Japanese calendar

[1] The written form starts with the year, then the month and finally the day, coinciding with the ISO 8601 standard.

The lunisolar Chinese calendar was introduced to Japan via Korea in the middle of the sixth century.

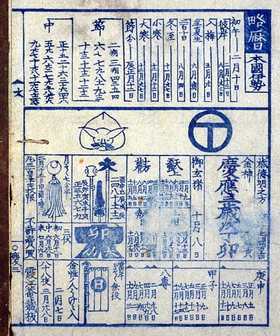

[3][4] Its sexagenary cycle was often used together with era names, as in the 1729 Ise calendar shown above, which is for "the 14th year of Kyōhō, tsuchi-no-to no tori", i.e., 己酉.

However, its influence can still be felt in the idea of "lucky and unlucky days" (described below), the traditional meanings behind the name of each month, and other features of modern Japanese calendars.

[8][9][10] The name of the new era was announced by the Japanese government on 1 April 2019, a month prior to Naruhito's accession to the throne.

[11][12][10] The previous era, Heisei, came to an end on 30 April 2019, after Japan's former emperor, Akihito, abdicated the throne.

[13][8][14] The Japanese imperial year (皇紀 (kōki) or 紀元 (kigen)) is based on the date of the legendary founding of Japan by Emperor Jimmu in 660 BC.

The 1940 Summer Olympics and Tokyo Expo were planned as anniversary events, but were canceled due to the Second Sino-Japanese War.

[17] Usage of kōki dating can be a nationalist signal, pointing out that the history of Japan's imperial family is longer than that of Christianity, the basis of the Anno Domini (AD) system.

The Western Common Era (Anno Domini) (西暦, seireki) system, based on the solar Gregorian calendar, was first introduced in 1873 as part of the Japan's Meiji period modernization.

This system was adapted from the Chinese in 1685 by court astronomer Shibukawa Shunkai, rewriting the names to better match the local climate and nature in his native Japan.

[20][21] Each kō has traditional customs, festivals, foods, flowers and birds associated with it:[22][23] Zassetsu (雑節) is a collective term for special seasonal days within the 24 sekki.

The "traditional names" for each month, shown below, are still used by some in fields such as poetry; of the twelve, Shiwasu is still widely used today.

The opening paragraph of a letter or the greeting in a speech might borrow one of these names to convey a sense of the season.

The seven-day week, with names for the days corresponding to the Latin system, was brought to Japan around AD 800 with the Buddhist calendar.

Many Japanese retailers do not close on Saturdays or Sundays, because many office workers and their families are expected to visit the shops during the weekend.

The rokuyō are commonly found on Japanese calendars and are often used to plan weddings and funerals, though most people ignore them in ordinary life.

After World War II, the names of Japanese national holidays were completely changed because of the secular state principle (Article 20, The Constitution of Japan).

The sekku were made official holidays during Edo period on Chinese lunisolar calendar.

Not sekku: In contrast to other East Asian countries such as China, Vietnam, Korea and Mongolia, Japan has almost completely forgotten the Chinese calendar.

But this system often brings a strong seasonal sense of gap since the event is 3 to 7 weeks earlier than in the traditional calendar.

Modern Japanese culture has invented a kind of "compromised" way of setting dates for festivals called Tsuki-okure ("One-Month Delay") or Chūreki ("The Eclectic Calendar").

Although this is just de facto and customary, it is broadly used when setting the dates of many folklore events and religious festivals.