Magnitsky legislation

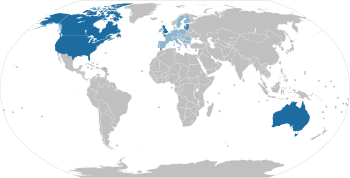

Magnitsky legislation refers to laws providing for governmental sanctions against foreign individuals who have committed human rights abuses or been involved in significant corruption.

[4] The original Magnitsky Act of 2012 was expanded in 2016 into a more general law authorizing the US government to sanction those found to be human rights offenders or those involved in significant corruption, to freeze their assets, and to ban them from entering the US.

[10] As such, the Act is perceived as damaging relations with Russia, especially with earlier warnings from the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs that the law would be a "blatantly unfriendly step.

[23][24][25][26] On 9 December 2019, the EU Foreign Affairs and Security Policy High Representative Josep Borrell, who is the chief co-ordinator and representative of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) within the EU, announced that all member states had "agreed to launch the preparatory work for a global sanctions regime to address serious human rights violations, which will be the European Union equivalent of the so-called Magnitsky Act of the United States.

Entitled to submit proposals for sanctions implementations, review or amendment are each of the member states and also the High Representative of the EU for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

The law, which was passed unanimously in the Estonian Parliament, states that it entitles Estonia to disallow entry to people if, among other things, "there is information or good reason to believe" that they took part in activities which resulted in the "death or serious damage to health of a person.

[39] On 8 February 2018, the Parliament of Latvia (Saeima) accepted attachment of a law of sanctions, inspired by the Sergei Magnitsky case, to ban foreigners deemed guilty of human rights abuses from entering the country.

[45][46] In 2020, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade was asked about the possibility of Australia stopping the issuance of visas to Huawei Technologies employees for their complicity in China's human-rights violations, including in Xinjiang.

[47] Meanwhile, Australia was urged by the Bill Browder, who lobbied the U.S. Magnitsky Act into Congress, to pass its own Magnitsky law or "risks becoming "a magnet for dirty money" from abusers and kleptocrats across the globe"[48] In December 2020, the Joint Standing Committee tabled its report and recommended that the Australian Government "enact stand alone targeted sanctions legislation to address human rights violations and corruption, similar to the United States' Magnitsky Act 2012 which provides for sanctions targeted at individuals rather than existing sanctions regimes which are more often directed at states".

[45] In August 2021, the Australian Government announced that it would adopt a sanctions law similar to the U.S. Magnitsky Act that allows targeted financial sanctions and travel bans against individuals for egregious acts of international concern that could include the proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, gross human rights violations, malicious cyber activity, and serious corruption.

In July 2018, a Magnitsky bill was introduced into the Moldovan parliament,[60] mandating sanctions against individuals who "have committed or contributed to human rights violations and particularly serious acts of corruption that are harmful to international political and economic stability.