Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

The Virginia Resolutions of 1798 refer to "interposition" to express the idea that the states have a right to "interpose" to prevent harm caused by unconstitutional laws.

[1] George Washington was so appalled by them that he told Patrick Henry that if "systematically and pertinaciously pursued", they would "dissolve the union or produce coercion".

[2] In the years leading up to the Nullification Crisis, the resolutions divided Jeffersonian democrats, with states' rights proponents such as John C. Calhoun supporting the Principles of '98 and President Andrew Jackson opposing them.

Years later, the passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 led anti-slavery activists to quote the Resolutions to support their calls on Northern states to nullify what they considered unconstitutional enforcement of the law.

Rather, the 1799 Resolutions declared that Kentucky "will bow to the laws of the Union" but would continue "to oppose in a constitutional manner" the Alien and Sedition Acts.

Numerous scholars (including Koch and Ammon) have noted that Madison had the words "void, and of no force or effect" excised from the Virginia Resolutions before adoption.

Taylor rejoiced in what the House of Delegates had made of Madison's draft: it had read the claim that the Alien and Sedition Acts were unconstitutional as meaning that they had "no force or effect" in Virginia—that is, that they were void.

Future Virginia Governor and U.S. Secretary of War James Barbour concluded that "unconstitutional" included "void, and of no force or effect", and that Madison's textual change did not affect the meaning.

[10] The long-term importance of the Resolutions lies not in their attack on the Alien and Sedition Acts, but rather in their strong statements of states' rights theory, which led to the rather different concepts of nullification and interposition.

"We think it highly probable that Virginia and Kentucky will be sadly disappointed in their infernal plan of exciting insurrections and tumults," proclaimed one.

[16] At the Virginia General Assembly, delegate John Mathews was said to have objected to the passing of the resolutions by "tearing them into pieces and trampling them underfoot.

However, in the same document Madison explicitly argued that the states retain the ultimate power to decide about the constitutionality of the federal laws, in "extreme cases" such as the Alien and Sedition Act.

The Supreme Court can decide in the last resort only in those cases which pertain to the acts of other branches of the federal government, but cannot takeover the ultimate decision-making power from the states which are the "sovereign parties" in the Constitutional compact.

Several years later, Massachusetts and Connecticut asserted their right to test constitutionality when instructed to send their militias to defend the coast during the War of 1812.

We spurn the idea that the free, sovereign and independent State of Massachusetts is reduced to a mere municipal corporation, without power to protect its people, and to defend them from oppression, from whatever quarter it comes.

Whenever the national compact is violated, and the citizens of this State are oppressed by cruel and unauthorized laws, this Legislature is bound to interpose its power, and wrest from the oppressor its victim.

"[20] Madison went on to argue that the purpose of the Virginia Resolution had been to elicit cooperation by the other states in seeking change through means provided in the Constitution, such as an amendment.

The Supreme Court rejected the compact theory in several nineteenth century cases, undermining the basis for the Kentucky and Virginia resolutions.

In cases such as Martin v. Hunter's Lessee,[23] McCulloch v. Maryland,[24] and Texas v. White,[25] the Court asserted that the Constitution was established directly by the people, rather than being a compact among the states.

James J. Kilpatrick, an editor of the Richmond News Leader, wrote a series of editorials urging "massive resistance" to integration of the schools.

Kilpatrick, relying on the Virginia Resolution, revived the idea of interposition by the states as a constitutional basis for resisting federal government action.

[26] A number of southern states, including Arkansas, Louisiana, Virginia, and Florida, subsequently passed interposition and nullification laws in an effort to prevent integration of their schools.

But since the defense involved an appeal to principles of state rights, the resolutions struck a line of argument potentially as dangerous to the Union as were the odious laws to the freedom with which it was identified.

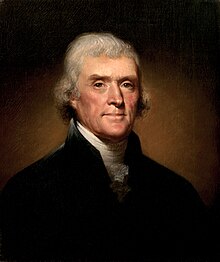

[31] In writing the Kentucky Resolutions, Jefferson warned that, "unless arrested at the threshold", the Alien and Sedition Acts would "necessarily drive these states into revolution and blood."

[1] Historian Garry Wills argued "Their nullification effort, if others had picked it up, would have been a greater threat to freedom than the misguided [alien and sedition] laws, which were soon rendered feckless by ridicule and electoral pressure".

[1] George Washington was so appalled by them that he told Patrick Henry that if "systematically and pertinaciously pursued", they would "dissolve the union or produce coercion".

[2] Future president James Garfield, at the close of the Civil War, said that Jefferson's Kentucky Resolution "contained the germ of nullification and secession, and we are today reaping the fruits".