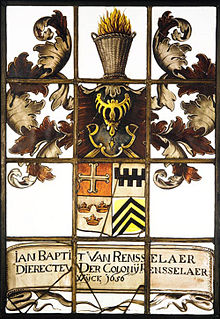

Kiliaen van Rensselaer (merchant)

The concept of patroonships may have been Kiliaen van Rensselaer's; he was likely the leading proponent of the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions, the document that established the patroon system.

His patroonship became the most successful to exist, making full use of his business tactics and advantages, such as his connection to the Director of New Netherland, his confidantes at the West India Company, and his extended family members who were eager to immigrate to a better place to farm.

The American Van Rensselaers all descend from Kiliaen's son Jeremias and the subsequent Van Rensselaer family is noted for being a very powerful and wealthy influence in the history of New York and the Northeastern United States, producing multiple State Legislators, Congressmen, and two Lieutenant Governors in New York.

[8][11] Some of Van Rensselaer's success as a jewel merchant came about due to trade made possible by the Dutch East India Company.

During the Twelve Years' Truce, Dutch merchants had sailed unmolested to the West Indies but also received no letters of marque to take prizes from the enemy.

[13] Before the Eighty Years' War began, people realized that the West Indies trade might bring great prosperity to the country and that more power might be developed against Spain.

[13] After long years of preparation, the Charter of the Dutch West India Company was granted by the States General on 3 June 1621, and the subscription list was opened.

[13] With a capital of seven million florins, the West India Company was granted exclusive authority and trade privileges in the Dutch possessions of the two Americas, as well as the coast of Africa from the Tropic of Cancer to the Cape of Good Hope.

The objects of its creation were to establish an efficient and aggressive Atlantic maritime power in the struggle with Spain, as well as to colonize, develop, and rule the Dutch American dependencies — particularly New Netherland (the modern states of New York and New Jersey), discovered by Henry Hudson in 1609.

[18] The Chamber of Amsterdam was the largest with twenty members,[19] mainly due to the city's population, and represented four ninths of the management of the West India Company.

[18] Van Rensselaer was apparently known as an unusually clear-headed man and an able and practical merchant who did not limit himself to his own branch of trade.

[22] In its role supporting colonization of New Netherland, the West India Company had an executive board of nine members from the College of XIX to manage the concerns of their colony.

This document was created to encourage settlement of New Netherland through the establishment of feudal patroonships purchased and supplied by members of the West India Company.

[27] In return, the patroons were able to own the land and pass it to succeeding generations as a perpetual fiefdom,[28] as well as receive protection[29] and free African slaves from the Company.

The Company was not inclined to involve itself in further expense for colonization, and matters threatened to come to a halt, when someone — very likely Van Rensselaer himself — evolved the plan of granting large estates to men willing to pay the cost of settling and operating them.

[33] Van Rensselaer was quick to take part in the new endeavor: on 13 January 1629, he sent notification[34] to the Directors of the Company that he, in conjunction with fellow Company members Samuel Godin and Samuel Blommaert, had sent Gillis Houset and Jacob Jansz Cuyper to determine satisfactory locations for settlement.

The location relative to the fort was chosen with care — in case of danger, it would be a sure point of defense or retreat, and its garrison would be very likely to intimidate the natives.

[38] His first act was to obtain possession of the land for his colony from the Mohican, the original owners, who had never been willing to sell their territory — not even the ground of Fort Orange.

As an owner of extensive lands in the sandy Gooi[f] and of family estates in the not much more fruitful Veluwe, where several relatives were landowners and struggled to subsist on meager means, Van Rensselaer had an advantage — his agents needed to employ little persuasion to induce some Gooiers and Veluwers to migrate to more fruitful regions where the farming would be less difficult.

Three of them would have a one-fifth share in each colony, while the fourth would receive the remaining two fifths, taking the responsibility for its management and exercising patroon rights.

[11] The same year, the young husband purchased a couple of lots on the east side of the recently dug Keizersgracht in Amsterdam, between Marten and Wolven streets, where he built a house.

[13] Hillegonda van Bijler is presumed to have died in late December 1626, since she was buried on 1 January 1627, three days before her third child Maria.

[58] Notably, at the time of his death, Stephen III was worth about $10 million (about $88 billion in 2007 dollars) and is noted as being the tenth-richest American in history.

[61] The family records, many of which were translated and published in the Van Rensselaer Bowier Manuscripts, reveal the personality of the man who figures prominently in the history of colonization as the founder of the only successful patroonship that ever existed in New Netherland.

But beyond the fact that he managed this patroonship and that he was a merchant and director of the West India Company, practically nothing was known until the organization and translation of the family records in the early 1900s (decade).

![A short, wide parchment map shows the "Noord Rivier" (North River) traveling from right to left along the center of the parchment, in addition to the proposed locations of small settlements. Another river is also shown, at the very right, traveling from the top of the parchment to its connection at the Noord. The map is entitled "RENSELAERSWYCK" [sic] in large letters and the contains two shields and two scrolls containing Dutch text.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/f/fa/Rensselaerswyck_Original_Map_Small.png/400px-Rensselaerswyck_Original_Map_Small.png)