Kashmiri Pandits

The Hindu caste system of the Kashmir region was influenced by the influx of Buddhism from the time of Asoka, around the third century BCE, and a consequence of this was that the traditional lines of varna were blurred, with the exception of that for the Brahmins.

[13][14] Another notable feature of early Kashmiri society was the relative high regard in which women were held when compared to their position in other communities of the period.

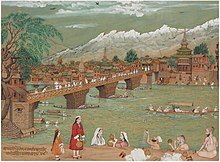

A historically contested region, Northern India was subject to attack from Turkic and Arab regimes from the eighth century onwards, but they generally ignored the mountain-circled Kashmir Valley in favour of easier pickings elsewhere.

[16][17] Mohibbul Hasan describes this collapse as The Dãmaras (feudal chiefs) grew powerful, defied royal authority, and by their constant revolts plunged the country into confusion.

[17]The Brahmins had something to be particularly unhappy about during the reign of the last Lohara king, for Sūhadeva chose to include them in his system of onerous taxation, whereas previously they appear to have been exempted.

[18] Zulju, who was probably a Mongol from Turkistan,[19] wreaked devastation in 1320, when he commanded a force that conquered many regions of the Kashmir Valley.

The Sultan has been referred to as an iconoclast because of his destruction of many non-Muslim religious symbols and the manner in which he forced the population to convert or flee.

[20][21] It was during the 14th century that the Kashmiri Pandits likely split into their three subcastes: Guru/Bāchabat (priests), Jotish (astrologers), and Kārkun (who were historically mainly employed by the government).

Sheth, the former director of the Center for the Study of Developing Societies in India (CSDS), lists Indian communities that constituted the middle class and were traditionally "Urban and professional" (following professions like doctors, lawyers, teachers, engineers, etc.)

This list included the Kashmiri Pandits, the Nagar Brahmins from Gujarat; the South Indian Brahmins; the Punjabi Khatris, and Kayasthas from northern India; Chitpawans and CKPs (Chandraseniya Kayastha Prabhus) from Maharashtra; the Probasi and the Bhadralok Bengalis; the Parsis and the upper crusts of Muslim and Christian communities.

On that day, mosques issued declarations that the Kashmiri Pandits were Kafirs and that the males had to leave Kashmir, convert to Islam or be killed.

The Kashmiri Muslims were instructed to identify Pandit homes so they could be systematically targeted for conversion or killing.

[38][39][40] In 2009 the Oregon Legislative Assembly passed a resolution to recognise 14 September 2007, as Martyrs Day to acknowledge ethnic cleansing and campaigns of terror inflicted on non-Muslim minorities of Jammu and Kashmir by terrorists seeking to establish an Islamic state.

[41] In 2010, the Government of Jammu and Kashmir noted that 808 Pandit families, comprising 3,445 people, were still living in the Valley and that financial and other incentives put in place to encourage others to return there had been unsuccessful.

These organisations are involved in rehabilitation of the community in the valley through peace negotiations, mobilisation of human rights groups and job creation for the Pandits.

[59] Scholar Christopher Snedden states that the Pandits made up about 6 per cent of the Kashmir Valley's population in 1947.

[56] Following the 1989 insurgency, a great majority of Pandits felt threatened and left the Kashmir Valley for other parts of India.

[69] Kshemendra's detailed records from the eleventh century describe many items of which the precise nature is unknown.

It is clear that tunics known as kanchuka were worn long-sleeved by men and in both long- and half-sleeved versions by women.

[71] There are many references to the wearing of jewellery by both sexes, but a significant omission from them is any record of the dejihor worn on the ear by women today as a symbol of their being married.

[75] The Kashmiri Pandits are divided into three subcastes: Guru/Bāchabat (priests), Jotish (astrologers), and Kārkun (who were historically mainly employed by the government).