Karlovy Vary

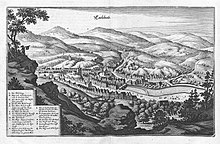

Karlovy Vary is named after Charles IV, Holy Roman Emperor and the King of Bohemia, who founded the city in the 14th century.

The site of numerous hot springs, the city grew into a spa resort in the 19th century and was a popular destination for the European aristocracy and other luminaries.

Karlovy Vary's rapid growth was brought to an end by the outbreak of World War I.

In 2021, the city became part of the transnational UNESCO World Heritage Site under the name "Great Spa Towns of Europe" because of its spas and architecture from the 18th through 20th centuries.

The historic city centre with the spa cultural landscape is well preserved and is protected by law as an urban monument reservation.

The northern part of the municipal territory with most of the built-up area lies in a relatively flat landscape of the Sokolov Basin.

People lived in close proximity to the site as far back as the 13th century and they must have been aware of the curative effects of thermal springs.

[9] According to legend, Charles IV organized an expedition into the forests surrounding modern-day Karlovy Vary during a stay in Loket.

Initiated by the Austrian Minister of State Klemens von Metternich, the decrees were intended to implement anti-liberal censorship within the German Confederation.

Due to publications produced by physicians such as David Becher and Josef von Löschner, the city developed into a spa resort in the 19th century and was visited by many members of European aristocracy as well as celebrities from many fields of endeavour.

The number of visitors rose from 134 families in the 1756 season to 26,000 guests annually at the end of the 19th century.

[14] At the end of World War I in 1918, the large German-speaking population of Bohemia was incorporated into the new state of Czechoslovakia in accordance with the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (1919).

[15] According to the 1930 census, the city was home to 23,901 inhabitants – 20,856 were ethnic Germans, 1,446 were Czechoslovaks (Czechs or Slovaks), 243 were Jews, 19 were Hungarians and 12 were Poles.

[16] In 1938, the city was annexed by Nazi Germany according to the terms of the Munich Agreement and administered as part of the Reichsgau Sudetenland.

[19] The city's economy is focused on services and only small and medium-sized industrial enterprises are based in it.

[23] The Karlovy Vary agglomeration was defined as a tool for drawing money from the European Structural and Investment Funds.

Although the infiltration area is several hundred square kilometres, each spring has the same hydrological origins, and therefore shares the same dissolved minerals and chemical formula.

[25] Local buses (Dopravní podnik Karlovy Vary) and cable cars take passengers to most areas of the city.

In the 19th century, Karlovy Vary became a popular tourist destination, especially known for international celebrities who visited for spa treatment.

Karlovy Vary is notable for its large concentration of monuments and architecturally valuable buildings.

[28] As part of the Great Spa Towns of Europe, Karlovy Vary became a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its spas and architecture from the 18th through 20th centuries.

It was built according to the design by Kilian Ignaz Dientzenhofer and belongs to the most important buildings of the Czech Baroque.

A cemetery was established next to the church for foreign guests of the spa who died in Karlovy Vary.

[38] The Church of Saint Leonard of Noblac was the oldest ecclesiastical structure in the territory of Karlovy Vary.