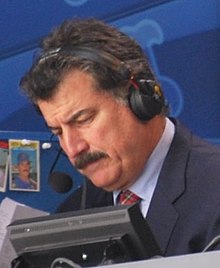

Keith Hernandez

Hernandez was a five-time All-Star who shared the 1979 NL MVP award and won two World Series titles, one each with the Cardinals and Mets.

Hernandez was perceived as having attitude issues because he sat out his entire senior high school season due to a dispute with a coach.

His interest in the Civil War landed Hernandez guest spots on KMOX radio when he was with the Cardinals, was featured in the New York Times when he was with the Mets, and appeared in episodes of the television series Seinfeld.

Hernandez's batting average hovered around .250 for most of his minor league career, until his promotion to the Tulsa Oilers in the second half of the 1973 season.

[8] Following the season, the Cards traded first baseman Joe Torre to the New York Mets for Tommy Moore and Ray Sadecki to make room for their budding young prospect.

Though he had a .996 fielding percentage with only two errors in 507 chances, Hernandez struggled with major league pitching, batting only .250 with three home runs and 20 RBIs.

While Hernandez became more comfortable with his bat, he was always recognized as a fielder first, snatching his first Gold Glove Award away from perennial winner Steve Garvey in 1978.

For the first and only time in major league history, two players received the same number of points from the Baseball Writers' Association of America and shared the MVP award for that year.

As a result of this trade, Hernandez went from a World Series champion to a team that narrowly avoided a hundred losses (68–94) and consistently finished at the bottom of the National League East.

Hernandez finished second in the NL Most Valuable Player voting behind Cubs second baseman Ryne Sandberg, and emerged as the leader of the Mets' young core of ballplayers that included 1983 and 1984 Rookies of the Year Darryl Strawberry and Dwight Gooden, respectively.

Pete Rose, when he managed the Cincinnati Reds, compared bunting against Hernandez to "driving the lane against Bill Russell."

Hernandez also was adept at picking runners off first base by taking pickoff throws with his right foot on the bag and his left in foul territory so that he could make tags to his right more readily.

In 1985, Hernandez's previous cocaine use (and distribution of the drug to other players),[11] which had been the subject of persistent rumors and the chief source of friction between Hernandez and Cardinals manager Whitey Herzog,[12] became a matter of public record as a result of the Pittsburgh trial of drug dealer Curtis Strong.

The players received season-long suspensions, that were commuted on condition that they donated ten percent of their base salaries to drug-abuse programs, submitted to random drug testing, and contributed 100 hours of drug-related community service.

Initially, Hernandez considered challenging Ueberroth's finding against him, but ultimately accepted the option available, which allowed him to avoid missing any playing time.

Well before the commissioner's decision, the Mets and Cardinals had become embroiled in a heated rivalry atop the National League East, with Hernandez, newly acquired All-star catcher Gary Carter, and other talented veterans combining with a spectacular group of young talent to lead the charge for the Mets.

The Mets had three players finish in the top ten in NL MVP balloting that season (Gooden 4th, Carter 6th, and Hernandez 8th).

Meanwhile, the "Redbirds" placed four players in the top ten: winner Willie McGee), (Tommy Herr 5th, John Tudor tied Hernandez at 8th, Jack Clark 10th, and had the 11th-place finisher (Vince Coleman).

Hernandez credits his father, who played ball with Stan Musial when they were both in the Navy during World War II, for helping him out of a batting slump in 1985.

[citation needed] His father would observe his at-bats on TV and note that when Keith was hitting well, he could see both the "1" and the "7" on his uniform on his back as he began to stride into the pitch.

In Game 7, Hernandez broke through against Red Sox lefty Bruce Hurst, who had shut out the Mets into the sixth inning, with a clutch two-run single.

Given his drug suspension deal and the team’s "party hard; play harder" culture, Hernandez became seen by some as the poster-boy for the Mets of the '80s.

In 1988 he was featured heavily in the William Goldman and Mike Lupica book "Wait Till Next Year", which looked at life inside the Mets over the whole 1987 season (among other New York sports teams).

Hernandez is portrayed as the most vocal of the Mets in dealing with the press and giving his opinion on teammates, alongside his prodigious beer consumption.

[16] The book covers his life through early in the 1980 season, and, depending on sales, may lead to a follow-up tome picking up the narrative from that point.

He also won 11 Gold Glove awards for his glovework at first base, setting a Major League record for the position that still stands.

In the episode, Hernandez dates Julia Louis-Dreyfus's character Elaine Benes, and Jerry Seinfeld develops the male-bonding equivalent of a crush on him.

One sports fan, who refuses to respect the day by wearing a mustache, is met by the steely, disapproving stare of Hernandez himself.

[32] Hernandez has donated thousands of dollars to GOP candidates, including Donald Trump, Mitch McConnell, Marco Rubio, Susan Collins, Rudy Giuliani, Allen West, David Perdue, and Kelly Loeffler.

[33] On November 19, 2021, Hernandez tweeted a photograph of Robert F. Kennedy Jr.'s anti-vaccine book The Real Anthony Fauci: Bill Gates, Big Pharma, and the Global War on Democracy and Public Health with the caption "Just released."