Kingsley Plantation

[4] Evidence of pre-Columbian Timucua life is on the island, as are the remains of a Spanish mission named San Juan del Puerto.

Under British rule in 1765, a plantation was established that cycled through several owners while Florida was transferred back to Spain and then the United States.

The longest span of ownership was under Kingsley and his family, a polygamous and multiracial household controlled by and resistant to the issues of race and slavery.

Zephaniah Kingsley wrote a defense of slavery and the three-tier social system that acknowledged the rights of free people of color that existed in Florida under Spanish rule.

"At the other end of Fort George, now Batten Island, he built himself a house of some size, which is now [1878] in ruins; there lived Flora, his black mistress.

"[7]: 845 "In the 1830 census he owned only 39 slaves at the present Fort George site, but 188 at a little-known San José plantation, in Nassau County.

[3]: 69 In 1836 he moved his entire family from Florida, since Kingsley's free Blacks were ever more unwelcome and insecure, to a plantation called Mayorasgo de Koka, at the time in Haiti but from the 1840s in the Dominican Republic.

[9] The north Atlantic coast of Florida had been inhabited for approximately 12,000 years when Spanish explorer Juan Ponce de León landed near Cape Canaveral in 1513.

An estimated 35 chiefdoms existed in the territory,[10] and their societies were complex with large villages sustained by fishing, hunting, and agriculture, but they frequently warred with each other and unrelated groups of Native Americans.

Spanish settlers had established missions—including one on Fort George Island named San Juan del Puerto that eventually gave the nearby St. Johns River its name—but their frequent battles with the Timucua and a decline in mission activity curbed development.

Richard Hazard owned the first plantation on Fort George Island in 1765, harvesting indigo with several dozen enslaved Africans.

McQueen settled with 300 slaves and constructed a large house in a unique architectural style exhibiting four corner pavilions surrounding a great room.

[16] Born in Bristol, England and educated in London after his family moved to colonial South Carolina, Zephaniah Kingsley (1765–1843) established his career as a slave trader and shipping magnate, which allowed him to travel widely.

Kingsley owned several plantations around the lower St. Johns River in what is today Jacksonville, and Drayton Island in central Florida; two of them may have been managed part-time by his wife, a former slave named Anna Madgigine Jai (1793–1870).

Historian Daniel Schafer posits that Anna Jai would have been familiar with the concepts of polygamy and marrying a slave master to acquire one's freedom.

"[26] In 1823 President James Monroe appointed Kingsley to Florida's Territorial Council, where he tried to persuade them to define the rights of free people of color.

[citation needed] The Florida Territorial Council passed laws that forbade interracial marriage and the inheriting of property by free blacks or mixed race descendants.

To avoid difficulties with the new government in what he termed its "spirit of intolerant prejudice", Kingsley sent his wives, children, and a few slaves to Haiti, by that time a free black republic.

The Ribault Club, built in 1928 and restored in 2003, is on the National Register of Historic Sites and is today run by the state of Florida as the Visitor Center for Fort George Island.

[43]: 74–75 To increase their value and salability, newly-arrived slaves were taught some English and trained in agricultural tasks, and then they were marketed at premium prices to planters.

Archeologist Charles H. Fairbanks received a Florida Park Service grant to study artifacts found at the slave quarters.

His findings, published in 1968, initiated further interest and research in African-American archeology in the U.S.[49] Concentrating on two particular cabins bordering on Palmetto Avenue, Fairbanks found cooking pots used in fireplaces, animal bones—fish, pigs, raccoons, and turtles—discarded as food byproducts, and musket balls and fishing weights.

Kingsley himself wrote about not interfering in his slaves' family lives and "encouraged as much as possible dancing, merriment and dress, for which Saturday afternoon and night, and Sunday morning were dedicated.

[55] In the construction of tabby buildings at the Kingsley Plantation on Fort George Island, Florida, ...wooden or metal boxes with handles, that varied from twelve to thirty-six inches in height [0.3 – 0.9 m], were devised to take the place of forms which had to be dismantled and reassembled for each level.

The twenty-four tabby slave houses at the Kingsley Plantation represented a massive construction effort which attests to the apparent success of this innovation.

The material made the houses remarkably durable, resistant to weather and insects, better insulated than wood, and the ingredients were accessible and cheap, although labor-intensive.

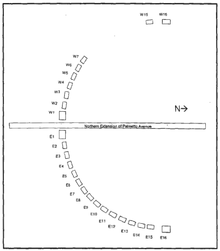

The arrangement of the quarters is distinctive: there were originally 32 cabins laid out in a semicircular arc interrupted by the main thoroughfare to the plantation, Palmetto Avenue.

In one cabin an intact sacrificed chicken on top of an egg was unearthed, adding evidence to the hypothesis that African slaves kept many of their traditions alive in North America.

The house—resembling 17th-century British gentry homes[58]—has a large center room and four one-story pavilions at each corner that allowed air to circulate through them to keep them cooler in the summer; each was a bedroom that had a fireplace to heat more efficiently in the winter.

[6] The main house protected John McQueen's family and neighbors during attacks from invading Creeks in 1802; he wrote that at one time 26 people took refuge there.