Jury

A jury is a sworn body of people (jurors) convened to hear evidence, make findings of fact, and render an impartial verdict officially submitted to them by a court, or to set a penalty or judgment.

In Ireland and other countries in the past, the task of a grand jury was to determine whether the prosecutors had presented a true bill (one that described a crime and gave a plausible reason for accusing the named person).

[21] Juries, usually 6 or 12 men, were an "ancient institution" even then in some parts of England, at the same time as Members consisted of representatives of the basic units of local government—hundreds (an administrative sub-division of the shire, embracing several vills) and villages.

In modern justice systems, the law is considered "self-contained" and "distinct from other coercive forces, and perceived as separate from the political life of the community," but "all these barriers are absent in the context of classical Athens.

[31] In the late 18th century, English and colonial civil, criminal and grand juries played major roles in checking the power of the executive, the legislature and the judiciary.

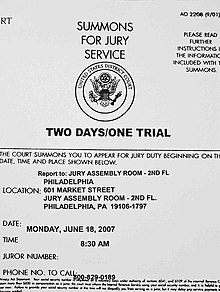

[2] In modern times, juries are often initially chosen randomly, usually from large databases identifying the eligible population of adult citizens residing in the court's jurisdictional area (e.g., identity cards, drivers' licenses, tax records, or similar systems), and summons are delivered by mail.

In 2009 a review by the Scottish Government regarding the possibility of reduction[39] led to the decision to retain 15 jurors, with the Cabinet Secretary for Justice stating that after extensive consultation, he had decided that Scotland had got it "uniquely right".

At this point the judge often will ask each prospective juror to answer a list of general questions such as name, occupation, education, family relationships, time conflicts for the anticipated length of the trial.

Juries are often instructed to avoid learning about the case from any source other than the trial (for example from media or the Internet) and not to conduct their own investigations (such as independently visiting a crime scene).

The collective knowledge and deliberate nature of juries are also given as reasons in their favor: Detailed interviews with jurors after they rendered verdicts in trials involving complex expert testimony have demonstrated careful and critical analysis.

This practice was required in all death penalty cases in Blakely v. Washington, 542 U.S. 296 (2004), where the Supreme Court ruled that allowing judges to make such findings unilaterally violates the Sixth Amendment right to a jury trial.

A similar Sixth Amendment argument in Apprendi v. New Jersey, 530 U.S. 466 (2000) resulted in the Supreme Court's expansion of the requirement to all criminal cases, holding that "any fact that increases the penalty for a crime beyond the prescribed statutory maximum must be submitted to a jury and proved beyond a reasonable doubt".

In a small number of U.S. jurisdictions, including the states of Tennessee[51] and Texas,[52] juries are charged both with the task of finding guilt or innocence as well assessing and fixing sentences.

[53][better source needed] Thus, although juries must render unanimous verdicts, in run-of-the-mill criminal trials they behave in practice as if they were operating using a majority rules voting system.

"[54] In the 17th and 18th centuries, there was a series of such cases, starting in 1670 with the trial of the Quaker William Penn which asserted the (de facto) right, or at least power, of a jury to render a verdict contrary to the facts or law.

Another example is the acquittal in 1989 of Michael Randle and Pat Pottle, who confessed in open court to charges of springing the Soviet spy George Blake from Wormwood Scrubs Prison and smuggling him to East Germany in 1966.

When capital punishment in Canada was abolished in 1976, as part of the same raft of reforms, the Criminal Code was also amended to grant juries the ability to recommend periods of parole ineligibility immediately following a guilty verdict in second-degree murder cases; however, these recommendations are usually ignored, based on the idea that judges are better-informed about relevant facts and sentencing jurisprudence and, unlike the jury, permitted to give reasons for their judgments.

[64] In Canada, a faint hope clause formerly allowed a jury to be empanelled to consider whether an offender's number of years of imprisonment without eligibility for parole ought to be reduced, but this was repealed in 2011.

[69] According to Simon (1980), jurors approach their responsibilities as decision makers much in the same way as a court judge: with great seriousness, a lawful mind, and a concern for consistency that is evidence-based.

By actively processing evidence, making inferences, using common sense and personal experiences to inform their decision-making, research has indicated that jurors are effective decision makers who seek thorough understanding, rather than passive, apathetic participants unfit to serve on a jury.

[70] Contemporary research has provided partial support for the proficiency of juries as decision makers due to taking their work seriously to get a fair outcome and by relying on the group to overcome individual biases.

[71] The thoroughness of the jury trial has also been praised for providing the public with important information that is often not released in alternative procedures like arbitration or adjudication by judges or administrative agencies.

[78] Burns further argues that interest groups have increasing influence over political branches, including judges, and that the jury was designed to resist the new Gilded Age-level concentration of power.

[83] Lastly, Burns argues the jury is a vote of confidence for democracy as the most democratic institution (at least in America) and one that demonstrates that it is possible to find common ground on difficult questions, especially when decisions must be unanimous.

[85] The Constitution of Brazil provides that only willful crimes against life, namely full or attempted murder, abortion, infanticide and suicide instigation, be judged by juries.

In each court district where a grand jury is required, a group of 16–23 citizens holds an inquiry on criminal complaints brought by the prosecutor to decide whether a trial is warranted (based on the standard that probable cause exists that a crime was committed), in which case an indictment is issued.

[122] Juryless trials under the inadequacy exception, dealing with terrorism or organised crime, are held in the Special Criminal Court, on application by the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP).

In 2008, the anti-state criminal cases (treason, espionage, armed rebellion, sabotage, mass riot, creating an illegal paramilitary group, forcible seizure of power, terrorism) were removed from the jurisdiction of the jury trial.

Article 2 of the Spanish Constitution of 1837 while proclamating the freedom of the people to publicate written contents without previous censorship according to the laws also provided that "press crimes" could only be tried by juries.

The provision is arguably somewhat vague: "Article 125 – Citizens may engage in popular action and participate in the administration of justice through the institution of the Jury, in the manner and with respect to those criminal trials as may be determined by law, as well as in customary and traditional courts."