Franz Kafka

After working as a travelling sales representative, he eventually became a fashion retailer who employed up to 15 people and used the image of a jackdaw (kavka in Czech, pronounced and colloquially written as kafka) as his business logo.

[36] Among Kafka's friends were the journalist Felix Weltsch, who studied philosophy, the actor Yitzchak Lowy who came from an orthodox Hasidic Warsaw family, and the writers Ludwig Winder, Oskar Baum and Franz Werfel.

Two weeks later, he found employment more amenable to writing when he joined the Worker's Accident Insurance Institute for the Kingdom of Bohemia (Úrazová pojišťovna dělnická pro Čechy v Praze).

The job involved investigating and assessing compensation for personal injury to industrial workers; accidents such as lost fingers or limbs were commonplace, owing to poor work safety policies at the time.

Kafka was rapidly promoted and his duties included processing and investigating compensation claims, writing reports, and handling appeals from businessmen who thought their firms had been placed in too high a risk category, which cost them more in insurance premiums.

[72][73]Shortly after this meeting, Kafka wrote the story "Das Urteil" ("The Judgment") in only one night and in a productive period worked on Der Verschollene (The Man Who Disappeared) and Die Verwandlung (The Metamorphosis).

[7] Stach and Brod state that during the time that Kafka knew Felice Bauer, he had an affair with a friend of hers, Margarethe "Grete" Bloch,[80] a Jewish woman from Berlin.

[85] Kafka was diagnosed with tuberculosis in August 1917 and moved for a few months to the Bohemian village of Zürau (Siřem in Czech), where his sister Ottla worked on the farm of her brother-in-law Karl Hermann.

[17] His two brothers, Georg and Heinrich, died in infancy; his three sisters, Gabriele ("Elli") (September 22, 1889 – fall of 1942), Valerie ("Valli") (1890–1942) and Ottilie ("Ottla") (1892–1943), are believed to have been murdered in the Holocaust of the Second World War.

[106] Kafka's letters and unexpurgated diaries reveal repressed homoerotic desires, including an infatuation with novelist Franz Werfel and fascination with the work of Hans Blüher on male bonding.

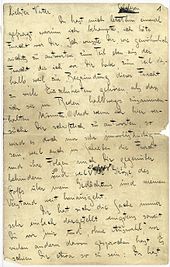

[114] His anguish can be seen in this diary entry from 21 June 1913:[115] and in Zürau Aphorism number 50: Italian medical researchers Alessia Coralli and Antonio Perciaccante have posited in a 2016 article that Kafka may have had borderline personality disorder with co-occurring psychophysiological insomnia.

[119] Joan Lachkar interpreted Die Verwandlung as "a vivid depiction of the borderline personality" and described the story as "model for Kafka's own abandonment fears, anxiety, depression, and parasitic dependency needs.

[143] Pavel Eisner, one of Kafka's first translators, interprets Der Process (The Trial) as the embodiment of the "triple dimension of Jewish existence in Prague ... his protagonist Josef K. is (symbolically) arrested by a German (Rabensteiner), a Czech (Kullich), and a Jew (Kaminer).

Brod noted the similarity in names of the main character and his fictional fiancée, Georg Bendemann and Frieda Brandenfeld, to Franz Kafka and Felice Bauer.

[173] His last story, "Josefine, die Sängerin oder Das Volk der Mäuse" ("Josephine the Singer, or the Mouse Folk"), also deals with the relationship between an artist and his audience.

[177] More explicitly humorous and slightly more realistic than most of Kafka's works, the novel shares the motif of an oppressive and intangible system putting the protagonist repeatedly in bizarre situations.

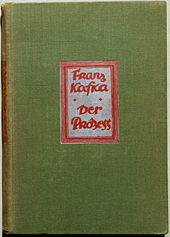

[180] In 1914 Kafka began the novel Der Process (The Trial),[163] the story of a man arrested and prosecuted by a remote, inaccessible authority, with the nature of his crime revealed neither to him nor to the reader.

[182] Michiko Kakutani notes in a review for The New York Times that Kafka's letters have the "earmarks of his fiction: the same nervous attention to minute particulars; the same paranoid awareness of shifting balances of power; the same atmosphere of emotional suffocation—combined, surprisingly enough, with moments of boyish ardour and delight.

[183] Dark and at times surreal, the novel is focused on alienation, bureaucracy, the seemingly endless frustrations of man's attempts to stand against the system, and the futile and hopeless pursuit of an unattainable goal.

Hartmut M. Rastalsky noted in his thesis: "Like dreams, his texts combine precise 'realistic' detail with absurdity, careful observation and reasoning on the part of the protagonists with inexplicable obliviousness and carelessness.

", and added in the personal copy given to his friend "So wie es hier schon gedruckt ist, für meinen liebsten Max—Franz K." ("As it is already printed here, for my dearest Max").

[204][205] Subsequently, Pasley headed a team (including Gerhard Neumann, Jost Schillemeit and Jürgen Born) which reconstructed the German novels; S. Fischer Verlag republished them.

[232] Critics who support this absurdist interpretation cite instances where Kafka describes himself in conflict with an absurd universe, such as the following entry from his diary: Enclosed in my own four walls, I found myself as an immigrant imprisoned in a foreign country;...

[245] Published in 1961 by Schocken Books, Parables and Paradoxes presented in a bilingual edition by Nahum N. Glatzer selected writings,[246] drawn from notebooks, diaries, letters, short fictional works and the novel Der Process.

[250] An example is the first sentence of Kafka's The Metamorphosis, which is crucial to the setting and understanding of the entire story:[251] Als Gregor Samsa eines Morgens aus unruhigen Träumen erwachte, fand er sich in seinem Bett zu einem ungeheuren Ungeziefer verwandelt.

[261] Shimon Sandbank, a professor, literary critic, and writer, also identifies Kafka as having influenced Jorge Luis Borges, Albert Camus, Eugène Ionesco, J. M. Coetzee and Jean-Paul Sartre.

[269] Harold Bloom said "when he is most himself, Kafka gives us a continuous inventiveness and originality that rivals Dante and truly challenges Proust and Joyce as that of the dominant Western author of our century".

Kafkaesque elements often appear in existential works, but the term has transcended the literary realm to apply to real-life occurrences and situations that are incomprehensibly complex, bizarre, or illogical.

Films from other genres which have been similarly described include Roman Polanski's The Tenant (1976), Joseph Losey’s Monsieur Klein (1976)[303] and the Coen brothers' Barton Fink (1991).

[307] More accurately then, according to author Ben Marcus, paraphrased in "What it Means to be Kafkaesque" by Joe Fassler in The Atlantic, "Kafka's quintessential qualities are affecting use of language, a setting that straddles fantasy and reality, and a sense of striving even in the face of bleakness—hopelessly and full of hope.