Klezmer

[6][7] Among the European-born klezmers who popularized the genre in the United States in the 1910s and 1920s were Dave Tarras and Naftule Brandwein; they were followed by American-born musicians such as Max Epstein, Sid Beckerman and Ray Musiker.

[citation needed] The traditional style of playing klezmer music, including tone, typical cadences, and ornamentation, sets it apart from other genres.

[20][18] The usage of these ornaments was not random; the matters of "taste", self-expression, variation and restraint were and remain important elements of how to interpret the music.

They incorporate and elaborate the vocal melodies of Jewish religious practice, including khazones, davenen, and paraliturgical song, extending the range of human voice into the musical expression possible on instruments.

[21] Among those stylistic elements that are considered typically "Jewish" in klezmer music are those which are shared with cantorial or Hasidic vocal ornaments, including imitations of sighing or laughing.

[22] Various Yiddish terms were used for these vocal-like ornaments such as קרעכץ (Krekhts, "groan" or "moan"), קנײטש (kneytsh, "wrinkle" or "fold"), and קװעטש (kvetsh, "pressure" or "stress").

[18] In particular, the cadences which draw on religious Jewish music identify a piece more strongly as a klezmer tune, even if its broader structure was borrowed from a non-Jewish source.

In Eastern Europe, Klezmers did traditionally accompany the vocal stylings of the Badchen (wedding entertainer), although their performances were typically improvised couplets and the calling of ceremonies rather than songs.

The klezmer bands of the eighteenth and early nineteenth century were small, with roughly three to five musicians playing woodwind or string instruments.

[41] By the last decades of the century, in Ukraine, the orchestras had grown larger, averaging seven to twelve members, and incorporating brass instruments and up to twenty for a prestigious occasion.

[42]) In these larger orchestras, on top of the core instrumentation of strings and woodwinds, cornets, C clarinets, trombones, a contrabass, a large Turkish drum, and several extra violins.

[45][30] American klezmer as it developed in dancehalls and wedding banquets of the early twentieth century had a more complete orchestration not unlike those used in popular orchestras of the time.

[34] But it also incorporates elements of Baroque and Eastern European folk musics, making description based only on religious terminology incomplete.

[29][30][48] Beregovsky, who was writing in the Stalinist era and was constrained by having to downplay klezmer's religious aspects, did not use the terminology of synagogue modes, except in some early work in 1929.

[51][53] This approach dates back to Idelsohn in the early twentieth century, who was very familiar with Middle Eastern music, and has been developed in the past decade by Joshua Horowitz.

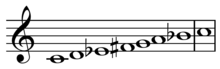

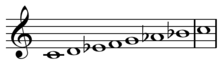

[25] Because there is no agreed-upon, complete system for describing modes in Klezmer music, this list is imperfect and may conflate concepts which some scholars view as separate.

The rise of Hasidic Judaism in the late eighteenth century and onwards also contributed to the development of klezmer, due to their emphasis on dancing and wordless melodies as a component of Jewish practice.

[68][69] The loosening of restrictions on Jews in the Russian Empire, and their newfound access to academic and conservatory training, created a class of scholars who began to reexamine and evaluate klezmer using modern techniques.

[30] Abraham Zevi Idelsohn was one such figure, who sought to find an ancient Middle Eastern origin for Jewish music in the diaspora.

[80] Some of them found work in restaurants, dance halls, union rallies, wine cellars, and other modern venues in places like New York's Lower East Side.

[85] The first of these was Abe Elenkrig, a barber and cornet player from a klezmer family in Ukraine whose 1913 recording Fon der Choope (From the Wedding) has been recognized by the Library of Congress.

[86][87][88] Among the European-born klezmers recording during that decade were some from the Ukrainian territory of the Russian Empire (Abe Elenkrig, Dave Tarras, Shloimke Beckerman, Joseph Frankel, and Israel J. Hochman), some from Austro-Hungarian Galicia (Naftule Brandwein, Harry Kandel and Berish Katz), and some from Romania (Abe Schwartz, Max Leibowitz, Max Yankowitz, Joseph Moskowitz).

[101] The 1980s saw a second wave of revival, as interest grew in more traditionally inspired performances with string instruments, largely with non-Jews of the United States and Germany.

Key performers in this style are Joel Rubin, Budowitz, Khevrisa, Di Naye Kapelye, Yale Strom, The Chicago Klezmer Ensemble, The Maxwell Street Klezmer Band, the violinists Alicia Svigals, Steven Greenman,[102] Cookie Segelstein and Elie Rosenblatt, flutist Adrianne Greenbaum, and tsimbl player Pete Rushefsky.

Starting in 2008, "The Other Europeans" project, funded by several EU cultural institutions,[104] spent a year doing intensive field research in the region of Moldavia under the leadership of Alan Bern and scholar Zev Feldman.

[106][107] While traditional performances may have been on the decline, many Jewish composers who had mainstream success, such as Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copland, continued to be influenced by the klezmeric idioms heard during their youth (as Gustav Mahler had been).

Dmitri Shostakovich in particular admired klezmer music for embracing both the ecstasy and the despair of human life, and quoted several melodies in his chamber masterpieces, the Piano Quintet in G minor, op.

Kaplan, making his art in the Soviet Union, was quite taken by the romantic images of the Klezmer in literature, and in particular in Sholem Aleichem's Stempenyu, and depicted them in rich detail.

[113] However, in nineteenth century works by writers such as Mendele Mocher Sforim and Sholem Aleichem they were also portrayed as great artists and virtuosos who delighted the masses.

[30] Klezmers also appeared in non-Jewish Eastern European literature, such as in the epic poem Pan Tadeusz, which depicted a character named Jankiel Cymbalist, or in the short stories of Leopold von Sacher-Masoch.