Kepler conjecture

In 1998, Thomas Hales, following an approach suggested by Fejes Tóth (1953), announced that he had a proof of the Kepler conjecture.

[1] Imagine filling a large container with small equal-sized spheres: Say a porcelain gallon jug with identical marbles.

Experiment shows that dropping the marbles in randomly, with no effort to arrange them tightly, will achieve a density of around 65%.

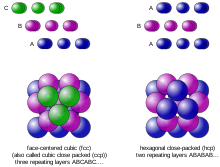

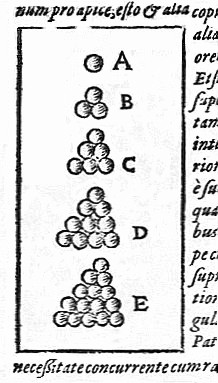

[2] However, a higher density can be achieved by carefully arranging the marbles as follows: At each step there are at least two choices of how to place the next layer, so this otherwise unplanned method of stacking the spheres creates an uncountably infinite number of equally dense packings.

He had started to study arrangements of spheres as a result of his correspondence with the English mathematician and astronomer Thomas Harriot in 1606.

But eliminating all possible irregular arrangements is very difficult, and this is what made the Kepler conjecture so hard to prove.

Fejes Tóth (1953) showed that the problem of determining the maximum density of all arrangements (regular and irregular) could be reduced to a finite (but very large) number of calculations.

As Fejes Tóth realised, a fast enough computer could turn this theoretical result into a practical approach to the problem.

[5] Following the approach suggested[6] by László Fejes Tóth, Thomas Hales, then at the University of Michigan, determined that the maximum density of all arrangements could be found by minimizing a function with 150 variables.

Despite the unusual nature of the proof, the editors of the Annals of Mathematics agreed to publish it, provided it was accepted by a panel of twelve referees.

In January 2003, Hales announced the start of a collaborative project to produce a complete formal proof of the Kepler conjecture.