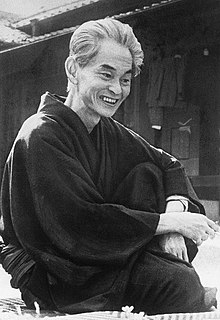

Yasunari Kawabata

In October 1924, Kawabata, Riichi Yokomitsu and other young writers started a new literary journal Bungei Jidai (The Artistic Age).

However, Shinkankakuha was not meant to be an updated or restored version of Impressionism; it focused on offering "new impressions" or, more accurately, "new sensations" or "new perceptions" in the writing of literature.

[5] An early example from this period is the draft of Hoshi wo nusunda chichi (The Father who stole a Star), an adaption of Ferenc Molnár's play Liliom.

The work explores the dawning eroticism of young love but includes shades of melancholy and even bitterness, which offset what might have otherwise been an overly sweet story.

In 1933, Kawabata protested publicly against the arrest, torture and death of the young leftist writer Takiji Kobayashi in Tokyo by the Tokkō special political police.

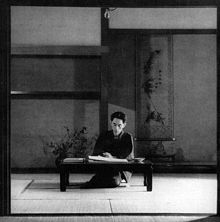

Snow Country is a stark tale of a love affair between a Tokyo dilettante and a provincial geisha, which takes place in a remote hot-spring town somewhere in the mountainous regions of northern Japan.

The tea ceremony provides a beautiful background for ugly human affairs, but Kawabata's intent is rather to explore feelings about death.

These themes of impossible love and impending death are again explored in The Sound of the Mountain (serialized 1949-1954), set in Kawabata's adopted home of Kamakura.

It was the last game of master Shūsai's career and he lost to his younger challenger, Minoru Kitani, only to die a little over a year later.

Although the novel is moving on the surface as a retelling of a climactic struggle, some readers consider it a symbolic parallel to the defeat of Japan in World War II.

In a 1934 published work Kawabata wrote: "I feel as though I have never held a woman's hand in a romantic sense [...] Am I a happy man deserving of pity?”.

[citation needed] Indeed, this does not have to be taken literally, but it does show the type of emotional insecurity that Kawabata felt, especially experiencing two painful love affairs at a young age.

Although he refused to participate in the militaristic fervor that accompanied World War II, he also demonstrated little interest in postwar political reforms.

Along with the death of all his family members while he was young, Kawabata suggested that the war was one of the greatest influences on his work, stating he would be able to write only elegies in postwar Japan.

[12] In awarding the prize "for his narrative mastery, which with great sensibility expresses the essence of the Japanese mind", the Nobel Committee cited three of his novels, Snow Country, Thousand Cranes, and The Old Capital.

From painting he moved on to talk about ikebana and bonsai as art forms that emphasize the elegance and beauty that arises from the simplicity.

[citation needed] Kawabata apparently committed suicide in 1972 by gassing himself, but several close associates and friends, including his widow, consider his death to have been accidental.

Many theories have been advanced as to his potential reasons for killing himself, among them poor health (the discovery he had Parkinson's disease), a possible illicit love affair, or the shock caused by the suicide of his friend Yukio Mishima in 1970.