Karl Wilhelm Fricke

[2][3] From 1970 till 1994, he worked for (West) Germany's national radio station where he was influential as a political commentator and as the broadcaster's editor for "East-West affairs".

During the Nazi years he had worked in the little town of Hoym as the head of a press office and a "deputy propaganda chief" of the local Party Group.

Fricke's refusal to join the ruling party's youth wing left him with no opportunity formally to complete his secondary education.

Fricke later recalled the impact on him of Abenroth's monthly informal seminars at Wilhelmshaven where students sat and discussed the works of Socialism's pre-Stalin heroes such as Rosa Luxemburg and Leon Trotsky.

While he always maintained a reputation for well-researched and accurate reporting, the circumstances of his father's death were clearly no random misfortune: they profoundly strengthened his opposition to what he later described as a governmental structure politically predicated not on the democratically expressed will of the people but on "systematic injustice".

[1][6] Before completing his time at Wilhelmshaven Fricke had already begun his relocation to West Berlin, then the brittle front-line between intellectually incompatible competing power blocs.

In Berlin there was a rich stream of material for a free-lance political journalist: Fricke's career in print continued to progress, now complemented by excursions into radio-journalism.

Officers of the recently established East Germany Ministry for State Security considered that his published articles, which they studied in close detail, were deeply damaging to the German Democratic Republic.

[5] In the course of his researches Fricke came across a man called Kurt Maurer,[12] a formerly Communist fellow-journalist who had spent time in a concentration camp during the Nazi years, and then following the war been interned by the Soviets.

Also Maurer had somehow obtained access to a source of books in the German Democratic Republic which were helpful in the context of Fricke's journalistic investigations.

Returning to the living room he still felt unwell and asked Mrs Maurer to call a taxi to take him home, before losing consciousness.

[12] Fricke himself was able to reconstruct the ensuing 24 hours only through the reports of others, but it seems that he was placed unconscious in a sleeping bag which was then concealed in a caravan and taken across the border into East Berlin.

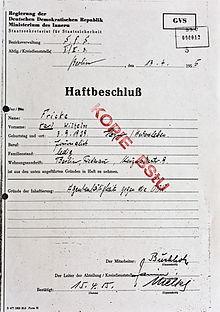

"[12] Having gone to the trouble of abducting and interrogating him, however, there was little logic in releasing Fricke, and in July 1956 he came before the Supreme Court in order to be condemned in a secret trial to fifteen years in prison for "Agitating for wars and boycotts".

[1] Looking back from more than half a century later, in 2013 Fricke opined that he had been fortunate not to have been kidnapped and interrogated by the Stasi a couple of years earlier than he was.

Although it was not always immediately apparent, the political temperature in the power hubs of East Berlin and Moscow did become less nervous as the 1950s progressed, and there was an accompanying diminution in the savagery with which the regime treated its identified enemies.

A Stasi internal paper from 1985 notes: The list of published articles and books from Karl Wilhelm Fricke is a long one.

[7] For many years he also chaired the advisory boards of the Berlin-Hohenschönhausen Memorial Museum and of the National Foundation for the Re-evaluation of the one-party GDR dictatorship.

[7] Today Fricke's books are standard works in the field of resistance and opposition, criminal justice and national security in the former German Democratic Republic (1949–1990).