King Island emu

Its closest relative may be the also extinct Tasmanian emu (D. n. diemenensis), as they belonged to a single population until less than 14,000 years ago, when Tasmania and King Island were still connected.

The subspecies was distinct from the likewise small and extinct Kangaroo Island emu (D. n. baudinianus) in a number of osteological details, including size.

The two live King Island specimens were kept in the Jardin des Plantes, and the remains of these and the other birds are scattered throughout various museums in Europe today.

The logbooks of the expedition did not specify from which island each captured bird originated, or even that they were taxonomically distinct, so their status remained unclear until more than a century later.

The logbooks of the expedition failed to clearly state where and when the small emu individuals were collected, and this has resulted in a plethora of scientific names subsequently being coined for either bird, many on questionable grounds, and the idea that all specimens had originated from Kangaroo Island.

[5] Various collectors found subfossil emu remains on King Island during the early 20th century, the first by the Australian amateur ornithologist Archibald James Campbell in 1903, near a lagoon on the east coast.

[9] In his 1907 book Extinct Birds, the British zoologist Walter Rothschild stated that Vieillot's description actually referred to the mainland emu, and that the name D. ater was therefore invalid.

Believing the skin in Muséum national d'Histoire naturelle of Paris was from Kangaroo Island, he made it the type specimen of his new species Dromaius peroni, named after the French naturalist François Péron, who is the main source of information about the bird in life.

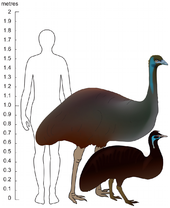

[17] There are few morphological differences that distinguish the extinct insular emus from the mainland emu besides their size, but all three taxa were most often considered distinct species.

A 2011 study by the Australian geneticist Tim H. Heupink and colleagues of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA, which was extracted from five subfossil King Island emu bones, showed that its genetic variation fell within that of the extant mainland emus.

[20] In 2014–2015, the English palaeontologist Julian Hume and colleagues conducted a search for emu fossils on King Island; no major palaeontological surveys had been done since the early 20th century, apart from discoveries made by the local natural historian Christian Robertson during the preceding thirty years.

[21][22] During the Late Quaternary period (0.7 million years ago), small emus lived on a number of offshore islands of mainland Australia.

As a result of phenotypic plasticity the King Island emu population possibly underwent a process of insular dwarfism.

[18] Emu eggshells were also identified from Flinders Island (in the opposite, eastern end of the Bass Strait) in 2017, possibly representing a distinct taxon.

[18] Models of sea level change indicate that Tasmania, including King Island, was isolated from the Australian mainland around 14,000 years ago.

[18] A 2018 study by Australian geneticist Vicki A. Thomson and colleagues (based on ancient bone, eggshell and feather samples) found that the emus of Kangaroo Island and Tasmania also represented sub-populations of the mainland emu, and therefore belonged in the same species.

This suggest that island size was the important driver in dwarfism of these emus, probably due to limitation in resources, though the exact effect needs to be confirmed.

According to Péron's interview with the local English sealer Daniel Cooper, the largest specimens were up to 137 cm (4.5 ft) in length, and the heaviest weighed 20 to 23 kg (45 to 50 lb).

[13] Since the female mainland emus are on average larger than the males, and can turn brighter during the mating season, contrary to the norm in other bird species, the Australian museum curator Stephanie Pfennigwerth suggested that some of these observations may have been based on erroneous conventional wisdom.

[12] Additional traits that supposedly distinguish this bird from the mainland emu have previously been suggested to be the distal foramen of the tarsometatarsus, and the contour of the cranium.

[13][27] The English Captain Matthew Flinders did not encounter emus when he visited King Island in 1802, but his naturalist, Robert Brown, examined their dung and noted they had chiefly fed on the berries of Leptecophylla juniperina.

[4] An account by English ornithologist John Latham about the "Van Diemen's cassowary" may also refer to the King Island emu, based on the small size described.

Hume and Robertson attempted to explain these findings, and noted that emus and other ratites have precocial juveniles, that is, relatively mature and mobile when they hatch, and appear to have laid their eggs at the same time.

[21][22] Hume and Robertson suggested the evolutionary advantage for the small emus in retaining large eggs and precocial chicks was driven mainly by limited food resources on their islands.

Their chicks had to be large enough to feed on seasonably available food, and possibly to develop thermoregulation sufficient for them to deal with cool temperatures, as is the case for mainland emus and kiwis.

In accordance with a request by the authorities for the expedition to bring back useful plants and animals, Péron asked if the emus could be bred and fattened in captivity, and received a variety of cooking recipes.

[4] There is also a skeleton in the Royal Zoological Museum, Florence, which it obtained from France in 1833, but was mislabelled as a cassowary and used by students until correctly identified by Italian zoologist Enrico Hillyer Giglioli in 1900.

Lesueur's preparatory sketches also indicate these may have been drawn after the captive birds in Jardin des Plantes, and not wild ones, which would have been harder to observe for extended periods.

A crooked claw on the "male" has also been interpreted as evidence that it had lived in captivity, and it may also indicate that the depicted specimen is identical to the Kangaroo Island emu skeleton in Paris, which has a deformed toe.

The juvenile on the right may have been based on the Paris skin of an approximately five-month-old emu specimen (from either King or Kangaroo Island), which may in turn be the individual that died on board le Geographe during rough weather, and was presumably stuffed there by Lesueur himself.