omaha, to Rodger on the east flank of the invasion area.

Juno, a 6 mi (9.7 km) stretch of shoreline between La Rivière to the west and Saint-Aubin to the east, was assigned to the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division (3rd CID), commanded by Major-General Rod Keller.

[19] Under the command of Field Marshals Erwin Rommel and Gerd von Rundstedt, the defences of the Atlantic Wall – a line of coastal gun emplacements, machine-gun nests, minefields and beach obstacles along the French coast – were increased; in the first six months of 1944, the Germans laid 1,200,000 long tons (1,200,000 t) of steel and 17,300,000 cu yd (13,200,000 m3) of concrete.

By nightfall of D-Day, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division was slated to have captured the high ground west of Caen, the Bayeux–Caen railway line, and the seaside towns of Courseulles, Bernières, Saint-Aubin and Bény-sur-Mer.

The naval gunfire proved more effective than the aerial bombardment; the battery at Longues was the only one to return fire, and was quickly destroyed by the light cruiser HMS Ajax.

[51] Though the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade was scheduled to land on Mike Sector at 07:35, rough seas and poor craft co-ordination pushed this time back by ten minutes.

[58] The bombardment had failed to destroy the emplacement and heavy machine guns inflicted many casualties on the company; one LCA reported six men killed within seconds of lowering the ramps.

[66] "B" Company came ashore directly in front of the main resistance nests, 200 yards east of their intended landing zone, subjecting them to heavy mortar and machine-gun fire.

By 08:10, Sherman tanks of the Fort Garry Horse and AVRE of the 80th Assault Squadron, Royal Engineers, had landed at Nan Red and begun to assist "B" Company in clearing the gun emplacement.

The reports coming in from the battalions already on Juno were mixed; Canadian military historian Terry Copp says that the North Shore was "proceeding according to plan", while the Chaudières were "making progress slowly".

[94] Having subdued German defences on the beach, the next task of the landed forces was to clear Juno of obstacles, debris and undetonated mines then establish the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division's headquarters in Bernières.

[97] "A" and "C" Companies of the Royal Winnipegs moved off the beach, cut through the walls of barbed wire behind the German bunkers, pushed through Vaux and Graye-sur-Mer, and began to advance towards St. Croix and Banville.

[f] The Queen's Own Rifles' "C" Company was pinned down at the edge of Bernières by sniper-fire, and could not cross the open fields behind the town; their armoured support was also stopped by heavy antitank fire coming from Beny-sur-Mer.

[117] These units had the important objective of bridging the 5 mi (8.0 km) gap between the landing zones at Juno and Sword, which would allow for a continuous Anglo-Canadian front by the end of the first day.

"C" Company's advance on Basly was even further hindered by the proximity of the combat; the fighting occurred at such close range that the 14th Field Artillery would not provide fire support for fear of friendly-fire casualties.

Once St. Croix and Banville were cleared, the Canadian Scots pushed south to Colombiers, reinforced the platoons that had captured the bridge across the Seulles earlier in the day, and moved towards the Creully–Caen road.

[128] The Regina Rifles had been slow to advance from Courseulles on account of the heavy casualties taken securing the village; the 1st Hussars' "B" Squadron was in a similar position, with only half its fighting strength having made it off the beach.

Aside from a German staff-car and a machine-gun nest, the three Sherman tanks encountered virtually no resistance, advancing all the way to the Caen–Bayeux railway line and becoming the only unit on the whole of D-Day to reach its final objective.

[40] Chester Wilmot offers a different view, suggesting that "[the coastal guns] had been accurately bombed, but had survived because they were heavily protected by the concrete casemates Rommel had insisted upon".

[151] Terry Copp echoes this analysis, noting that "reasonable accuracy could not be obtained from the pitching decks of LCTs [by mounted artillery on the ships]"; the 13th Field Regiment's drenching fire fell on average 200 yards (180 m) past their targets.

Mark Zuehlke notes that "the Canadians ended the day ahead of either the US or British divisions despite the facts that they landed last (a delay of half an hour due to bad weather) and that only the Americans at Omaha faced more difficulty winning a toehold on the sand".

[66] Wilmot also places the blame with logistical difficulties of the landing, saying that "on the whole it was not so much the opposition in front as the congestion behind—on the beaches and in Bernières—that prevented the Canadians from reaching their final D-Day objective".

[160] Copp disagrees with Stacey's assessment, suggesting that such caution was not the result of poor planning but of the fact that "the British and Canadians fought the way they had been trained, moving forward to designated objectives in controlled bounds and digging in at the first sign of a counterattack".

He also disputes whether the capture of the final objectives would have been strategically intelligent, observing that "if 9th Brigade had reached Carpiquet and dug in, with artillery in position to offer support, the commander of the 26th Panzer Grenadiers might have followed orders and waited until a coordinated counterattack with other divisions had been organized.