Katharine Cornell

Dubbed "The First Lady of the Theatre" by critic Alexander Woollcott,[3] Cornell was the first performer to receive the Drama League Award, for Romeo and Juliet in 1935.

In 1919, she went with the Bonstelle company to London to play Jo March in Buffalo play-wright Marian de Forest's stage adaptation of Louisa May Alcott's novel Little Women.

Ashton Stevens, senior drama critic in Chicago, wrote that The Green Hat "should die at every performance of its melodramatics, its rouge and rhinestones, its preposterous third act....

According to biographer Tad Mosel, "she did not feel that she was acting for historians or nostalgia fans of the future but for audiences of the here and now, people who came into the theatre tonight, sat in their seats and waited for the curtain to go up.

"[citation needed]But other sources say that Hollywood secured Broadway plays for its own actors under contract and that Cornell was never considered for the roles she originated on stage.

[28] She declined many movie roles that earned Academy Awards wins and nominations for the actresses who did play those parts, such as Olan in The Good Earth and Pilar in For Whom the Bell Tolls.

Martha Graham, who choreographed the dance sequences, stepped in and fashioned a flowing robe for Juliet's balcony-scene costume shortly before curtain time.

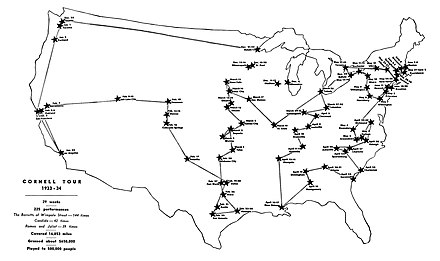

People in less urban areas traveled from two days away to see a performance, and the presenting towns gained a small but welcome swell in revenues from restaurants and hotels as a result.

They planned to arrive in the morning, and as it normally takes six hours to set up the stage, do lighting and blocking checks and distribute costumes, they figured there would be plenty of time.

For years afterward, every Christmas, Woollcott told the story of the Seattle audience that waited until 1 am to see Katharine Cornell "emerge from the flood" and give the performance of her life.

Taking note of the freshness of approach, Richard Lockridge of the New York Sun wrote that Cornell played Juliet as "an eager child, rushing toward love with arms stretched out."

John Mason Brown wrote in the New York Post: It is not often in our lifetime that we are privileged to enjoy the pleasant sensation of feeling that the present and the future have met for a few triumphant hours...Yet it was this very sensation—this uncommon sensation of having the present and future meet; eye-witnessing the kind of event to which we will be looking back with pride in the years to come—that forced its warming way, I suspect, into the consciousness of many of us last night as we sat spellbound.

It moves gracefully and lightly; it is endlessly haunting in its pictorial qualities; and reveals a Miss Cornell who equals the beauty of the lyric lines she speaks with a new-found lyric beauty of her own voice...To add that it is by all odds the most lovely and enchanting Juliet our present-day theatre has seen is only to toss it the kind of superlative it honestly deserves.Later, the same critic determined that this role was a turning point in Cornell's career, as it meant that she could finally leave the "trifling scripts" of her earlier career and could meet the challenging demands of the greatest classic roles.

[14][page needed] Romeo and Juliet closed on February 23, 1935, and two nights later, the production company revived The Barretts of Wimpole Street, with Burgess Meredith in his first prominent Broadway role.

McClintic cast Maurice Evans as the Dauphin, Brian Aherne as Warwick, Tyrone Power as Bertrand de Poulengey, and Arthur Byron as the Inquisitor.

Cornell's general manager Gertrude Macy produced a musical revue One for the Money, which starred unknown actors who later achieved fame, including Gene Kelly, Alfred Drake, Keenan Wynn and Nancy Hamilton.

Shortly after the U.S. entered World War II, Cornell decided upon a revival of Candida to benefit the Army Emergency Fund and the Navy Relief Society.

Cornell was able to convince all actors, Shaw, the theater hands and the Schubert organization to donate their labor, services and venue so that almost all proceeds went directly to the fund.

And when, next week, she brings her revival of Chekhov's 'The Three Sisters' to Broadway, it will boast a dream production by anybody's reckoning — the most glittering cast the theater has seen, commercially, in this generation.

[44] Cornell's only film role was speaking a few lines from Romeo and Juliet in the movie Stage Door Canteen (1943),[45] which starred many of Broadway's best actors, under the auspices of the American Theatre Wing for War Relief.

Kit and Guthrie were holding the laugh, just as if they had heard it a hundred times, not showing any alarm, not even seeming to wait for it, but handling it, controlling it, ready to take over at the first sign of its getting out of hand.

They thanked her for "the most nerve-soothing remedy for a weary G.I.," for having brought "yearned-for femininity," reminding them that, unlike other USO shows, "a woman is not all leg," and for "the awakening of something that I thought died with the passing of routine military life in the foreign service."

Long after the tour was finished, Cornell continued to receive letters, not just from servicemen who had seen the show, but from wives, mothers and even school teachers from the home front.

In her memoir, Cornell states: "I do think that the rapid success achieved by some people in pictures has seriously hurt the chances of a lot of young men and women who are studying for the stage.

"[12][page needed] Katharine Cornell is regarded as one of the most respected, versatile stage actresses of the early-mid 20th century, moving easily from comedy to melodrama, and from classics to contemporary plays.

A donation from her estate provided the funds for renovation (lighting, heating, elevator) as well as decoration of four large murals depicting Vineyard life and legend by local artist Stan Murphy.

[56] [57] The Katharine Cornell–Guthrie McClintic Special Collections Reading Room was dedicated in April 1974 at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts at Lincoln Center.

[60] The New York Public Library contains correspondence between Russian dance critic Igor Stupnikov and Cornell's assistants Nancy Hamilton and Gertrude Macy in the Billy Rose Theater Archive.

[80] The gallery also possesses a 1930 life mask by Karl Illava, an undated drawing of her as Elizabeth Barrett by Louis Lupas, and two sculptures by Anna Glenny Dunbar from 1930.

The foundation was dissolved in 1963, distributing its assets to the Museum of Modern Art (to honor her close friend from Buffalo, A. Conger Goodyear,[84] who was a founder of MoMA and its first president), Cornell University's theater department, and the Actor's Fund of America.