Offa of Mercia

Taking advantage of instability in the kingdom of Kent to establish himself as overlord, Offa also controlled Sussex by 771, though his authority did not remain unchallenged in either territory.

In the 780s he extended Mercian Supremacy over most of southern England, allying with Beorhtric of Wessex, who married Offa's daughter Eadburh, and regained complete control of the southeast.

This reduction in the power of Canterbury may have been motivated by Offa's desire to have an archbishop consecrate his son Ecgfrith as king, since it is possible Jænberht refused to perform the ceremony, which took place in 787.

The Chronicle was a West Saxon production, however, and is sometimes thought to be biased in favour of Wessex; hence it may not accurately convey the extent of power achieved by Offa, a Mercian.

[11] Other surviving sources include a problematic document known as the Tribal Hidage, which may provide further evidence of Offa's scope as a ruler, though its attribution to his reign is disputed.

[12] A significant corpus of letters dates from the period, especially from Alcuin, an English deacon and scholar who spent over a decade at Charlemagne's court as one of his chief advisors, and corresponded with kings, nobles and ecclesiastics throughout England.

Charters dating from the first two years of Offa's reign show the Hwiccan kings as reguli, or kinglets, under his authority; and it is likely that he was also quick to gain control over the Magonsæte, for whom there is no record of an independent ruler after 740.

[1][22] Little is known about the history of the East Saxons during the 8th century, but what evidence there is indicates that both London and Middlesex, which had been part of the kingdom of Essex, were finally brought under Mercian control during the reign of Æthelbald.

The overlordship of the southern English which had been exerted by Æthelbald appears to have collapsed during the civil strife over the succession, and it is not until 764, when evidence emerges of Offa's influence in Kent, that Mercian power can be seen expanding again.

[38] However, doubts have been expressed about the authenticity of the charters which support this version of events, and it is possible that Offa's direct involvement in Sussex was limited to a short period around 770–71.

[42] The legend also claims that Æthelberht was killed at Sutton St. Michael and buried four miles (6 km) to the south at Hereford, where his cult flourished, becoming at one time second only to Canterbury as a pilgrimage destination.

[57] There are settlements to the west of the dyke that have names that imply they were English by the 8th century, so it may be that in choosing the location of the barrier the Mercians were consciously surrendering some territory to the native Britons.

[61] Offa ruled as a Christian king, but despite being praised by Charlemagne's advisor, Alcuin, for his piety and efforts to "instruct [his people] in the precepts of God",[62] he came into conflict with Jænberht, the Archbishop of Canterbury.

[63] In 786 Pope Adrian I sent papal legates to England to assess the state of the church and provide canons (ecclesiastical decrees) for the guidance of the English kings, nobles and clergy.

Two versions of the events appear in the form of an exchange of letters between Coenwulf, who became king of Mercia shortly after Offa's death, and Pope Leo III, in 798.

Coenwulf asserts in his letter that Offa wanted the new archdiocese created out of enmity for Jænberht; but Leo responds that the only reason the papacy agreed to the creation was because of the size of the kingdom of Mercia.

[69] Coenwulf's version has independent support, with a letter from Alcuin to Archbishop Æthelheard giving his opinion that Canterbury's archdiocese had been divided "not, as it seems, by reasonable consideration, but by a certain desire for power".

Offa would have been aware that Charlemagne's sons, Pippin and Louis, had been consecrated as kings by Pope Adrian,[74] and probably wished to emulate the impressive dignity of the Frankish court.

[81] Control of religious houses was one way in which a ruler of the day could provide for his family, and to this end Offa ensured (by acquiring papal privileges) that many of them would remain the property of his wife or children after his death.

[80] This policy of treating religious houses as worldly possessions represents a change from the early 8th century, when many charters showed the foundation and endowment of small minsters, rather than the assignment of those lands to laypeople.

It is clear that Charlemagne's policy included support for elements opposed to Offa; in addition to sheltering Egbert and Eadberht he also sent gifts to Æthelred I of Northumbria.

By 796 Charlemagne had become master of an empire which stretched from the Atlantic Ocean to the Great Hungarian Plain, and Offa and then Coenwulf were clearly minor figures by comparison.

[93] Offa seems to have attempted to increase the stability of Mercian kingship, both by the elimination of dynastic rivals to his son Ecgfrith, and the reduction in status of his subject kings, sometimes to the rank of ealdorman.

[95] There is evidence that Offa constructed a series of defensive burhs, or fortified towns; the locations are not generally agreed on but may include Bedford, Hereford, Northampton, Oxford and Stamford.

In addition to their defensive uses, these burhs are thought to have been administrative centres, serving as regional markets and indicating a transformation of the Mercian economy away from its origins as a grouping of midland peoples.

[11] In 749, Æthelbald of Mercia had issued a charter that freed ecclesiastical lands from all obligations except the requirement to build forts and bridges—obligations which lay upon everyone, as part of the trinoda necessitas.

[106] The reform in the coinage appears to have extended beyond Offa's own mints: the kings of East Anglia, Kent and Wessex all produced coins of the new heavier weight in this period.

"[1] It is now believed that Offa thought of himself as "King of the Mercians", and that his military successes were part of the transformation of Mercia from an overlordship of midland peoples into a powerful and aggressive kingdom.

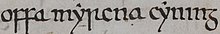

[129][130] In 1837 a Saxon coffin was unearthed in the graveyard of St Mary's Church, Hemel Hempstead which bore an inscription that it held the "ashes of King Offa of the Mercians".

[132] A letter written by Alcuin in 797 to a Mercian ealdorman named Osbert makes it apparent that Offa had gone to great lengths to ensure that his son Ecgfrith would succeed him.