The King and I

A hit West End London run and U.S. national tour followed, together with the 1956 film for which Brynner won the Academy Award for Best Actor, and the musical was recorded several times.

Her additional request, to live in or near the missionary community to ensure she was not deprived of Western company, aroused suspicion in Mongkut, who cautioned in a letter, "we need not have teacher of Christianity as they are abundant here".

[4] Leonowens and Louis temporarily lived as guests of Mongkut's prime minister, and after the first house offered was found to be unsuitable, the family moved into a brick residence (wooden structures decayed quickly in Bangkok's climate) within walking distance of the palace.

[13][14] Rodgers and Hammerstein could see no coherent story from which a musical could be made[13] until they saw the 1946 film adaptation, starring Irene Dunne and Rex Harrison, and how the screenplay united the episodes in the novel.

[16] For her part, Lawrence committed to remaining in the show until June 1, 1953, and waived the star's usual veto rights over cast and director, leaving control in the hands of the two authors.

He first thought that Anna would simply tell the wives something about her past, and wrote such lyrics as "I was dazzled by the splendor/Of Calcutta and Bombay" and "The celebrities were many/And the parties very gay/(I recall a curry dinner/And a certain Major Grey).

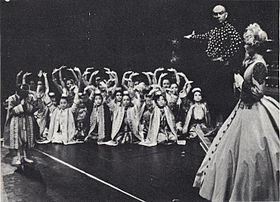

The costume designer, Sharaff, wryly pointed the press to the incongruity of a Victorian British governess in the midst of an exotic court: "The first-act finale of The King and I will feature Miss Lawrence, Mr. Brynner, and a pink satin ball gown.

The Variety critic noted that despite her recent illness she "slinks, acts, cavorts, and in general exhibits exceedingly well her several facets for entertaining", but the Philadelphia Bulletin printed that her "already thin voice is now starting to wear a great deal thinner".

Even the weather cooperated: heavy rain in New York stopped in time to allow the mostly wealthy or connected opening night audience to arrive dry at the St. James Theatre.

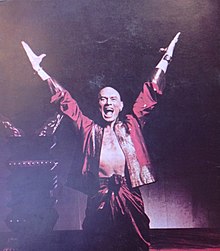

[92] In early 1976, Brynner received an offer from impresarios Lee Gruber and Shelly Gross to star, in the role that he had created 25 years before, in a U.S. national tour and Broadway revival.

[108] On September 13, 1983, in Los Angeles, Brynner celebrated his 4,000th performance as the King; on the same day he was privately diagnosed with inoperable lung cancer, and the tour had to shut down for a few months while he received painful radiation therapy to shrink the tumor.

[104] From August 1989 to March 1990, Rudolf Nureyev played the King in a North American tour opposite Liz Robertson, with Kermoyan as the Kralahome, directed by Arthur Storch and with the original Robbins choreography.

[114] Reviews were uniformly critical, lamenting that Nureyev failed to embody the character, "a King who stands around like a sulky teenager who didn't ask to be invited to this party.

[122] The production was praised for "lavish ... sumptuous" designs by Roger Kirk (costumes) and Brian Thomson (sets), who both won Tony[56] and Drama Desk Awards for their work.

"[143] In April 2016, this production transferred to Lyric Opera of Chicago featuring Kate Baldwin as Anna, Paolo Montalban as the King and Ali Ewoldt and was enthusiastically received by the critics.

[146] Some critics questioned anew the portrayal of the Siamese court as barbaric and asked why a show where "the laughs come from the Thai people mis-understanding British ... culture" should be selected for revival.

[148][149] Reviews were uniformly glowing, with Ben Brantley of The New York Times calling it a "resplendent production", praising the cast (especially O'Hara), direction, choreographer, designs and orchestra, and commenting that Sher "sheds a light [on the vintage material] that isn't harsh or misty but clarifying [and] balances epic sweep with intimate sensibility.

[158] A tour of the Lincoln Center production began in February 2023 in the U.K. and Ireland, directed by Sher, choreographed by Gattelli and starring Darren Lee as the King and Helen George as Anna.

Samantha Eggar played "Anna Owens", with Brian Tochi as Chulalongkorn, Keye Luke as the Kralahome, Eric Shea as Louis, Lisa Lu as Lady Thiang, and Rosalind Chao as Princess Serena.

This is exhibited in the piercing major seconds that frame "A Puzzlement", the flute melody in "We Kiss in a Shadow", open fifths, the exotic 6/2 chords that shape "My Lord and Master", and in some of the incidental music.

"[176] According to Rodgers' biographer William Hyland, the score for The King and I is much more closely tied to the action than that of South Pacific, "which had its share of purely entertaining songs".

[177] For example, the opening song, "I Whistle a Happy Tune", establishes Anna's fear upon entering a strange land with her small son, but the merry melody also expresses her determination to keep a stiff upper lip.

He judges it to be Brynner's best performance, calling Towers "great" and Martin Vidnovic, June Angela and the rest of the supporting cast "fabulous", though lamenting the omission of the ballet.

[178][182] Kenrick praises the performance of both stars on the 1996 Broadway revival recording, calling Lou Diamond Phillips "that rarity, a King who can stand free of Brynner's shadow".

[178] Hischak finds the soundtrack to the 1999 animated film with Christiane Noll as Anna and Martin Vidnovic as the King, as well as Barbra Streisand singing on one track, more enjoyable than the movie itself,[180] but Kenrick writes that his sole use for that CD is as a coaster.

"[183] Barely less enthusiastic was John Lardner in The New Yorker, who wrote, "Even those of us who find [the Rodgers and Hammerstein musicals] a little too unremittingly wholesome are bound to take pleasure in the high spirits and technical skill that their authors, and producers, have put into them.

[187] In 1963, New York Times reviewer Lewis Funke said of the musical, "Mr. Hammerstein put all of his big heart into the simple story of a British woman's adventures, heartaches, and triumphs. ...

"[190] Critic Richard Christiansen in the Chicago Tribune observed, of a 1998 tour stop at the Auditorium Theatre: "Written in a more leisurely and innocent and less politically correct period, [The King and I] cannot escape the 1990s onus of its condescending attitude toward the pidgin English monarch and his people.

"[191] When the production reached London in 2000, however, it received uniformly positive reviews; the Financial Times called it "a handsome, spectacular, strongly performed introduction to one of the truly great musicals".

[194] Other commentators, however, such as composer Mohammed Fairouz, argued that an attempt at sensitivity in production cannot compensate for "the inaccurate portrayal of the historic King Mongkut as a childlike tyrant and the infantilization of the entire Siamese population of the court", which demonstrate a racist subtext in the piece, even in 1951 when it was written.