Carnac stones

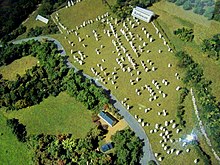

More than 3,000 prehistoric standing stones were hewn from local granite and erected by the pre-Celtic people of Brittany and form the largest such collection in the world.

[2] Although the stones date from 4500–3300 BC, modern beliefs associated them with 1st century AD Roman and later Christian occupations.

Local tradition similarly claims that the reason they stand in such perfectly straight lines is that they are a Roman legion turned to stone by Merlin.

In recent centuries, many of the sites have been neglected, with reports of dolmens being used as sheep shelters, chicken sheds or even ovens.

[1][7] According to Neil Oliver's BBC documentary A History of Ancient Britain,[8] the alignments would have been built by hunter-gatherer people ("These weren't erected by Neolithic farmers, but by Mesolithic hunters").

The standing stones are made of weathered granite from local outcroppings that once extensively covered the area.

[citation needed] A much smaller group, further east again of Kerlescan, falling within the commune of La Trinité-sur-Mer.

In this area, they generally feature a passage leading to a central chamber which once held neolithic artifacts.

Three exceptionally large burial mounds are known from the Carnac and Morbihan area, dating from the mid-5th millennium BC and known collectively as 'Carnacéen tumuli': Saint-Michel, Tumiac and Mané-er-Hroëk.

[18] Scientific analyses have shown that many of the axeheads are made of jade from the Italian Alps, whilst the callaïs was imported from south-western Iberia.

[19] Some of the Carnacéen jade axeheads are up to 46 cm in length and may have taken over a thousand hours to produce, on top of the time required to quarry the material and transport it to Carnac.

[22][23][24] The large-scale effort and organisation involved in the construction of megalithic monuments, such as the 20.6 metre-tall Grand Menhir of Er Grah, further suggests the existence of rulers or kings in the Carnac and Morbihan region.

[29] Similarities have also been noted with the Michelsberg culture in northeastern France and Germany (c. 4200 BC), which featured large tumulus burials within fortified settlements and the use of Alpine jade axes, all associated with the emergence of "high-ranking elites".

[30][31] Engravings on megalithic monuments in Carnac also feature numerous depictions of objects interpreted as symbols of authority and power, such as curved throwing weapons, axes and sceptres.

It contained various funerary objects, such as 15 stone chests, large jade axes, pottery, and callaïs jewellery, most of which are currently held by the Museum of Prehistory of Carnac.

The tumulus comprises a rectangular burial vault of about 5 m by 3 m, covered with two roofing slabs, supporting a mound about 100 m long and 60 m wide.

In many cases, the mound is no longer present, sometimes due to archeological excavation, and only the large stones remain, in various states of ruin.

Previously surrounded by a circle of small menhirs 4 m (13 ft) out,[39] the main passage is 6.5 m (21 ft) long and leads to a large chamber where numerous artifacts were found, including axes, arrowheads, some animal and human teeth, some pearls and sherds, and 26 beads of a unique bluish Nephrite gem.

(Pixies' mound or Grotte de Grionnec[39]):A group of three dolmens with layout unique in Brittany,[39] once covered by a tumulus.

[48] Ronalds created the first accurate drawings of many of them with his patented perspective tracing instrument, which were printed in a book Sketches at Carnac (Brittany) in 1834.

[49] The first extensive excavation was performed in the 1860s by Scottish antiquary James Miln (1819–1881), who reported that by then fewer than 700 of the 3,000 stones were still standing.

[15] The Musée de Préhistoire James Miln – Zacharie le Rouzic is at the centre of conserving and displaying the artefacts from the area.

This involved restricting public access, launching a series of scientific and technical studies, and producing a plan for conservation and development in the area.

Since 1991, the main groups of stone rows have been protected from the public by fences "to help vegetation growth",[38] preventing visits except by organised tours.

[58] In recent years, management of the site has also experimented with allowing sheep to graze among the stones, in order to keep gorse and other weeds under control.

[59] In June 2023, 39 menhirs still outside the UNESCO protected site were destroyed to construct a DIY store of the Mr. Bricolage franchise, which obtained a building permit from the local town hall in August 2022.

The town's mayor, Olivier Lepick, told AFP that he had "followed the law" and pointed to the "low archaeological value" of objects found during checks before the construction process began.

While Lepick blamed the region's complex zoning situation, the researcher Christian Obeltz claimed that "elected officials in the area and the department are in a hurry to build up anything because once it is classified with UNESCO, it won't be possible anymore".

The local Koun Breizh association has decided to lodge a complaint with the public prosecutor of Vannes for willful destruction of sites that relate to archaeological heritage.