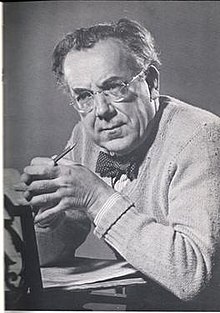

Karl Rankl

A pupil of the composers Schoenberg and Webern, he conducted at opera houses in Austria, Germany and Czechoslovakia until fleeing from the Nazis and taking refuge in England in 1939.

By 1951, performances under guest conductors, such as Erich Kleiber and Sir Thomas Beecham were overshadowing Rankl's work, and he resigned.

[4][5] Rankl's first professional post was as chorus master and répétiteur under Felix Weingartner at the Volksoper in Vienna in 1919, where he later became an assistant conductor.

[8] He moved back to Austria to head the opera at Graz in 1933,[1] and in 1937 he was appointed principal conductor of the Neues Deutsches Theater in Prague.

[9] In wartime Britain Rankl was unable to obtain a permit to work as a conductor until 1944, and he devoted much of his time to composition.

[13] He made a favourable impression; The Times praised his "boundless energy … clear-cut performance and with a strong feeling for the shapely line of a melody.

Rankl was on the verge of going to Australia in response to an invitation from the Australian Broadcasting Corporation to conduct a 13-week season of 20 concerts.

[17] Among those outraged by Rankl's appointment was Sir Thomas Beecham, who had been in control of Covent Garden for much of the period from 1910 to 1939, and was furious at being excluded under the new regime.

"[21] The company, headed by Edith Coates and including Dennis Noble, Grahame Clifford, David Franklin and Constance Shacklock, was warmly praised.

[21] In the next two operas presented by the company, Rankl was thought a little stolid in The Magic Flute, but was praised for "weaving Strauss's flexible rhythms" in Der Rosenkavalier.

[22] Rankl tackled the Italian repertoire, and new English works, winning praise for his Rigoletto, though with Peter Grimes he was compared to his disadvantage with the original conductor, Reginald Goodall.

[24] Despite the good notices for his early seasons, Rankl had to cope with a vociferous public campaign by Beecham against the very idea of establishing a company of British artists; Beecham maintained that the British could not sing opera, and had produced only half a dozen first rate operatic artists in the past 60 years.

[25] In the next three years, Rankl built the company up, reluctantly casting foreign stars when no suitable British singer could be found, and resisting attempts by Webster to invite eminent guest conductors.

[26] When Webster and the Covent Garden board insisted, Rankl took it badly that star conductors such as Erich Kleiber, Clemens Krauss and Beecham were brought into "his" opera house.

[27] In a biographical article in the Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, the critic Frank Howes wrote of Rankl: "By 1951 he had made the Covent Garden Company a going concern, but had also revealed, notably in his 1950 performances of the Ring, his limitations as a conductor – he was considered difficult with singers, orchestras and producers.

[31] He was never invited to conduct there again, and did not set foot in the building for another 14 years, until 1965 for the first night of Moses und Aron by his old teacher, Schoenberg; the conductor then was Georg Solti.