Kindertransport

[4][5][6] The term "Kindertransport" may also be applied to the rescue of mainly Jewish children from Nazi German territory to the Netherlands, Belgium, and France.

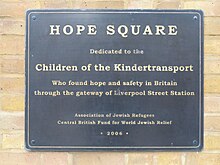

[8] The Central British Fund for German Jewry (now World Jewish Relief) was established in 1933 to support in whatever way possible the needs of Jews in Germany and Austria.

In the United States, the Wagner–Rogers Bill was introduced in Congress, which would have increased the quota of immigrants by bringing to the U.S. a total of 20,000 refugee children, but it did not pass.

On 15 November 1938, five days after the devastation of Kristallnacht, the "Night of Broken Glass", in Germany and Austria, a delegation of British, Jewish, and Quaker leaders appealed, in person, to the Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, Neville Chamberlain.

[10] The bill stated that the government would waive certain immigration requirements so as to allow the entry into Great Britain of unaccompanied children ranging from infants up to the age of 17, under a number of conditions.

However, after the British Colonial Office turned down the Jewish agencies' separate request to allow the admission of 10,000 children to British-controlled Mandatory Palestine, "this number seems to have been adopted informally as an appropriate goal for Britain herself to meet.

Eventually around 500 Jewish children from Germany aged between 1 and 15 were granted temporary residence permits on the condition that their parents would not try to enter the country.

Depending on the child's age, the explanation for why they were leaving the country and their parents differed widely: for example, children might be told "you are going on an exciting adventure", or "you are going on a short trip and we will see you soon".

[citation needed] Older refugee children became fully aware of the war in Europe during the period of 1939–1945 and would become concerned for their parents.

She persevered however, until finally, as she wrote in her biography, Eichmann suddenly "gave" her 600 children with the clear intent of overloading her and making a transport on such short notice impossible.

Nevertheless, Wijsmuller-Meijer managed to send 500 of the children to Harwich, where they were accommodated in a nearby holiday camp at Dovercourt, while the remaining 100 found refuge in the Netherlands.

[45] Marking the European route of the children's transport and created from personal experience,[46] Frank Meisler's sculpture groups show similarities but with different details.

Depicted in different colours, the group of the rescued is outnumbered, as the majority of Jewish children (more than one million) perished in the Nazi death camps.

In September 2022 a bronze memorial entitled Safe Haven was unveiled on Harwich Quay by Dame Steve Shirley, a former Kindertransport child.

[48] The work by artist Ian Wolter is a life-size, bronze sculpture of five Kindertransport refugees descending a ship's gangplank.

A number of members of Habonim, a Jewish youth movement inclined to socialism and Zionism, were instrumental in running the country hostels of South West England.

[50] Before Christmas 1938, Nicholas Winton, a 29-year-old British stockbroker of German-Jewish origin, travelled to Prague to help a friend involved in Jewish refugee work.

[52][53] Winton's mother also worked with him to place the children in homes, and later hostels, with a team of sponsors from groups like Maidenhead Rotary Club and Rugby Refugee Committee.

The last group of children, which left Prague on 3 September 1939, was turned back because the Nazis had invaded Poland – the beginning of the Second World War.

He was well liked by the UK government and in Parliament and convinced many parliamentarians to pass a Motion allowing Jewish refugees from the Nazis to find safety in places within the British Empire.

[citation needed] As the camp internees reached the age of 18, they were offered the chance to do war work or to enter the Army Auxiliary Pioneer Corps.

Several dozen joined elite formations such as the Special Forces, where their language skills were put to good use during the Normandy landings, and afterwards as the Allies progressed into Germany.

However, due to opposition from Senator Robert Rice Reynolds, it never left the committee stage and failed to get Congressional approval.

[64] A number of children saved by the Kindertransports went on to become prominent figures in public life, with two (Walter Kohn, Arno Penzias) becoming Nobel Prize winners.

[72] The Kindertransport Association is a national American not-for-profit organisation whose goal is to unite these child Holocaust refugees and their descendants.

The association shares their stories, honours those who made the Kindertransport possible, and supports charitable work that aids children in need.

In the United Kingdom, the Association of Jewish Refugees houses a special interest group called the Kindertransport Organisation.

[80] Jessica Reinisch notes how the British media and politicians alike allude to the Kindertransport in contemporary debates on refugee and migration crises.

She argues that "the Kindertransport" is used as evidence of Britain's "proud tradition" of taking in refugees; but that such allusions are problematic as the Kinderstransport model is taken out of context and thus subject to nostalgia.

She points out that countries such as Britain and the United States did much to prevent immigration by turning desperate people away; at the Évian Conference in 1938, participant nations failed to reach agreement about accepting Jewish refugees who were fleeing Nazi Germany.

Vienna, Westbahnhof Station 2008, a tribute to the British people for saving the lives of thousands of children from Nazi terror through the Kindertransports